by Peter Roff • Townhall

Since coming to office South Korean President Moon Jae-in has moved quickly to put the past behind him. Politically, this is wise. His countrymen are tired of the byzantine games and corruption that for decades influenced the system of government and drove his predecessor from office.

His need to put his country’s house in order defies ideological concerns. He faces daunting security threats, especially from the North, but also a restless and dissatisfied people hungry for change. He leads an Asian tiger whose economic power is being challenged and which desperately needs to improve its trade relations with the West.

U.S. President Donald Trump is making the most of South Korea’s internal turmoil to bolster the U.S. efforts to exert its political and economic influence in Korea. Just a week before the special election that brought President Moon to power, Trump summed up the existing free trade agreement with South Korea as “horrible” and vowed to renegotiate the pact.

Given Trump’s decision to withdraw the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership Act, Korea must understand this threat to the FTA is not a bluff. In a letter on Wednesday, the administration called South Korea “an important ally and key trading partner” but said it “had real concerns about our significant trade imbalance”.

“We can and must do better,” US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer said in a statement. The US trade deficit for goods and services with Korea was about $17 billion in 2016 although service exports produced a pro-U.S. surplus. Between them the two countries exchanged about $145 billion in 2016.

The apparent disarray in the country’s corporate institutions works to America’s advantage. The indictment of Lee Jae-yong, the heir apparent of the massive conglomerate Samsung, has created uncertainty about the terms and conditions about future bilateral commercial ties. Lee’s indictment focuses on $37 million Samsung paid to associates of Choi Soon-sil, a confidant of the deposed president that Samsung does not deny making payments but contends was not for political favors.

All this feeds Trump’s skepticism about what the U.S might gain through deeper and stronger trade ties now. Moon must deal the corruption. Park Geun-hye’s impeachment served as an unhelpful reminder of South Korea’s reputation as a place where high-level political corruption was the order of the day ever since the rein of her father, Park Chung–he, who built what came to be called “Korea Inc.” and ruled with an iron fist in the 1960s and 1970s.

At the same time, Moon’s election was still a referendum on the future not just an effort to re-litigate the past. The short but spirited campaign brought to the surface generational and economic divisions in the country. A recent Gallup poll found lopsided support for Moon among Koreans under the age of 30 and a proportionately strong support for conservative candidates among voters 60 and older. Younger Koreans are concerned about perceived shrinking economic opportunities and growing income gaps.

