In the late spring, as coronavirus cases in the U.S. were trending way down and vaccination rates were trending up, Dr. Lucy McBride and three of her colleagues authored an optimistic Washington Post op-ed with a clear and straightforward message: “It’s time for children to finally get back to normal life.”

The risk to children was too low to justify burdensome restrictions over the summer. And when school begins, kids should return “without masks and regardless of their vaccination status,” the four doctors wrote. “Even small steps toward normality can have a large impact on a child.”

After more than a year of confusion, fear, death, school closures, and mask mandates, here, finally, was a group of respected doctors, writing in one of the nation’s most respected newspapers, that the time had come for kids to get back to just being kids, no masks required.

Fast-forward three months: The highly contagious Delta variant is surging, particularly in hot Southern states and in states with low vaccination rates. Intensive-care units are overflowing, and COVID-19-associated hospitalizations of kids and teenagers are at an all-time high. Virus-related deaths are rising again.

And with the change in conditions, McBride’s messaging has changed along with it.

“Right now, with Delta running roughshod through the country, I think it’s appropriate for unvaccinated people to wear masks indoors in areas where transmission is high,” McBride, a Harvard-trained physician and practicing Washington, D.C., internist, told National Review. “I would want to mask my unvaccinated child in a state like Mississippi or Florida at this moment.”

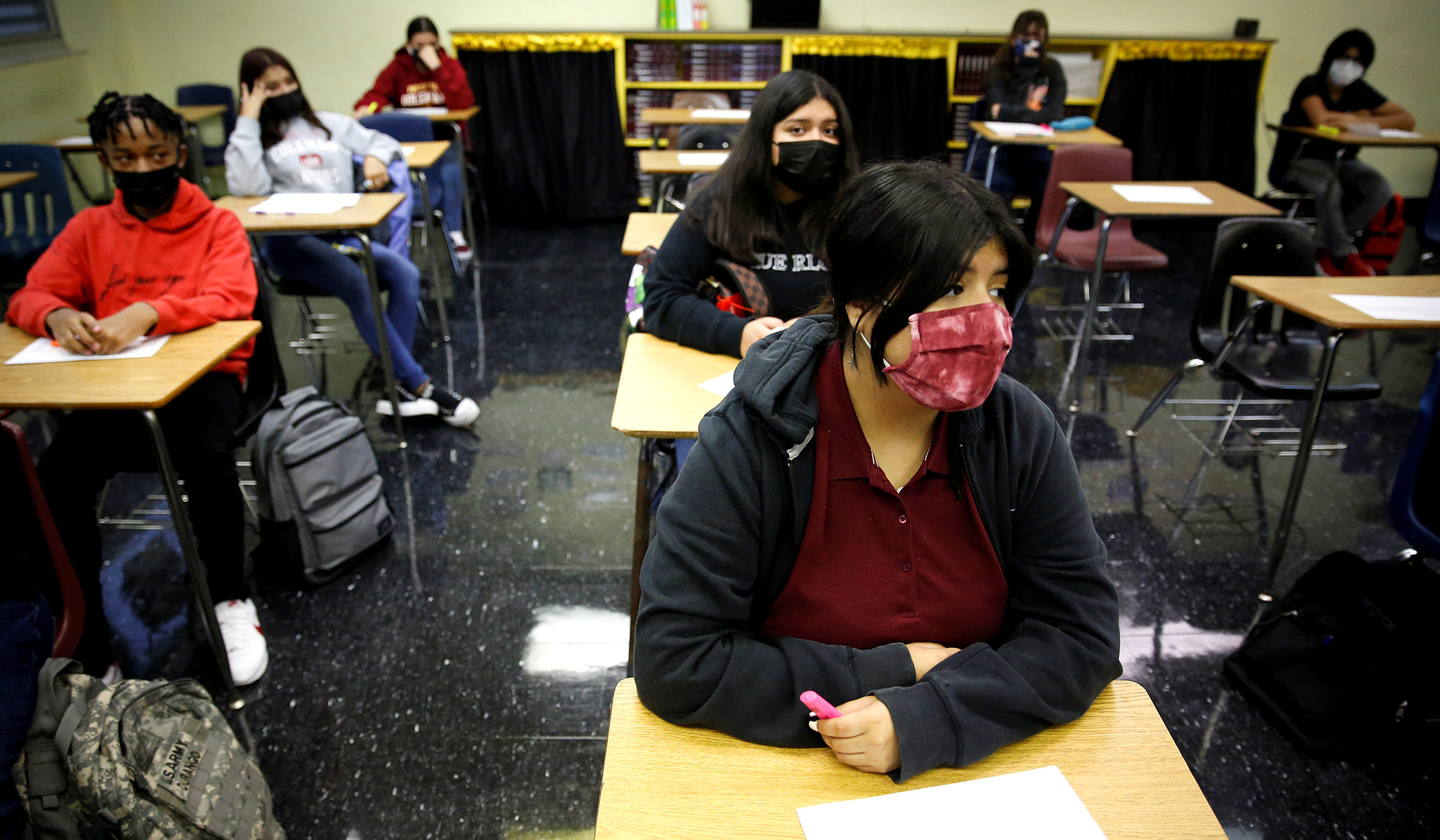

This latest coronavirus surge began in the weeks before schools reopened in many states, leading to statehouse fights and heated school-board debates over mask mandates and parental freedom.

