It’s a remarkable feat—something not just anyone could accomplish. Yet in just a few short months, President Joe Biden managed to turn the recovery around. It’s not clear how he did it, but the boom for which he liked to take credit is officially over.

Of course, the White House doesn’t want to say that. It would be politically bad to acknowledge the situation that now exists. To avoid that, senior presidential aides and Cabinet secretaries like the Treasury Department’s Janet Yellen have been forced to turn rhetorical cartwheels while trying to explain that it isn’t really what the data tell us it is.

Team Biden has masterfully avoided the invocation of the word usually employed after two consecutive quarters of what the economists call “negative growth.” Call it what you want—some good alternative phrases like “economic Joe-down” and “Joe-cession” have already seeped into the conversation—the economic numbers don’t help Biden’s cause right now.

His unpopularity isn’t new news. A recent CNN poll found that 75% of Democrats who plan to vote in 2024 hope to have someone other than Biden for whom to cast their ballots. State by state, Biden’s favorable/unfavorable ratings are underwater in more than 45—including such liberal bastions as Massachusetts and even his home state of Delaware, where he’s down by seven.

Why is he so unpopular? Real wages are falling, income is down, and prices are up. That’s fact, not opinion or carefully structured analysis. Biden may think there’s plenty of good news out there, that it “doesn’t sound like a recession to me,” but it sure feels like a recession to the American people.

It would seem all that is good for the GOP’s prospects to pick up control of the U.S. House and Senate come election time—and by wide margins. The anti-Biden tide is going to swamp some boats that expect to ride the storm out—as happened in 1978, 1980, 1994, and 2010, when unpopular policies pushed by the occupant of the White House cost the president’s party seats it should not have lost.

How, then, with the Democrats seemingly in their worst political shape in nearly 50 years, does one explain a spate of recent polls like the one released last Tuesday in USA Today, showing them with a four-point lead—44% to 40%—over the GOP on the congressional generic ballot? Especially, that is, after the Republicans have been nearly double-digit dominant on the question of “Which party do you want to control Congress after the next election?” for many months now.

It doesn’t make sense—especially, as Rasmussen Reports said last Monday, with just 23% of likely U.S. voters thinking the country is headed in the right direction. The reason for the bump producing this apparent reversal of the Democrats’ political fortunes may have something to do with statistical manipulation. Pollster John McLaughlin told this publication that the USA Today poll had the two major parties “in equilibrium at 31%,” but because it sampled registered voters and not those considered likely to vote, “it waters down the GOP generic vote” considerably. “A lot of [the Democratic] respondents will not vote,” he added.

He may be right. A Rasmussen Reports poll of likely voters released on Friday found Republicans with a five-point lead on the generic ballot. That’s the upside. The downside is the voters may be souring on the GOP—and these new polls may be right, because the GOP is failing to offer voters an appealing alternative to the Biden agenda.

American elections are usually binary: this candidate or that one. Third-party candidates rarely win, and rarely have an impact. Most people pick either the Democrat or the Republican when they pull the lever. And right now, the GOP seems headed to a majority by default. They’ll win because they’re not “them”—Democrats. Biden and the progressives have overreached, something even the USA Today poll showed. They aren’t winning converts to their cause; they’re losing them.

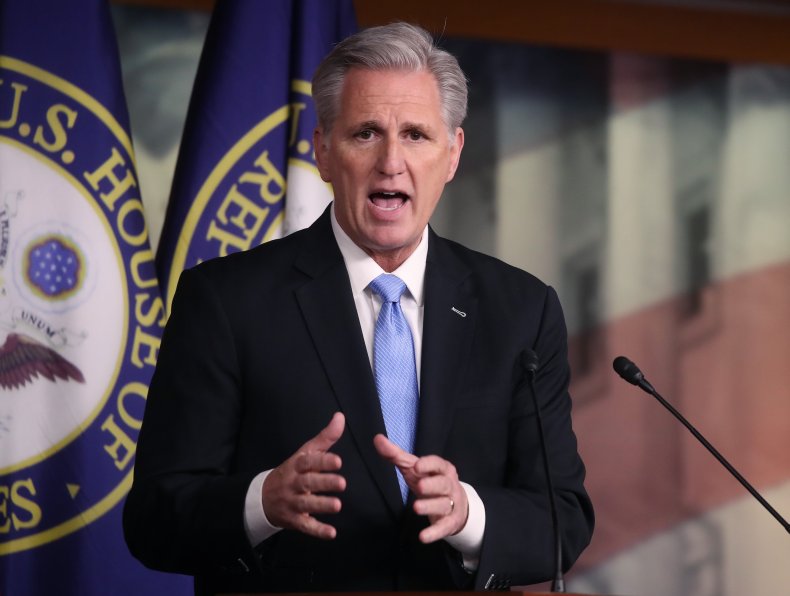

If the GOP wants to lock down its hoped-for majority down, it needs to explain to its whole coalition of voters—the independents open to voting Republican, the moderates, the free marketeers, the social conservatives, and others—what the party’s plan is to get the economy moving, secure America’s borders and position in the world, and bring back the nation’s spirit. And the GOP must do so without driving its likely voter blocs into separate corners.

It’s a tall order that party leaders seem reluctant to embrace. They have about 100 days to come up with a plan to bring all these parts together and help voters make up their minds. In doing so, if that’s what they intend, they need to remember former House Majority Leader Dick Armey’s axiom: “When we act like us, we win. When we act like them, we lose.”