Seafood Is Yummy; Bureaucratic Mismanagement Is Not

Public policy on fisheries continues to rely largely on outdated central planning. This has led to hazardous fishing conditions, depletion of many fish stocks, and economic inefficiency.

An innovative approach – dubbed “catch shares” – has emerged in recent decades. Where it has been tried, it has been successful, both for fishing production and conservation. Catch shares involve recognizing fishermen have property rights – the “shares” – they may use, lease, or sell.

Initiating more market-oriented policies in any area necessarily involves creative destruction. Key to any campaign to broaden the reach of catch shares will be: 1) developing principles for transitioning from the outdated model; 2) highlighting the negative effects of continuing under the outdated model; and 3) upholding the success of fisheries operating under catch shares.

Introduction

A Straightforward Industry

Fishing as an industry has existed for thousands of years. While technological advances have enabled the scope of fishing to expand enormously, the fundamentals remain the same. It’s people making a living on boats, while figuring out how to get slippery creatures out of the water. From there, they can be transmitted to land to be broiled in butter, lemon, and garlic, or such seasonings as may be desired.1

A Problem and Its Solution

The broiling-in-butter-and-garlic thing sounds pretty good, right? Most people think so. Not only did the global tonnage of seafood consumption more than triple from 1961-2007, but consumption per person nearly doubled.2 That’s a lot of fish. (It’s also a lot of butter, but that’s beyond the scope of this article.)

The increase in demand has contributed to intense pressure on fisheries. Since governments typically have jurisdiction over the waters, relevant authorities have tried to stay ahead of the fishermen by regulation. This has meant capping fishing, initially by instituting “fishing seasons.” This is basically a clever way of marketing non-seasons when fishing is prohibited. A variety of other restrictions then follow, from licensing to equipment restrictions to reporting requirements. Seasons themselves end up shortened, sometimes to absurd lengths measuring in days instead of months.

These can all be well-intentioned regulations but ultimately they merely slow rather than defuse the fishing arms race, with many fishing stocks both in the U.S. and abroad depleted.3

One problem is the adversarial nature of having regulators chasing after fishermen, and fishermen, often having greater knowledge of the fish and the terrain, consistently gaining the upper hand. Fishermen typically are also better-motivated, fishing for their livelihoods. Regulators, at least in the U.S., tend to receive the same salaries regardless of the status of resources under their purview.

Changing the paradigm and enlisting the fishermen is a proven solution. Dubbed “catch shares,” it assigns quotas to individual fishermen. The shares then become the property of the fishermen, to be used, sold, or traded as the owners see fit. Crucially, fishermen are then empowered to fish during safer weather and when it’s most economically feasible, with seasons typically lengthening once catch shares have been implemented.

Misinformation about the nature of catch shares is a hurdle, as are concerns over consolidation of fishing fleets. Stakeholders in fisheries still under a central planning regime will likely need to be mollified moving forward.

An Industry Under Pressure

External Pressures: Demand…

Economic pressures affect the fishing industry like any other. In the case of the fishing industry, seafood continues to be very popular. This is due to a variety of factors, but perhaps one of the most significant marginal factors is nutritional health benefits.4 In simplistic terms, oils that remain liquid at the lower temperatures experienced by sea creatures can be more easily processed through human digestive tracts. Those oils themselves feature other healthy properties.

