by Rick Hampson • USAToday

by Rick Hampson • USAToday

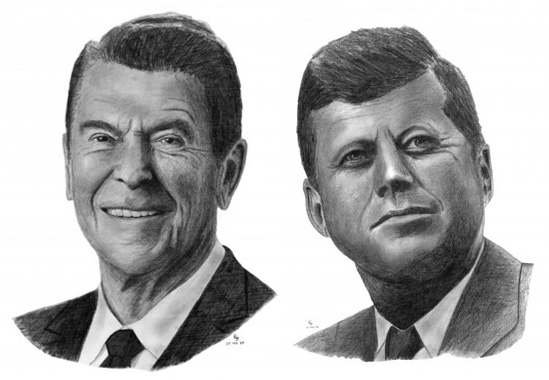

“Ich bin ein Berliner,” John F. Kennedy proclaimed in 1963. Of communism’s defenders, he roared, “Let them come to Berlin!”

Standing at the communist barrier dividing the same city 24 years later, Ronald Reagan cried, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

The 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall on Nov. 9 raises a nostalgic question: Whatever happened to the kind of inspirational presidential oratory that helped bring down that wall — and Soviet communism?

In the history of the American presidency, such triumphs are few and fragile. Even those great Berlin lines might not have been delivered.

Kennedy’s famous words were not in the final draft of his prepared text. The signature line in Reagan’s speech was strenuously resisted by senior advisers., and it didn’t make a big impression at the time.

Today, when President Obama’s rhetoric seems unable to stop aggression in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, the two Berlin speeches demonstrate the power of words to influence world affairs, as well as their limits.

The speeches also illustrate how hard it is for any president to find the right words and how crucial context is to their impact.

The Kennedy and Reagan speeches defined the Berlin Wall. The first speech helped make it an international symbol of political oppression. The second arguably helped bring it down.

Each speech was a tightrope walk. On one level, Kennedy and Reagan acted like passionate Cold Warriors. Kennedy went off script and Reagan uncharacteristically shouted his most provocative line.

But both men were at stages in their presidency when they were trying to improve relations with the Soviet Union. Kennedy wanted to ease tensions aroused by the Cuban missile crisis a year earlier. Reagan was building a relationship with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev based on the latter’s embrace of glasnost — openness.

Both presidents offered a vision of a world beyond communism. Kenneth Duberstein, White House deputy chief of staff in 1987, says that after Reagan’s speech, “it was inevitable the wall would come down.”

Historians say the speeches were not as pivotal as many Americans believe. Soviet communism continued after Kennedy’s speech for a quarter-century – a third of its lifetime – and the wall didn’t fall as a direct result of Reagan’s speech two years earlier.

Mary Elise Sarotte, author of The Collapse, a new book on the wall, describes its end as an explosion with a powder keg and a spark. Those behind the Iron Curtain deserve credit for lighting the spark in 1989, she says. Kennedy and Reagan, years earlier, provided some of the powder.

Kennedy: June 26, 1963

The first thing to understand about John Kennedy and the Berlin Wall is that he virtually acquiesced to its construction.

When World War II ended, the Americans, British, French and Soviets had split Germany — and the capital city of Berlin — into four occupation zones. As the Cold War developed between the Soviets and the other powers, the first three zones became West Germany, and West Berlin became a democratic, capitalist island inside Soviet-dominated East Germany.

In 1961, as a thousand East Germans a day migrated to West Berlin, the communist East German regime erected a barrier almost overnight to stem the flow.

Washington did no more than protest. “A wall is a hell of a lot better than a war,” Kennedy said. He couldn’t get rid of the wall, but two years later, on a visit to Berlin, he used it.

He faced an adoring crowd of more than 400,000. Although he spoke 2 miles from the wall, he’d seen it earlier in the day, and when he began to speak, he sounded angry.

Although Kennedy’s speech was typed on the index cards he carried in his suit coat pocket, the typescript did not include almost half the speech he actually gave. The cards did bear his handwritten phonetic pronunciations for the German phrases he’d practiced.

“Two thousand years ago,” he began, “the proudest boast was Civis Romanus sum. (I am a citizen of Rome.) Today, in the world of freedom, the proudest boast is ‘Ich bin ein Berliner.”‘

The crowd roared. Kennedy, delighted, continued: “There are many people in the world who really don’t understand, or say they don’t, what is the great issue between the free world and the communist world. … Let them come to Berlin!”

