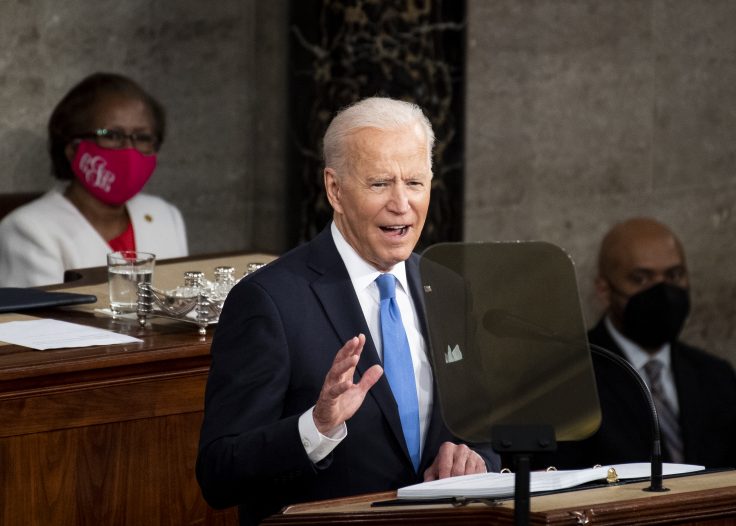

President Biden’s address to a joint session of Congress underscored this administration’s left turn. The speech was a laundry list of progressive priorities in domestic, foreign, and social policy with a price tag, when you add in the American Rescue Plan, of some $6 trillion. Biden’s delivery, heavy with improvisation, only slightly enlivened a prosaic and unoriginal text. Biden repeated lines from both Bill “the power of our example” Clinton and Barack “the arc of the moral universe” Obama. But it wasn’t just the words themselves that made me think of Biden’s most recent Democratic predecessors. The scope of his plans, increasing government’s role in just about every aspect of American life, also brought to mind the Democrats who tried to govern as liberals after campaigning as moderates.

I’m old enough to recall the last president who vanquished Reaganism. Obama spoke of “fundamentally transforming the United States of America,” and came to Washington in 2009 with the aim of changing the trajectory of the country just as Ronald Reagan had done three decades earlier. Shortly before his one hundredth day in office, he delivered a speech at Georgetown University where he promised to lay a “new foundation” for the country. His friends in the media hailed him as the second coming of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. “Barack Obama is bringing back the era of big government,” historian Matthew Dallek and journalist Samuel Loewenberg announced in the New York Daily News.

We know how that turned out. The GOP captured the House in 2010. By the time Obama left office, Republicans had full control of Washington and were dominant in the states. Reaganism survived. And now, 12 years later, the cycle is repeating. This time it’s President Biden who is likened to FDR. It’s Biden who is said to have interred the idea of limited government. It’s Biden who is marking his first 100 days in office with plans to spend trillions on infrastructure, green energy, health care, and elder and child care. The political setbacks of the Obama years didn’t temper Biden’s ambitions. They intensified his desire to leverage narrow congressional majorities into sweeping expansions of the welfare state.

Why does Biden think he can avoid Obama’s fate? Like a good lawyer, he has a theory of the case. It goes like this: Neither Bill Clinton nor Barack Obama spent enough money to ensure a strong economic recovery. They didn’t emphasize jobs above all else. Their caution was responsible for Democratic losses in the midterm elections. And all it takes is GOP control of one chamber of Congress to spoil a liberal revival. By opening the floodgates of federal spending, Biden hopes to deepen and extend the post-coronavirus economic boom. Growth and full employment will prevent a Republican takeover. And a second Progressive Era will begin.

The problem with this theory is its selective misreading of history. It wasn’t just the economy that sank the Democrats in 1994 and 2010. It was independent voters who turned against presidents who campaigned as moderates but governed as liberals. Nor did rising unemployment stop Republicans from picking up seats in 2002. And an economic boom didn’t save the House GOP in 2018. In every case, assessments of the president—among independent voters in particular—mattered more than dollars and cents. By committing himself to the idea that massive spending will safeguard the Democratic Congress, Biden may be inadvertently guaranteeing the partisan overreach that has doomed past majorities.

Biden doesn’t give enough credit to the record of his Democratic predecessors. The unemployment rate was 7.3 percent in January 1993 when Bill Clinton was inaugurated. By November 1994, it had fallen to 5.6 percent. Meanwhile, the economy grew by 4 percent in the third quarter of 1994. Nevertheless, the Republicans won control of the House for the first time in 40 years and the Senate for the first time in 8 years. Why? Because Republicans won independents 56 percent to 44 percent. Voters who had backed Ross Perot in 1992 swung to the GOP. Voters’ top priority in the exit poll wasn’t jobs. It was crime. And the failure of Clinton’s unpopular health plan didn’t help.

The 2010 midterm had similar results. The economy, while nothing to brag about, was nonetheless improving. Unemployment had been falling since October 2009. Growth, though anemic, had also returned. Republicans gained 63 seats in the House and 6 in the Senate because independents rejected President Obama’s governance. They backed Republicans 56 percent to 37 percent—an 8-point swing against a president they had supported in 2008. Why? Part of the reason was the economy. But the Affordable Care Act was also significant. Health care was voters’ second priority in the exit poll. A 48 percent plurality called for Obamacare’s repeal.

Biden’s theory also omits the contrary examples of recent Republican presidents. In November 2002 the unemployment rate was higher, and growth lower, than in November 2000. But the GOP had a good year anyway thanks to President Bush’s high post-9/11 approval ratings and a tough but effective campaign on national security.

The 2018 midterm is further proof that campaign results are not a direct function of economic performance. Democrats won control of the House despite full employment and sustained growth. Independents, who had narrowly backed President Trump in 2016, turned against him and voted for Democratic candidates by a 12-point margin. No mystery why: A 38-percent plurality of voters said they were voting to oppose Trump, whose strong disapproval rating was at an incredible 46 percent in the exit poll. Health care ranked as the top issue, with voters recoiling at the prospect of an Obamacare replacement that failed to cover preexisting conditions.

Not only do the data show that the economy is less important to the midterms than many assume, they are also a reminder that the first hundred days do not define a presidency. The fate of a president and his party depends more on his ability to maintain popularity and on his performance during unanticipated crises. While Biden’s approval ratings continue to be positive and his disapproval low, there are some warning signs: His approval among independents ranges between the mid- to high-50s, and a majority of voters disapproves of his handling of migration along the southern border. Focused on his grand plans for the economy, Biden might dismiss voter concerns over immigration, crime, and inflation until it is too late.

Sure, Biden might avoid making Barack Obama’s mistakes. But he has plenty of time to make mistakes of his own.