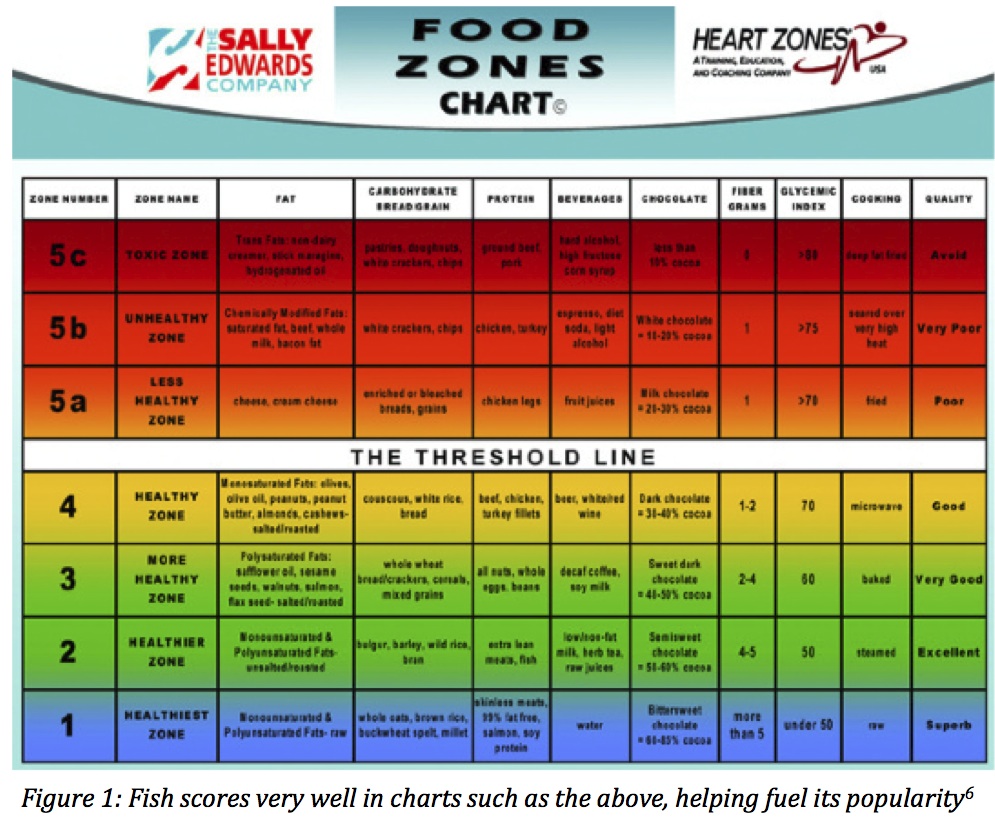

The market has also shown an increased demand for healthier foods in recent years (see Figure 1). One vegetarian working with a vegan-friendly health, wellness and skincare company commented to us that even though she avoids food from land-based animals – beef, pork and even chicken – she eats seafood regularly due to the recognized health benefits and its value as a source of protein.5 We didn’t ask her how much butter and garlic she uses, but clearly health concerns are contributing to the global demand pressures on the industry.

…And Competition

Fishermen have been squeezed on prices from the influx of farm fishing, particularly from overseas. The Alaska wild salmon fishing industry came under such pressure in the early 1990s, with salmon flooding into the market from fish farms, chiefly in British Columbia, Norway, and Chile. Due to the fundamentally simple nature of fishing – men on boats – many wild salmon fishermen simply switched to different stocks, particularly king crab and halibut. This resulted in a glut of fishing of those stocks – a type of domino effect. That helped lead to Individual Fishing Quotas – a type of catch shares program – being enacted for king crab and halibut.

As one industry veteran explained it, “in fishing, switching stocks is easy, if you already own your boat. You may need to buy a little different gear, but that’s a minor expense.” In this way, stocks are not insulated from pressures on other stocks they’re geographically close to.

The Quest for Moby Dick – Figuratively Speaking

If Ahab Was a Federal Bureaucrat

External pressures on the fishing industry, coupled with the internal pressures of ingenuity from fishermen aided by new technology, threaten to exhaust fishing stocks. This has resulted, over time, in a wide array of mandates from government regulators attempting to rein in overfishing. Unfortunately, a failure of imagination over the past century has at best slowed the bleeding, and at worst has accelerated the problem.

The U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy’s 2004 report sums up the cat-and-mouse aspect well:

Recognizing the dangers posed by overfishing, managers began to regulate fishermen by placing controls either on input or output. Input controls include such measures as closing access to fisheries by limiting permits, specifying allowable types and amounts of gear and methods, and limiting available fishing areas or seasons. Output controls include setting total allowable catch (the amount of fish that may be taken by the entire fleet per fishing season), bycatch limits (numbers of non-targeted species captured), and trip or bag limits for individual fishermen.

These management techniques create incentives for fishermen to develop better gear or to devise new methods that allow them to catch more fish, and to do so faster than other fishermen, before any overall limit is reached. They provide no incentive for individual fishermen to conserve fish, because any fish not caught is likely to be taken by someone else…if managers limited the length of the boat, fishermen increased its width to hold more catch. If managers then limited the width, fishermen installed bigger motors to allow them to get back and forth from fishing grounds faster. If managers limited engine horsepower, fishermen used secondary boats to offload their catch while they kept on fishing.

One input control many managers turned to was limiting fishing days…[i]n the historically year-round halibut/sablefish fishery in the Gulf of Alaska, the fishing season dwindled to less than a week by the early 1990s.

In addition to conservation concerns, the race for fish can create safety problems. Faced with a sharply curtailed amount of time in which to harvest, fishermen often feel compelled to operate in unsafe weather conditions while loading their boats to capacity and beyond.7 [emphasis added]

The paradigm under which regulators typically operate is fatally flawed. It’s not surprising, in retrospect – the interest of a bureaucrat is in preserving power, both professionally and as a function of human nature. Meanwhile, some officials may be adherents of environmental ideologies (or at least environmentalist premises) that exacerbate the adversarial relationship with the men and women trying to make a living under their purview. The typical thought process for a regulator may well be:

I am responsible for maintaining these fishing grounds. These fishermen come here to fish, and I’m not allowed to send them away. However, I will make rules for them to follow. And if they find loopholes in the rules to do things I don’t like, I will make new rules. And if they find loopholes in the new rules, I’ll chase them with yet more new rules. I’ll chase them round Good Hope, and round the Horn, and round the Norway Maelstrom, and round perdition’s flames before I give them up.8

Captain Ahab may seem a harsh analogy. But consider, the traditional central planning model of fisheries management is in a slow-motion death spiral. Nothing suggests the high demand for seafood will abate.  This affords no margin for error for the broad mismanagement of regulators unable to keep up with fishermen who, in the aggregate, will continue to outwit them as they seek to make a living.

