By Iain Murray • National Review Online

Anyone who studies the power bureaucrats have over ordinary Americans’ lives swiftly comes to the realization that the courts, which are meant to redress grievances, will be of little help. That’s because of a doctrine the Supreme Court adopted in the 1984 case Chevron USA Inc v. NRDC. The doctrine, known as Chevron Deference to those in the know, states that courts should usually defer to executive agencies when it comes to the interpretation of ambiguous statutes, of which there are many. A further doctrine, known as Auer after the case Auer v. Robbins, holds that courts should defer to agencies in how they interpret their own regulations.

Anyone who studies the power bureaucrats have over ordinary Americans’ lives swiftly comes to the realization that the courts, which are meant to redress grievances, will be of little help. That’s because of a doctrine the Supreme Court adopted in the 1984 case Chevron USA Inc v. NRDC. The doctrine, known as Chevron Deference to those in the know, states that courts should usually defer to executive agencies when it comes to the interpretation of ambiguous statutes, of which there are many. A further doctrine, known as Auer after the case Auer v. Robbins, holds that courts should defer to agencies in how they interpret their own regulations.

The rationale behind these decisions is well explained by Harvard’s Adrian Vermeule in a law review article published today on the subject of deference and due process. He points to the argument that “on grounds of both expertise and accountability, agencies are better positioned than courts to interpret governing statutes.” He also points to a growing body of case law incorporating Chevron principles and to the “Court’s recent emphatic pronouncement that Chevron may actually grant agencies the power to determine the scope of their own jurisdiction.”

This is all very well – courts may not want to get involved in incredibly detailed matters about which they have no specialized knowledge and where they would be likely to accept the argument of the executive in any case – but we are facing here a philosophical problem as much as a legal one. The British philosopher Sir Stuart Hampshire developed a concept of procedural justice that says that justice requires a “fair hearing” of grievances and a “just and fair weighting” of conflicting proposals and interpretations. As he put it, “Only the principle of fairness in settling conflicts can claim a universal ground as being a principle of shared rationality, indispensable in all decision making and in all intentional action.”

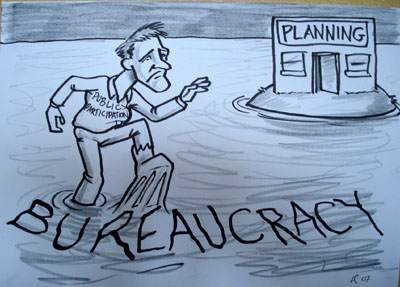

However convenient they may be for the Courts, the Chevron and Auer doctrines fail this basic test of fairness. There are other problems with them as well. The Heritage Foundation’s Elizabeth Slattery sums them up in this study from last year. They effectively create an unaccountable fourth branch of government, inured against review by outside parties beyond the occasional Congressional oversight hearing. The Courts have, if anything, reaffirmed these doctrines in recent decisions, and the late Justice Scalia was one of the architects and defenders of Chevron Deference. Any change in judicial doctrine may be a long time coming.

This is why a legislative solution is badly needed. Rep. John Ratcliffe (TX-04) has therefore introduced a bill, H.R. 4768, the Separation of Powers Restoration Act of 2016 (SOPRA), which amends the Administrative Procedure Act to direct courts to conduct a de novo review of all relevant questions of law, “including the interpretation of constitutional and statutory provisions and the provisions of agency rules.”

As Rep. Ratcliffe says,

“The constituents I represent aren’t just frustrated with the enormous quantity of regulations being rolled out by unelected federal bureaucrats – they’re fed up with the lack of accountability administrative agencies have when they make all these rules out of thin air.

“For too long, federal regulators have been allowed to run free and loose in their interpretation of the laws that Congress writes, resulting in a dangerous and unconstitutional culmination of power. The government works for the people – not the other way around – and I’m proud to help lead this effort to ensure the separation of powers is respected as our Founding Fathers intended.”

The bill will doubtless be looked one with dismay by judges and legal scholars, but it meets a basic philosophical need for fairness that our courts appear to have discarded in the name of expediency.