He continued to invoke that refrain, ending with “Lass’ sie nach Berlin kommen! Let them come to Berlin!” The crowd chanted, “KEN-NE-DY!”

He closed minutes later by returning where he’d started: “All free men, wherever they live, are citizens of Berlin. And therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words ‘Ich bin ein Berliner!’ ” Pandemonium.

Afterward, presidential adviser McGeorge Bundy told the president the speech “went a little too far.” JFK seemed to agree, and they edited the text of his next speech that day to make it more conciliatory.

That night, Air Force One flew toward Ireland for a visit to JFK’s ancestral homeland. “We’ll never have a day like this as long as we live,” he told an aide. Less than five months later, he was dead.

Reagan: June 12, 1987

After White House speechwriter Peter Robinson was assigned to draft Reagan’s address for the president’s visit to Berlin in 1987, he visited the city to gather material.

He sat down with a senior U.S. diplomat, who Robinson says focused on what Reagan should not say. That meant anything that might provoke the Soviets. Above all, the man said, don’t raise false hopes about the wall – West Berliners had gotten used to it; it wasn’t an issue any more.

That night, at a dinner party with some Berliners, Robinson says he tested the diplomat’s conventional wisdom: “Have you gotten used to the wall?”

He says the conversation stopped. Finally, one man spoke up. He had not seen his sister in decades, even though she lived 20 miles away, in East Berlin. “Do you think I can get used to that?” he asked.

Then the hostess, Inge Elz, helped make history: Face red, fist pounding into her palm, she said that if Gorbachev was serious about reforming communism and reaching out to the West, “he can prove it. He can get rid of this wall.”

That, Robinson thought, sounds like Reagan.

Back at the White House, Robinson plowed through drafts of the speech. In one, Reagan addresses “Herr Gorbachev.” In another, he says “bring down this wall.” In a third, the “tear down” line is delivered in German.

After Robinson’s final draft went to the president, he met with Reagan in the Oval Office. The president said he liked the speech. Robinson pressed him. What did he want people east of the wall — maybe as far as Moscow — to hear?

That line about tearing down the wall, Reagan replied.

Others, including White House Chief of Staff Howard Baker, Secretary of State George Schultz and national security adviser Colin Powell, disagreed. Their reasoning: While Gorbachev was trying to ease Cold War tensions, a bellicose speech would play into the hands of Kremlin hard-liners.

The State Department sent Reagan seven drafts, none of which asked anyone to tear down anything.

Finally, Ken Duberstein took up the issue with Reagan in Venice, where he was attending an economic summit before going to Berlin. The deputy chief of staff outlined the objections. “But you’re the president,” he says he added. “You get to decide.”

An hour later, Reagan had: “We’ll leave it in.”

The next day, on the limousine ride to the speech, Reagan read aloud through his text. When he got to the offending line, Duberstein recalls, Reagan grinned and said, “The boys at State are going to kill me, but it’s the right thing to do.”

The timing was not auspicious. Many Germans opposed a plan to install U.S. short-range missiles in Europe, and West Berlin — generally to the political left of the rest of the country — wasn’t sympathetic to the conservative Reagan.

Reagan spoke 100 yards from the wall, bulletproof glass at his back. He said later that he saw East German police pushing people away from loudspeakers to prevent them from hearing his speech.

Reagan wrote in his autobiography that “I felt an anger well up in me, and I’m sure the anger was reflected in my voice when I said those words.”

“Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization — come here to this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate! Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

Reaction to the speech was muted. In Germany, “we were puzzled,” recalls Andreas Daum, the historian who wrote Kennedy in Berlin. “Was it a sound bite from the Cold War? The speech just sort of hung in the air.”

Gorbachev said later, “We were not impressed. We knew Mr. Reagan’s original profession was actor.”

But two years later, after the wall fell, the clip of Reagan’s line was everywhere.

The Power of Words

Presidential orators (and their speechwriters) work in the shadow of Kennedy and Reagan in Berlin.

“They articulated a plausible vision of the world as how it could be, other than the way it was,” Robinson says. “When was the last time a president did that?”