This affords no margin for error for the broad mismanagement of regulators unable to keep up with fishermen who, in the aggregate, will continue to outwit them as they seek to make a living.

Worse, the failure of the central planning model will raise food prices, put fishermen out of work, and possibly lead to the extinction of various species of sea creatures. Like Ahab, then, the central planners are both doomed to fail and certain to drag down others with their failure.

‘Tragedy of the Commons’

Discussions of wild resource management often feature a reference to the 1968 Science article10 by that name from Garrett Hardin. Hardin, an ecologist obsessed with what he saw as human overpopulation, knew how to turn a phrase. The “tragedy” is the name he gave to any resource held in common that is abused.

Regardless of Hardin’s idiosyncrasies, he usefully encapsulated the real concern that confronts resource managers. How should we preserve a resource that must be exploitable, without overexploiting it?

The example most rooted in the history of the last thousand years is common grazing rights in England – where herders are incentivized to add to their herd and deplete the commonly-held grazing fields. Logging can have a similar challenge. If government owns the land and allows logging to take place, companies may attempt to grab all the lumber they can without regard to planting new trees. Hunting on land is also analogous.

Hardin had his own hobbyhorse concern – one of the sections in his six-page essay is “Freedom To Breed Is Intolerable” – suggesting that humans themselves were an unfolding tragedy. He walked his talk, committing suicide with his wife in 2003.

The regulatory death-spiral holds no answers – instead, a new paradigm is needed. Property rights enlist the users, but they require a certain “letting go” on the part of regulators.

Countering Doubts

This ‘Catch Shares’ Thing Sounds Great. What’s the Holdup?

Because there are thousands of fisheries individually administered – not just in the United States, but around the world – catch shares may take decades to be adopted. That means the transition to a catch share system should be as transparent, straightforward, and smooth as possible in order to serve as a model for transitions in other fisheries.

Some of the confusion surrounding catch shares arises out of simple misunderstandings. Florida Republican Rep. Steve Southerland posted an op-ed in The Hill newspaper11 in April 2011 in which he argues catch shares are a bad idea.

Among his points: 1) it would prevent him from hopping in a boat with his sons whenever they liked to catch some fish for dinner; 2) it’s part of a secret plan by the federal government to regulate fishing; and 3) catch shares is a form of cap and trade, and thus analogous to the proposed carbon trading scheme that has become anathema to conservatives and many others.

If catch shares really is a secret federal regulatory plan to impose a cap and trade system to stop Southerland from fishing with his sons, that is indeed problematic. However, fortunately, it is none of those things. How so?

1) Recreational fishing. Southerland’s anecdote about catching fish for his own consumption is covered legally under recreational fishing. Such activity has not been prohibited under any catch share program in the U.S. In fact, all recreational fishing – a fraction of the total – is cordoned off from catch shares. Catch shares applies exclusively to commercial fishing.

To the extent there may be legal ambiguity, it may be productive for future legislation to clarify that such fishing as Southerland describes is recreational and should be legal. However, what must be avoided is any attempt to redefine some commercial fishing as recreational in an attempt to skirt the rules. That would lead to black market fishing that would undermine fisheries management regardless of which system – catch shares or traditional – is in use.

2) Secret federal regulations. It’s not entirely clear why Southerland implies that catch shares would impact his ability to catch fish for his family’s consumption, since this has been the case under no catch shares program ever. The explanation may lie in the bogeyman of the federal regulatory structure; certainly, federal regulators have inflicted plenty of arbitrary and capricious rulemakings over the years. However, it’s way off base to suggest that catch shares are a new regulatory incursion on the fishing industry.

Rather, catch shares allow government to ease the regulatory burden on the fishing industry. This is true both in theory, since fishermen regulate the securing of their own catches, and in practice, since the institution of catch shares has typically featured the lengthening of fishing seasons and other easing.

3) Cap and trade. It is true that catch share programs rely on a “cap” in order to assign value to the quotas for each fisherman. However, the cap has been in place for decades. Indeed, from the very inception of fishing seasons, a cap was in place. The concept of a season automatically implies a cap of some type. It is also true that fish, unlike carbon, is a real commodity that has value outside of a government-constructed regulatory scheme to give it value. That is to say, the demand for fish is real and based on the prices people are willing to pay. The demand for “carbon credits” is zero absent a government mandate.