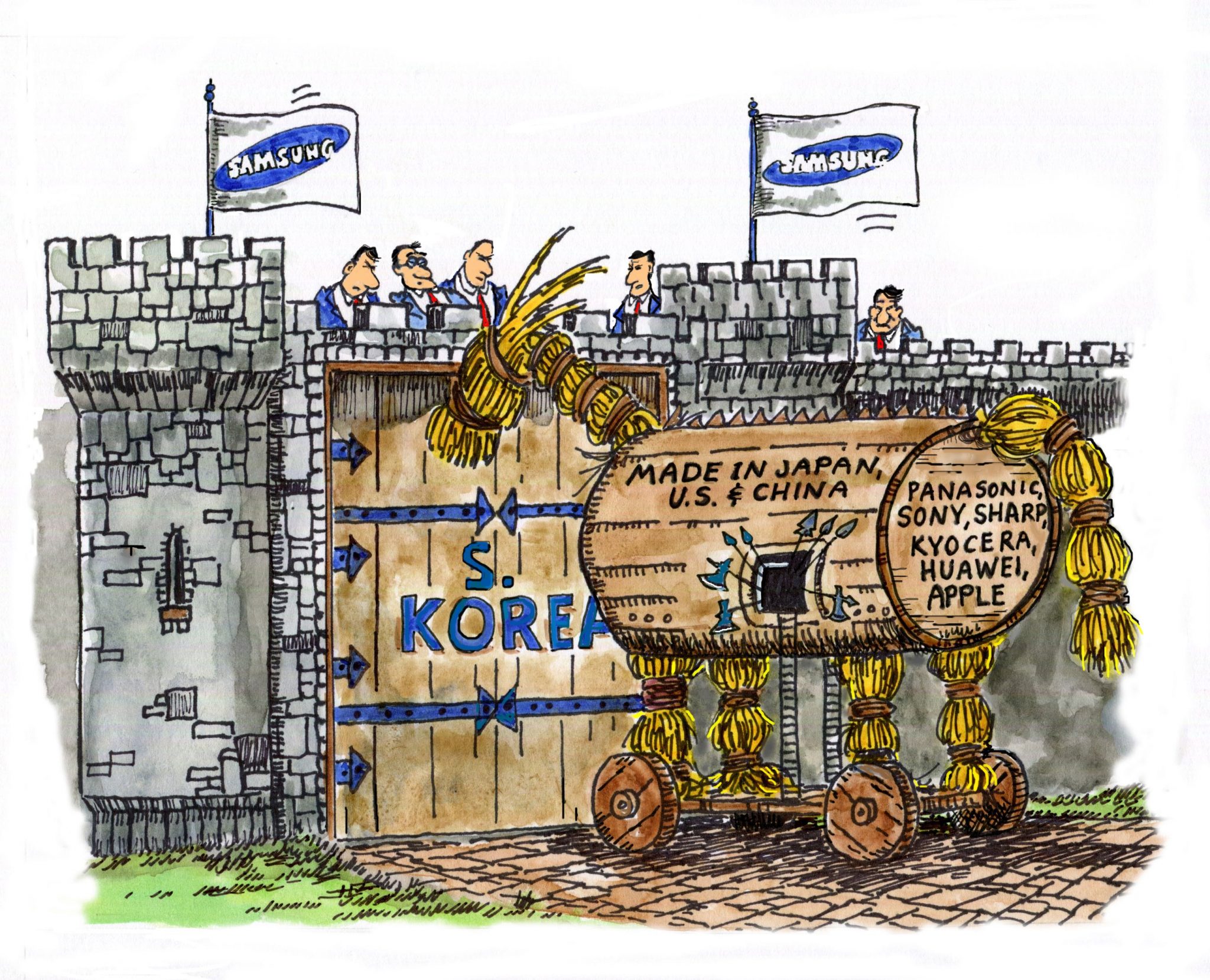

While taking on alleged corruption at the upper echelons at Samsung could allow Moon to demonstrate his bona fides as a reformer the pending legal case should be addressed on its merits alone. It is not a political matter and the government should move on. The residuals of the scandal and imprisonment of Samsung’s de facto chairman threaten to weaken Samsung for years to come as it deals with leadership uncertainty and the resulting loss in productivity. This is a problem for the Korean people and a potential boon to U.S. trade interests. Samsung is one Korea’s “chaebols” – powerful conglomerates run by families that effectively control the nation’s economy. Samsung alone, with its sprawling interests in electronics, shipbuilding, insurance, construction, medicine and more, is estimated to account for around 15 percent of South Korea’s entire economy. Some estimate the company accounts for a fifth of the country’s GDP.

These companies have helped fuel South Korea’s extraordinary growth chronicled in a new book by Michael Breen aptly titled, “The New Koreans.” The book notes that in the aftermath of World War II, Korea’s per capita income was at the same level of Sudan. Thanks to Park Chung-hee’s “guided capitalism” in the 1960s and the rise of today’s chaebols, South Korea is the world’s 13th largest economy and stands with only Taiwan as having managed annual economic growth of five percent for five decades in a row. A makeover at one of the country’s corporate powerhouses could put that streak in jeopardy.

A central tenet of Trump’s critique of the U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement specifically and U.S. trade policy in general is such agreements had favored narrow economic interests or broad geopolitical aims rather than the economic well-being of the average American worker. Given the connection between the chaebols and Korea’s economic strength, the Trump Administration will be operating from a much stronger negotiating position as companies like Samsung struggle in the new Korea.

The unprecedented menacing by Kim Jong-un in the North creates an imperative for both countries to assess more grave and urgent threats. While Moon and Trump diverge on how to handle the threat for now, they must find common ground. More than ever, South Koreans need to move past divisions and scandals and stand unified in confronting a range of economic and security threats.