By Chuck DeVore • The Federalist

A California lawmaker recently came up with the bright idea that waiters who serve unrequested straws should go to jail for six months because … the environment. Another duo of lawmakers have proposed more than doubling California’s business tax under the theory that employers wouldn’t miss the cash, because the tax increase would only take about half of President Trump’s recent tax cut.

Lawmakers all over the nation introduce weird or controversial legislation. Most of these bills are harmless, as they’d never make it out of the legislature, much less be signed into law by a governor. In California, however, many such legislative proposals are taken seriously and often do get signed into law.

Why is this? Sure, California is a liberal state. But, one key governmental structural factor likely contributes to Golden State lawmakers’ seeming isolation from common sense: California lawmakers often make a career of full-time politics.

A century ago, California was at the vanguard of the Progressive Era. Featuring politicians of both major parties, progressives then, as now, saw government a prime driver of change. Further, they believed that politicians, at the most, should only provide guidance to highly trained bureaucrats who would then honestly and efficiently run government.

The 1966 Ballot Initiative

By 1966 the progressive concept of professional government made it to the California state legislature when a ballot initiative — another progressive innovation — passed, ending California’s part-time legislature.

I served in California’s “professional” full-time legislature for six years before moving to Texas in 2011. Since then, I’ve worked with the Texas legislature while at the Texas Public Policy Foundation. That experience led to my curiosity over the professional backgrounds of the lawmakers in the two most-populous states.

In contrast to California, Texas still has a citizen legislature that meets every other year for 140 days with the occasional special session. Texas lawmakers earn a salary of $7,200 annually. Rank and file California legislators earn $107,240.

In 2012 I reviewed the biographies of all 301 state lawmakers in California and Texas, writing in the National Review:

… only 18 percent of the Democrats who control both houses of California’s full-time legislature worked in business or medicine before being elected. The remainder drew paychecks from government, worked as community organizers, or were attorneys.

In Texas, with its part-time legislature, 75 percent of the Republicans who control both houses earn a living in business, farming, or medicine, with 19 percent being attorneys in private practice. Texas Democrats are more than twice as likely as their California counterparts to claim private-sector experience outside the field of law.

