by Peter Roff • The Hill

A debate has raged for more than 20 years now over the best way to bend the U.S. healthcare cost curve downward. So far, no one is winning – least of all patients and healthcare providers. And no one will as long as “bending the curve” (which is just a fancy way of saying we need to find ways to make the delivery of healthcare cheaper) remains the primary objective regardless of the impact on patient care.

A debate has raged for more than 20 years now over the best way to bend the U.S. healthcare cost curve downward. So far, no one is winning – least of all patients and healthcare providers. And no one will as long as “bending the curve” (which is just a fancy way of saying we need to find ways to make the delivery of healthcare cheaper) remains the primary objective regardless of the impact on patient care.

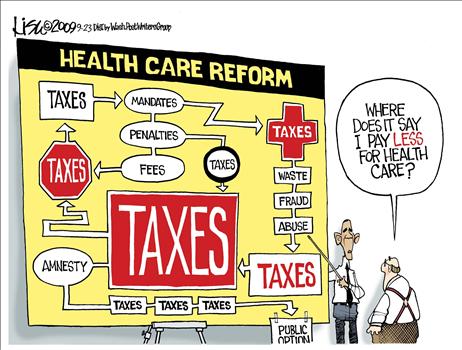

Up to now the debate has focused largely on what government can proactively do to ease costs. This led to the passage by the narrowest of margins of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act – which is really nothing more than a complex series of new regulations and taxes, fines and fees that have forced insurance companies, doctors, hospitals, and patients all to make changes in the way they provide and receive care as well as coverage.

People don’t like the new system very much but they weren’t exactly fans of the old one either. And no matter what the United States Supreme Court determines in the pending King vs. Burwell suit over the questionable use of tax dollars to subsidize health insurance bought through the federal exchange by people living in states that do not have exchanges of their own, things can probably only get worse.

The real solution, the one that policymakers should have been pursing right from the start, is to find ways to get government out of the healthcare business or, at least, to get it out of the way.

As former House Majority Leader Dick Armey (R-Texas) used to say, “Markets are rational. The government is not.” This is especially true in the healthcare sector where policy is determined by actuaries and accountants and ivory-tower researchers and health policy specialists. Real doctors, the kind that see patients and nurses hardly get into the room when decisions are made. This is how you get recommendations and policies leading to the rationing of care among the very sick, the very young, and the very old before too long. If the race is to make every healthcare dollar count for as much as possible, they lose.

The hospital is the nerve center of the healthcare system and, therefore, is the best place to start looking for economies that do not harm patient care. Thanks to the ACA, which is all about insurance and is really doing nothing to curtail costs while increasing the demand for care, independent hospitals in particular are being squeezed. They can no longer afford to do it all as they once did – unless they find partners. Sometimes that means mergers. And, according to federal law, that’s something that all too many times needs the affirmative approval of the U.S. government.

As public and private funding has been drastically hospitals have been forced to adapt. Hospital systems – a creative improvement on the old model of the independent community-based hospital — have proven they are better able to preserve access to care and emergency services and provide integrated and coordinated care while being able to revitalize poorly performing or inefficient hospitals.

Besides improving outcomes hospital systems are also, despite what their critics forecast, reducing the cost of care without depriving consumers of the benefits of market competition.

A recent study conducted by the Center for Healthcare Economics and Policy found that mergers and consolidation do not have a deleterious effect on patient access to care or commitment to public safety and community service. In fact the increase in the scale of operations made possible by the savings generated from the elimination of duplicated administrative costs actually improves the quality of care being provided while enhancing patient access.

The same study found there is no consistent statistical relationship between consolidation and hospital price increases. Arguments to the contrary are often based on outdated conclusions drawn from data assembled at a time when market conditions were very different. All of this, however, runs contrary to the dominant thinking among the regulators and analysts at the Federal Trade Commission, which must vote its approval for hospital mergers.

As it acts, the FTC actually harms people. That idea it knows better is contravened by the federal judge who found in FTC vs. St. Luke’s Health System that the best result for the community would be to allow hospitals and doctors to join together when the government wanted to block the combination of forces and facilities.

So now we have the U.S. government, in this case the FTC is standing in the way of progress toward to more efficient and effective health care system by failing to acknowledge the world has changed and that hospitals that cannot change with it will fail.

A closed hospital helps no one. The market can address these issues better than the government, which is why the FTC needs to get out of the way. Enforcement actions convened to impress appropriators on Capitol Hill do little to improve the quality of America’s healthcare. Regulators who overlook the ability of hospitals and doctors and nurses to work together to build a more comprehensive and efficient health care delivery system are doing no one any favors.