By Douglas Murray • National Review

It’s much more comfortable for those in power to go after amorphous concepts than to address real-world issues.

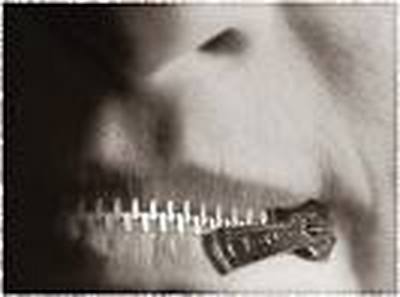

At the start of January this year a new law came into effect in Germany. The “NetzDG” law allows an un-named and unknown collection of government agencies and tech companies to police the Internet and remove content deemed to be “hateful” or otherwise deemed to constitute “hate speech.” Around the world politicians from other nations are looking at these laws with envy.

Of course, the whole notion of “hate speech” should warrant far more suspicion and push-back than it has done recently. Incitement to violence is already illegal in most countries. As are credible threats to kill someone. But “hate speech” brings a high bar down several pegs. And the problem with it is not only that it attempts to read purpose and imagined consequences into words, but that it inevitably comes framed to give ideological protection to whoever wields power at a particular point in time.

The temptation is obvious. In Germany “hate speech” can include words that are true and which are accurately critical or even merely descriptive of terrible events that are going on: particularly events that have followed from Angela Merkel’s open-borders policy of 2015. Doubtless the crack-down on her online critics is comfortable for Merkel and the government she has finally managed to assemble. But you have to have a remarkably short political memory to think that banning words that accurately describe situations is a wise way to try to order society.

But that is what an increasing number of prominent figures are trying to do. This week it was once again the turn of Mayor of London Sadiq Khan to admire Germany’s example. At a speech in Texas to the South by Southwest festival in Austin — and in accompanying videos and interviews — Khan praised the German law and bolstered his case by giving examples of vile things that people have said about him online. He urged his Texas audience to consider how such messages could deter people from entering politics or public life.

If someone like me is receiving these sorts of messages in a public environment, imagine how you feel as a young person, if you’re somebody who’s putting your head above the parapet. You’re going to think once, twice, three times whether you want to do so.

Of course, with Twitter and other social-media platforms the mayor of London knows that he is pushing at an open door. In recent weeks, a number of people have been suspended from or locked out of social-media accounts for tweeting things that include facts. For instance, in the U.K. you can now find yourself locked out of a social-media account for publishing facts about the endless, ongoing revelations of child-sexual abuse at the hands of gangs of men the British press euphemistically refer to as “Asians.”

Needless to say, this makes things infinitely more complex than they need to be. There has already been plenty of covering-up of these crimes (as shown this weekend when news emerged of yet another English city — Telford — where another 1,000 young girls turn out to have been raped in recent years. In most circumstances we believe that light is the best disinfectant. But not in these cases. Instead there is already a concerted society-wide effort to cover over these crimes, and now when they finally do emerge they are subject to an extra effort to police how such matters are written about. Or who can do that writing. So that one person may be allowed to repeat a fact whereas another might not. Rather than applying light as a disinfectant, an increasing number of tech companies appear keen to rub soil onto these open wounds.

But there is something else deeply suspicious about all this. Which is the way in which “getting tough” or “cracking down” on tech companies has become one of the new ways to divert ourselves from addressing real-world issues.

After the London Bridge attack last summer (the third such attack in a row) the U.K. prime minister, Theresa May, announced that tech companies must do more to tackle “radicalization.” In fact there was no evidence that the culprits had ever been radicalized online. They all knew equally bad people, and at least two of them should never have been in the country in the first place. One had even appeared on a TV documentary on Channel 4 called ”The Jihadi Next Door.” So if the security services, tech companies, or politicians had wanted to discover that one of the soon-to-be terrorists was a bad egg they didn’t need any new Internet laws. They only had to turn on the television. The fact that people who can’t do that now want to police the web is a matter for anyone to marvel at.

But of course it is so much more restful to ask someone else to address a near-impossible goal than it is to conquer a possible one yourself. While Mayor Khan was lecturing his audience in Austin he had failed to identify a problem far closer to his home. In particular the fact that during his time as mayor knife-crime and acid attacks in the capital have rocketed. Sixteen people have been stabbed to death in London already this year. Almost all of this is gang-related, and much of it is immigrant-gang-related. Where the trend for throwing acid in people’s faces has come from, who would dare to guess?

But this is becoming the tone of the age. Commit yourself to cracking down on something amorphous like “hate” and the murder levels can look after themselves.