Solipsism. It’s a fancy word that means that the self is the only existing reality and that the external world, including other people, are representations of one’s own self and can have no independent existence. A person who follows this philosophy may believe that others see the world as he does and will behave as he would.

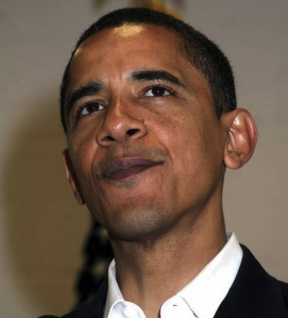

It’s a quality often found in narcissists, people who greatly admire themselves — such as a presidential candidate confident that he is a better speechwriter than his speechwriters, knows more about policy than his policy directors and is a better political director than his political director.

If that sounds familiar, it’s a paraphrase of what President Obama told top political aide Patrick Gaspard in 2008, according to the New Yorker’s Ryan Lizza.

More recently, Obama’s narcissism has been painfully apparent as the United States suffers one reversal after another in world affairs. But it has been apparent ever since he started running for president in 2007.

Candidate Obama campaigned not just as a critic of the policies of the opposing party’s president, as many candidates do, but he portrayed himself repeatedly as someone who, because he “looks different” from other presidents, would make America beloved and cherished in the world.

Plenty of solipsism here. Obama’s status as the possible — and then actual — first black president was surely an electoral asset. Most Americans believed and believe that, given the nation’s history, the election of a black president would be a good thing, at least in the abstract.

But that history has less resonance beyond America’s borders. Obama must have been surprised to find, on his trip to his father’s native Africa, that he was less popular there than George W. Bush, thanks to Bush’s program to combat AIDS.

Obama was also mistaken in thinking that his election and the departure of the cowboy bully Bush would make the United States popular again among the world’s leaders and peoples — though it had that effect in the faculty lounges and university neighborhoods Obama had chosen to inhabit.

In the wider world, the United States, as the largest and mightiest power, is bound to be resented and blamed for every unwelcome development. American presidents for more than a century have been characterized as crude and bumptious by foreign elites.

Moreover, as Robert Gates argued persuasively in his 1996 and 2014 memoirs, there is more continuity in American foreign policy than domestic campaign rhetoric suggests. From Guantanamo to Afghanistan, Obama found himself obliged more to carry on than to repudiate Bush’s policies.

Where he has clearly changed course, he has done so solipsistically. A reset with Russia was possible, he reasoned, because Vladimir Putin, insulted by Bush’s mulishness, was ready to cooperate with a president in mutually advantageous win-win agreements.

So in the past week, Obama has insisted that Putin’s invasion of Ukraine’s Crimea was not in his own interest. No doubt most in the faculty lounge would see it that way. But Putin clearly doesn’t. As the military say, the enemy has a vote.

And in his astonishing interview last week with Bloomberg’s Jeffrey Goldberg, Obama declared that Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas was ready to accept peace with Israel. Again, that’s what Obama and the faculty lounge would do. But Abbas has turned down one generous peace deal and has never said he would recognize Israel as a Jewish state.

Obama’s assumption that other leaders share his views has its limits. It does not always apply to those who have been allies and friends of the United States.

In the Goldberg interview, he lashed Israel, and by implication Benjamin Netanyahu, for “aggressive settlement construction” in the West Bank. The implication is that only Israel is blocking a peace agreement. But it was Abbas who has rejected John Kerry’s framework.

Obama’s solipsistic narcissism extends even to the mullahs of Iran. This goes back again to the 2008 campaign:

The problem was Bush’s refusal to negotiate. Speak emolliently, send greetings on Muslim holidays and ignore the Green Movement protesters, and Iranian leaders would see that it is in their interest to halt their nuclear weapons program.

Most Americans, conservative as well as liberal, would be delighted if Putin, the Palestinians and Ayatollah Khamenei believed and behaved as we would. They would be pleased to see an enlightened American leader bridge rhetorical differences and reach accommodations that left all sides content and at peace.

That, unhappily, is not the world we live in. Being on the lookout for common ground is sensible. Assuming common ground when none exists is foolish. And often has bad consequences.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Michael Barone is Senior Political Analyst for the Washington Examiner, and co-author of The Almanac of American Politics.