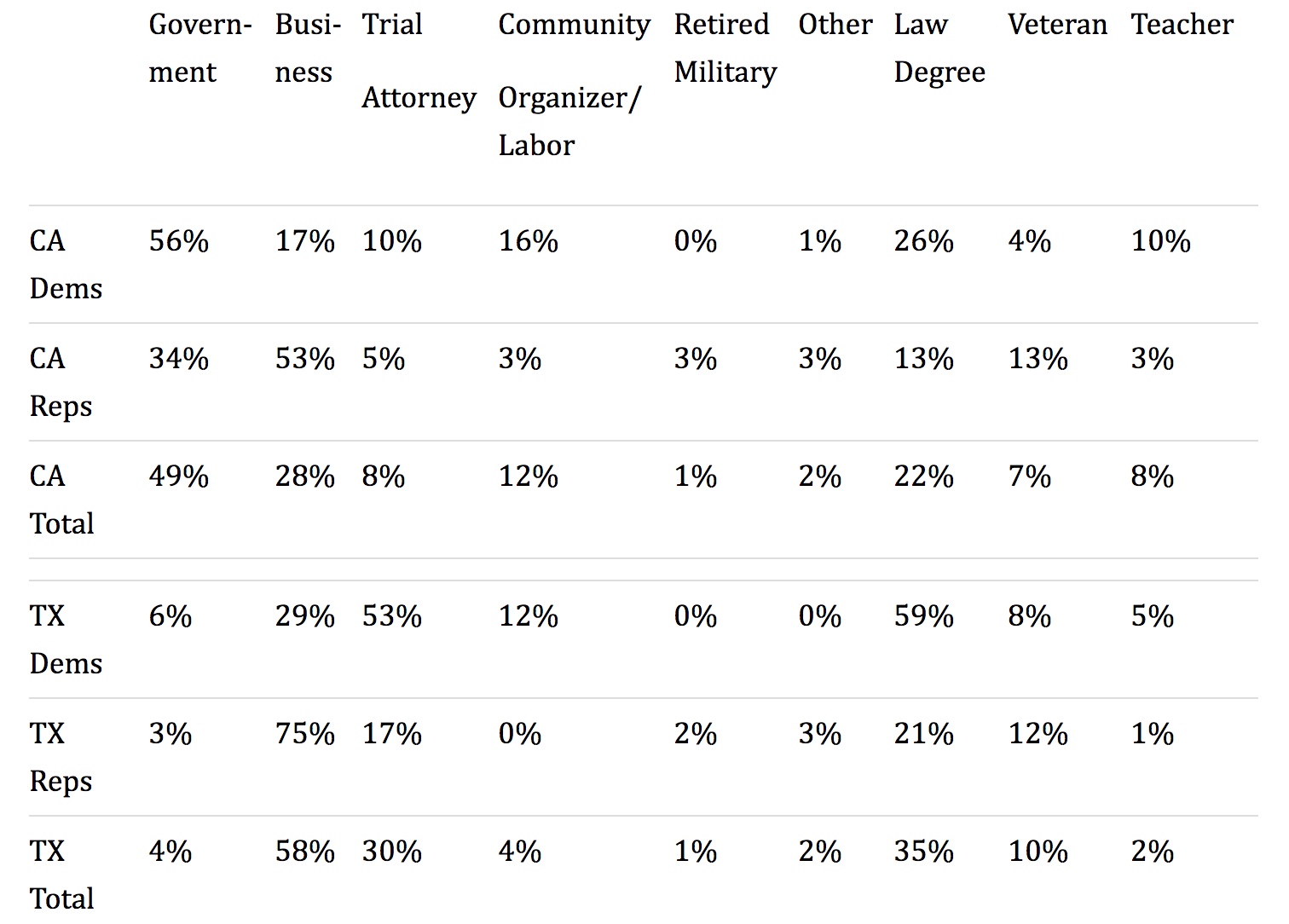

With the passage of three election cycles since I last looked at professional backgrounds of the lawmakers in California and Texas, I wanted to update and expand my study. Of the majority Democrats who dominate the California legislature, only 17 percent were in business prior to getting elected while another 10 percent worked as trial attorneys. In Texas, where Republicans run both houses in the state legislature, 75 percent earn a living in the private sector while an additional 17 percent work as lawyers.

This vast difference in legislators’ work experience leads to big differences in governance, with California boasting the highest income tax rate in the nation and a crushing regulatory burden while Texas has no income tax and light regulatory climate.

A Horde Of Professional Politicians

Of the majority of Democrats in California, 56 percent are professional politicians, former staffers to politicians, or workers getting a paycheck from a government entity. About 10.4 percent of the working age population in California works for the government. So, government workers are more than five times overrepresented in the California legislature than their numbers in the state would suggest.

Some 34 percent of California Republicans are professional politicians or government staffers.

In contrast, among the Republicans who run the Texas legislature, only 4 percent work in government (mostly teachers) or are retired from the military. About 10.9 percent of Texas’ working age population works for government (Texas has more teachers than does California).

Among Texas Democratic lawmakers, the number of government workers is only a little bit higher: 6 percent.

Comparing other professional experiences, 21 percent of Texas Republican lawmakers have a law degree, while 59 percent of Texas Democrats hold a law degree. In California, 26 percent of Democrats graduated from law school compared to 13 percent of Republicans. By contrast, less than one percent of the workforce in either state has a law degree.

About 4 percent of California Democrats are military veterans. California’s Republican elected lawmakers are more than 3 times as likely to have served in uniform: 13 percent. In Texas, lawmakers of both parties more closely reflect the share of the veteran population, with 12 percent of Republican lawmakers having military experience compared to 8 percent of Democrats.

This table summarizes lawmakers’ occupational background in California and Texas:

When lawmaking is turned into a full-time occupation, professionals will eventually dominate the field. In a representative democracy, this means that the people’s elected representatives will eventually reflect the government class and its attendant concerns and worldview. The consequences are easy to foresee: bigger government, higher taxes, and more powerful and arbitrary regulations.

California and Texas are both majority-minority states with large and diversified economies. But, California had the nation’s 6th-highest state and local tax burden in the nation as a share of income while Texas ranked 46th. That California has a professional legislature while Texas has a citizen legislature that must live under the very laws they pass likely explains much of this difference.