In Florida, the school boards in at least five counties have voted to defy governor Ron DeSantis’s order, which empowers parents to decide if they want their kids to be masked in school. In Hillsborough County, more than 10,000 students and 300 school staff members were quarantined last week. Earlier in the month, before classes resumed, three unvaccinated Broward County teachers died in a 24-hour span. DeSantis has questioned the effectiveness of mask mandates in schools, saying, “There’s not much science behind it.”

In Mississippi, 13-year-old Mkayla Robinson died of coronavirus complications in mid-August after attending eighth grade for a week at a school where masks weren’t required. It’s unclear if the teen contracted the virus at school. Her mother told a local TV station that Mkayla was a healthy kid with no pre-existing illnesses. Mkayla’s death came on the heels of 16-year-old Jenna Lyn Jeansonne’s death in the state in late July.

Some Mississippi schools already have reverted to virtual learning because of COVID outbreaks. Only 36 percent of eligible Mississippians are vaccinated, one of the lowest rates in the country.

The Delta surge has left parents confused, and it has scrambled the way many of them are thinking about how they should protect their families.

The Delta surge also has led to a renewed debate in the medical community about just how effective a COVID-19 mitigation effort masks really are for kids, with some doctors saying there isn’t enough science to back universal mandates in schools, and arguing that for some kids the masks may do more harm than good. Other medical professionals argue that the protection that masks provide — however small — far outweighs their downsides.

“People have very strongly held opinions on masks and children with very little information,” Dr. Marty Makary, a surgeon and professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, told National Review. The effectiveness of masks on children has been woefully understudied, so most of what we know about the benefits for kids is extrapolated from adults, Makary said.

In July, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated its guidance for schools, recommending that all adults and children wear makes indoors. The CDC reports that multi-layered cloth masks can block up to 80 percent of respiratory droplets. A recent Duke University study found that widespread mask use in schools can effectively prevent COVID transmission.

But a New York Times Magazine article published on Friday noted that a groundbreaking CDC study published in May found no statistically significant benefit from requiring students to wear masks. The Times article also criticized the Duke study for not using a comparison group of unmasked students, making it impossible to isolate the effects of masks. A National Institutes of Health review last year found that cloth masks have limited efficacy in preventing viral infections, depending on the materials used, the number of layers, and how the mask fits.

Many European countries, including the U.K., France, Switzerland, and all of Scandinavia, have exempted children from wearing masks in classrooms, with no evidence of more outbreaks in those schools compared with U.S. schools where masks were required last year, the Times reports.

Makary recently co-authored a Wall Street Journal op-ed that ran under the headline “The Case Against Masks for Children.” But Makary said the headline is not exactly representative of his position. He is not an opponent of masks for children generally. He’s been an advocate of most people wearing masks since the beginning of the pandemic. As a surgeon, he wears a mask.All Our Opinion in Your Inbox

“Masks reduce transmission, and I believe even the very flimsy, low-value cloth masks do something for kids,” he said. “I would say that wearing them in an area of an active outbreak is a good idea, even though the benefit may be minimal.”

But children are not homogenous. Some live with adults who are vaccinated, some don’t. Some live in communities where major outbreaks are occurring, some don’t.

Makary’s concern is for kids who legitimately struggle with masks: kids with physical and cognitive disabilities, kids with myopia whose glasses get fogged when they’re masked, kids with severe acne, kids with anxiety and depression from wearing masks, kids with hearing impairments or issues with phonetic development. He worries that covering the faces of children, particularly young kids and children with disabilities, could lead to developmental delays.

In some cases, the risk-to-benefit ratio falls on the side of a child not wearing a mask, he said.

In terms of effective mitigation measures to protect kids from the virus, masks are pretty far down on the list, behind vaccinating adults and teens, ventilation, social distancing, podding kids in school, and hygiene, Makary said.

“So, we have had this massive culture war over maybe what’s the sixth mitigation step, which has a small impact if any, and has not been formally studied,” he said.

Most kids who contract COVID-19 manifest with mild symptoms, and often no symptoms at all. Since the start of the pandemic, there have been fewer than 500 deaths involving children under 18, out of more than 600,000 total deaths nationwide, according to CDC data. For the week of July 31, the rate of hospitalization with COVID of children five to 17 was 0.5 per 100,000, according to the Wall Street Journal. A study of children and young people in England found kids generally have a lower risk of death or serious outcome from COVID than even vaccinated 30-year-olds. But children are making up a growing share of serious COVID cases now.

