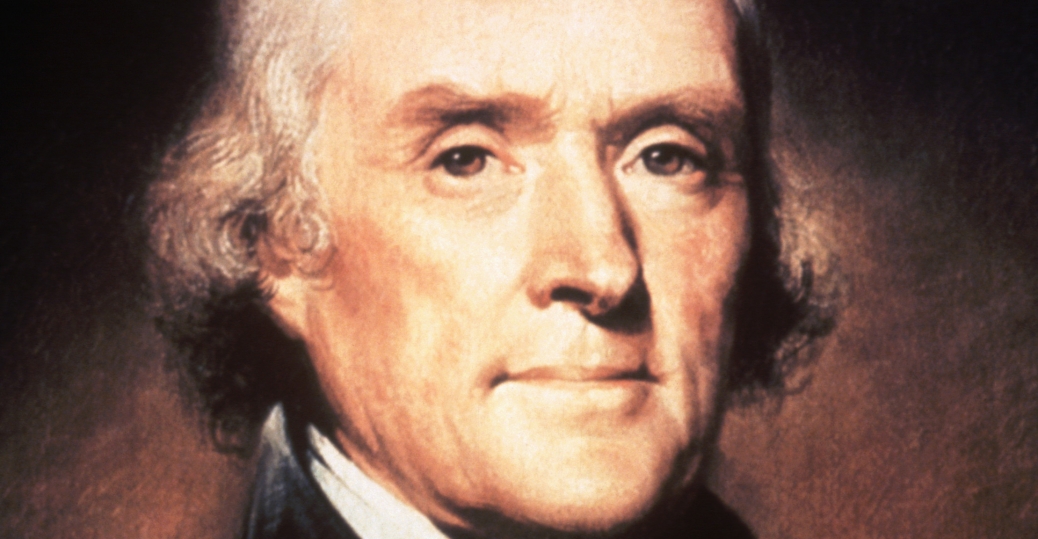

A couple weeks back we asked whether it might be time for the U.S. to start worrying about the International Criminal Court — an institution that not only sees few if any real limits on its power and has been stealthily circling American soldiers for some time now. Today, as a service to those seeking a solid philosophical/intellectual foundation for skepticism of this sort of uber-judicial overreach, at home or abroad, we present the following thoughts and insights courtesy American Founding Father and author the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson.

A couple weeks back we asked whether it might be time for the U.S. to start worrying about the International Criminal Court — an institution that not only sees few if any real limits on its power and has been stealthily circling American soldiers for some time now. Today, as a service to those seeking a solid philosophical/intellectual foundation for skepticism of this sort of uber-judicial overreach, at home or abroad, we present the following thoughts and insights courtesy American Founding Father and author the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson.

Obviously Jefferson’s critique is of a federal judiciary he worried would overstep its Constitutional bounds. Nevertheless, all of these arguments are more not less pertinent when discussing an aspiring transnational behemoth that seeks to place the entire planet under its uneven and politicized jurisdiction.

1. Judges Are Men, Not Angels, and, Thus, Susceptible to the Temptations of Power

“It is not enough that honest men are appointed judges. All know the influence of interest on the mind of man, and how unconsciously his judgment is warped by that influence. To this bias add that of the esprit de corps, of their peculiar maxim and creed that ‘it is the office of a good judge to enlarge his jurisdiction,’ and the absence of responsibility, and how can we expect impartial decision between the General government, of which they are themselves so eminent a part, and an individual state from which they have nothing to hope or fear?” — Autobiography, 1821.

2. Ever-Expanding Power and Reach Is the Enemy of Impartiality

“The great object of my fear is the Federal Judiciary. That body, like gravity, ever acting with noiseless foot and unalarming advance, gaining ground step by step and holding what it gains, is engulfing insidiously the special governments into the jaws of that which feeds them.” — Letter to Spencer Roane, 1821.

“The Judicial Branch must be independent of other branches of government, but not independent of the nation itself. It is rightly responsible to the people for irregular and censurable decisions…” — Letter to Archibald Stuart, 1791

“The judiciary of the United States is the subtle corps of sappers and miners constantly working under ground to undermine the foundations of our confederated fabric. They are construing our Constitution from a co-ordination of a general and special government to a general and supreme one alone. This will lay all things at their feet…” — Letter to Thomas Ritchie, 1820.

3. Ambiguous Jurisdiction Is an Invitation to Whim Worship and Tyranny

“Contrary to all correct example, [the Federal judiciary] are in the habit of going out of the question before them, to throw an anchor ahead and grapple further hold for future advances of power. They are then in fact the corps of sappers and miners, steadily working to undermine the independent rights of the States and to consolidate all power in the hands of that government in which they have so important a freehold estate.” — Autobiography, 1821.

4. When it Comes to Judicial Overlords, Less Is More

“Render the judiciary respectable by every means possible, to wit, firm tenure in office, competent salaries and reduction of their numbers.” — Letter to Archibald Stuart, 1791.

“It has long been my opinion, and I have never shrunk from its expression,… that the germ of dissolution of our Federal Government is in the constitution of the Federal Judiciary–an irresponsible body (for impeachment is scarcely a scare-crow), working like gravity by night and by day, gaining a little today and a little tomorrow, and advancing its noiseless step like a thief over the field of jurisdiction until all shall be usurped from the States and the government be consolidated into one. To this I am opposed.” — Letter to Charles Hammond, 1821.

5. To Keep Liberty Safe, Remember the Law Exists to Safeguard the Rights of the People, Not Aid the Domination Fantasies of Judges

“With us, all the branches of the government are elective by the people themselves, except the judiciary, of whose science and qualifications they are not competent judges. Yet, even in that department, we call in a jury of the people to decide all controverted matters of fact, because to that investigation they are entirely competent, leaving thus as little as possible, merely the law of the case, to the decision of the judges.” — Letter to A. Coray, 1823.