By Jonathan S Tobin • National Review

The question was a reasonable one, but the answer was not. When the hosts of MSNBC’s Morning Joe program asked why President Trump had congratulated Russian president Vladimir Putin on being reelected, former CIA director John Brennan pulled no punches. In answering the leading question that implied Trump may be afraid of Putin, Brennan said, “The Russians may have something on him personally.” The Russians, he said, “have had long experience of Mr. Trump, and may have things they could expose.”

Coming from just another foe of Trump — which Brennan, an Obama loyalist, certainly is — the assertion could be dismissed as just a partisan cheap shot. But coming as it did from a career intelligence officer who served for four years as the head of the American intelligence establishment, this had to be more than a baseless conjecture.

Except it wasn’t.

By the end of the day, Brennan admitted his wild charge was not based on any actual information or intelligence revealed to him during the course of his duties but just a willingness to assume the worst about Trump. In a written response to questions from the New York Times, he said, “I do not know if the Russians have something on Donald Trump that they could use as blackmail.”

In a world in which journalists treated unfounded assumptions as just that, rather than headline news, Brennan’s charges would have been dismissed. But though the Times knew the accusation was baseless by the time it published its article on the subject, the paper buried the lead. The headline on the story was “Ex-Chief of the C.I.A. Suggests Putin May Have Compromising Information on Trump.” Brennan’s walking back of his charge didn’t appear until the eleventh paragraph of the story.

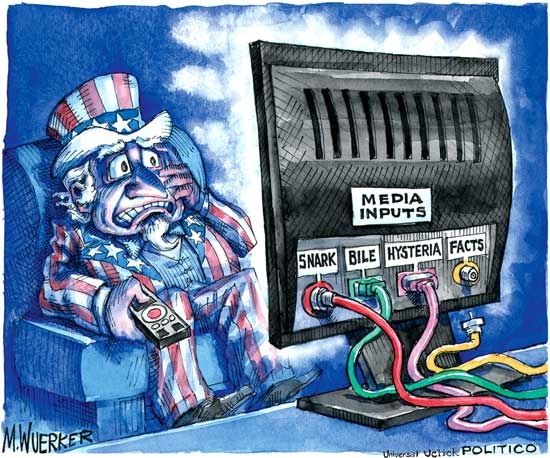

The point here is not just the decision of the editors of the Times to downplay information that undermined the entire story. Nor is it only that the rest of the mainstream media played it the same way. In particular, the coverage on MSNBC and CNN consisted of highlighting the accusation, treating it as a proven fact, and then following up with panels in which others speculated as to what evidence might substantiate Brennan’s charge, even though he had already admitted he had no such information. This episode encapsulates most of the media’s coverage of the entire Russian-collusion investigation over the last year, in which speculation about Trump’s guilt is always assumed to be true even if proof is never forthcoming.

The case of the Brennan smear is, however, instructive in that it shows how coverage of Trump and Russia works. When Brennan spoke of the Russians’ having something on Trump, not one member of the panel asked the former Obama staffer whether his opinion was rooted in actual knowledge rather than pure speculation. Nor did many others ask that question over the course of a day in which Brennan’s comment was among the most discussed stories.

That fits a pattern that applies to every stage of the Russian-collusion investigation.

More than a year into the Trump presidency and the appointment of Robert Mueller to lead a special investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 election, information about the subject is still scarce. Speculation about the dearth of knowledge regarding what happened or what exactly Mueller has discovered is understandable. But in most of the media, that lack of information hasn’t stopped both reporters and commentators from jumping to conclusions about Trump’s being in big trouble every time even the smallest tidbit about the probe is aired.

Until Mueller finishes his work and issues a report, we won’t know what he has found. Like virtually every other special counsel, armed with an unlimited budget and near plenary powers to chase down any potential crime no matter how tenuous its link to his original brief, Mueller is taking his time. But after his indictments of Russians for their activities, the only crimes committed by Americans that he appears to have found get us nowhere near a finding of collusion between the Trump campaign and the Russians. While there were scattered contacts, there is still no evidence they cooperated on anything. At this point, and since the charges against the Russians were not tied to those against Americans with whom they might have colluded, it is not unreasonable to think that there may be none.

What we do know is that President Trump does appear to have a soft spot for the Putin regime and seems unwilling to listen to the counsel of those who urge him to be more guarded in his statements about the subject.

Is that enough, as Brennan seems to think, to fuel a charge that he might be under some sort of pressure from Russia?

The obvious answer is no. Trump has been consistent throughout his campaign about believing in better relations with Russia and for his lack of outrage about its foreign mischief making. This is a terrible idea, as Moscow has proved time and again over the last year, since thwarting U.S. interests is, along with reassembling the old Soviet empire, one of the keynotes of Putin’s foreign policy.

Yet you don’t have to be a Russian agent of influence to back policies or gestures that are favorable to Putin. After all, President Obama made the same foolish gesture for which Trump has been lambasted this week: calling to congratulate the authoritarian leader after winning a rigged election in which his victory was foreordained. Obama began his first term with a comical effort to “reset” relations and continued to defend Russia. He mocked Mitt Romney for declaring Russia to be America’s prime geostrategic foe in their 2012 foreign-policy debate, a stance that is Democratic-party orthodoxy now that détente with Putin is identified with Trump. Just as bad, in an infamous hot-mic moment, he told Putin’s puppet Dmitry Medvedev to tell “Vladimir” that he could be more “flexible” in bowing to Russian demands after he was reelected.

None of that constituted proof that Obama was in thrall to Putin. His belief in showing weakness to Russia was sincere. But Trump’s sporadic continuation of this imprudent policy — for which Brennan was at least partially responsible — is assumed without proof as being prima facie evidence of treason, even though Trump has also done some things, such as his arming of Ukraine, to offend Putin.

Theoretically, Brennan could be right. But to assume without proof that the only possible motive for a policy choice is a criminal connection isn’t journalism. At best, it’s a highly partisan talking point. At worst, it’s a smear.

It used to be that partisan assumptions fueled by pure speculation and unaccompanied by proof didn’t pass the smell test at any major network or newspaper. The fact that political smears of this sort have now become not only possible but also normal says a lot about the way animus for the Trump administration has distorted much of the media’s judgment and coverage. If liberals want to know why conservatives no longer trust the media about Trump even when the facts are on their side, they need look no further than the way the media covered Brennan’s unfounded accusation.