“A percentage of a larger number is a larger number,” said Dr. Charlotte Hobbs, a pediatric disease specialist at the University of Mississippi Medical Center and an advocate for universal masking in schools. There are concerns for kids besides just death from COVID, she said.

As of July 30, the CDC reported that more than 4,400 children in the U.S. have contracted post-COVID Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children, a potentially lethal condition that causes parts of the body — including the heart, lungs, kidneys, brain, and eyes — to become inflamed. And Hobbs noted the long-term effects of COVID still are not well understood, though a large British study published this month found that only about 4.4 percent of infected kids had symptoms for longer than 28 days, with the most common symptoms being fatigue, headaches, and loss of smell. Less than 2 percent had any symptoms after 56 days.

Because kids under 12 aren’t eligible for a vaccine, adults need to do everything they can to protect them, including getting vaccinated and supporting masks in schools, she said.

Some people who got vaccinated earlier in the year and thought they could put away their masks for good are having second thoughts amid the Delta-variant surge.

Jeff Navarro, 68, who has twin 16-year-old sons in high school in Amory, Miss., was looking forward to life without masks, after he, his wife, and his kids all got vaccinated. But as an older parent, Delta has him worried, and he supports the mask mandate his school district imposed.

“I’ve learned at 68 years old that no one is bulletproof,” he said. “I take it seriously. I follow the science. I certainly do not understand it enough to dispute it; therefore, I have to accept it.”

Sean Kruer, a father of two young children in Huntsville, Ala., has been a strong supporter of a school mask mandate in his community. He and his wife had serious discussions about pulling their kids out of school if there was no masking requirement.

“From a public-health policy perspective, universal mask mandates absolutely make sense,” Kruer said. “So, as much as I understand that it would be nice if things had continued the way that it looked like they might in May, that’s not the reality. And continuing as if it were and being petulant about it isn’t helping anybody.”

Melissa Bernhardt, the mother of a high-school student and an elementary-school student in Jacksonville, Fla., said she questions the science around masks. She’s not against people wearing masks, she said, but she doesn’t believe they should be forced on all kids.

She described one of her sons as particularly high energy, but she said he became lethargic and fatigued during school last year. She believes it’s because he had to wear a mask.

Bernhardt’s kids attend private school because she thought they wouldn’t impose a mask requirement. But, she said, she was wrong.

“The private schools really disappointed me,” she said. “They have committees with doctors, and all the doctors that are on the committees are not only pro-mask, they’re pro-vaccine.”

Bernhardt declined to discuss her vaccination status, but she said she feels protected because she contracted COVID early in the pandemic and has antibodies.

Hobbs said that even though kids don’t frequently get as sick from COVID as adults, “they can and they do, and we’ve had kids who have died. . . . Any pediatric death in my mind is one too many, especially when we know that this is preventable. We have a vaccine for those who are eligible, and we know that masking works.”

McBride, the D.C. internist, said parents need to know that there is an off-ramp down the road. She believes the CDC and other public-health agencies need to offer clear metrics about when schools can start rolling back mitigation efforts, including mask mandates.

“After all, COVID-19 isn’t going away. It’s going to be an endemic virus, and we know that there are enormous downsides (of pandemic restrictions, particularly) for kids,” she said. “We can’t mask indefinitely, nor should we.”

Hobbs said it’s too soon to say when that off-ramp will arrive. No one predicted the emergence of the hyper-transmissible Delta variant six months ago, and no one knows what variants will emerge in the future amid a backdrop of unvaccinated populations. Only 51 percent of Americans of all ages are fully vaccinated, including people not eligible for the vaccine.

“Until we basically have all of those eligible to get vaccinated vaccinated, it is most likely that we will not see the end of this anytime soon,” she said. “In the absence of people getting vaccinated and doing what they can to mitigate the spread of the virus, which itself will lead to continued emergence of new variants, then I don’t know what the end of this road will be.”

Parents are entitled to worry about the virus, McBride said. “It’s how we survive,” she said. “But we also have to acknowledge that worry can take on a life of its own and cause its own problems. I think it’s a very hard time for everyone.”

Now more than ever, she said, it’s important for people to have a trusted pediatrician or family doctor to help them take public-health advice and make nuanced personal health decisions.

“There’s no way the CDC can possibly speak to every individual,” she said.

The mask debate, she said, has become divisive and political. McBride agrees with Hobbs and Makary that the most important thing adults can do at the moment to protect kids is to trust the science, listen to their doctors, and get vaccinated.

“What we really need to be doing,” McBride said, “is getting dose one into people who are unvaccinated.”