More recently, regulations have grown in sophistication and data support. The question must be asked: if the “cap” in this case is bad, does that mean there should be no cap at all? It’s not clear that Southerland means to advocate for such a solution.

But the Mechanism for Transitions Must Be Credible

A more tangible concern about transitioning to catch shares is fleet consolidation. In Joseph Schumpeter’s 1942 work, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, he wrote about a process called “creative destruction.” His point was that entrepreneurship would foster economic growth, but that a significant side effect would be the tearing down of established systems and businesses.13

In this case, there is unquestionably a churning in the marketplace created by catch shares. The size of some fishing fleets have shrunk, with catch shares in places such as some Alaskan fisheries being based on performance over several seasons – cutting out some smaller or more recent market entrants. Despite the safer and generally better nature of fisheries under catch shares, some stakeholders express concern about fleet consolidation and the wealth gained by catch shares holders.

There is no easy response to such concerns, except to point out the many fisheries around the world facing total depletion of stocks under traditional, centralized regulatory management. Simply put, traditional management threatens to leave all fishermen out of work, not just the ones without catch shares.

Certainly, the transition to catch shares must be seen as fair and open and not simply a festival of crony capitalism. It also must be understood that the transition may be bumpy at first – the Cape Cod Times in a 2011 article quoted one fisherman with four years’ catch shares experience saying “The first year is the worst year.”14

Conclusion

This May Take Some Time to Sort Out

A challenge in reaching a logical policy goal is the emotional attachment to something as deeply rooted in human civilization as fishing. Many of the concerns have to do with threatening a way of life that has existed for thousands of years.

However, catch shares do not threaten any way of life. Indeed, the real question is how modern market realities – featuring billions of consumers waving hard cash – can be addressed. It is these billions of consumers that have upended the ancient fishing commons.

More immediately, the attachment to the ideal of open fisheries died decades ago under federal management with the institution of fishing seasons and licensing. Barring a more radical suggestion, the best way to uphold market principles and reduce government heavy-handedness is a means of empowering fishermen themselves to manage ocean resources. With catch shares, fishermen will be driven by an Adam-Smith-worthy self-interest to maximize fish production – and the butter and garlic won’t get lonely.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

George Landrith is the president of Frontiers of Freedom, a public policy think tank devoted to promoting a strong national defense, free markets, individual liberty, and constitutionally limited government. Mr. Landrith is a graduate of the University of Virginia School of Law, where he was Business Editor of the Virginia Journal of Law and Politics. In 1994 and 1996, Mr. Landrith was a candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia’s Fifth Congressional District. You can follow George on Twitter @GLandrith.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

End Notes

1 …or battered and fried and served with lemon slices and french fries; diced and served with rice, wasabi, and ginger; or combined with steak for a surf ‘n turf offering. Limitless possibilities.

2 United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, Consumption of Fish and Fishery Products: http://www.fao.org/fishery/statistics/global-consumption/en

3 United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2010: http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/i1820e/i1820e00.htm – page 8 of the document (but page 26 of the pdf at the link). Link via the Competitive Enterprise Institute’s Give a Man a Fish: The Case for a Property Rights Approach to Fisheries Management, May 17, 2012: cei.org/sites/default/files/Iain%20Murray%20and%20Roger%20Abbott%20-%20Give%20a%20Man%20a%20Fish.pdf

4 Monograph from the Mayo Clinic website, retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/fish-oil/NS_patient-fishoil on July 7, 2012.

5 Conversation with a Regional Vice President for Arbonne International.

6 Food Zones Chart retrieved from here: http://www.heartzones.com/store/index.php?main_page=popup_image&pID=366

7 An Ocean Blueprint for the 21st Century: Final Report of the U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy, September 20, 2004: http://www.oceancommission.gov/documents/full_color_rpt/000_ocean_full_report.pdf – page 287 of the document (but page 325 of the pdf at the link). Link via the John Locke Foundation’s Catch Shares: A Potential Tool to Undo a Tragedy of the Commons in NC Fisheries, April 26, 2012: http://www.johnlocke.org/research/show/spotlights/272

8 Projection on our part, with thanks to Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, chapter 36.

9 An Ocean Blueprint, page 287 of the report, page 325 at the link referred to in 6 above.

10 Garrett Hardin, The Tragedy of the Commons, Science Magazine, December 13, 1968. Retrieved from here: http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/reprint/162/3859/1243.pdf.

11 Rep. Steve Southerland (R-FL), “National Ocean Policy: Bad for coastal economies,” The Hill newspaper, April 5, 2012. Retrieved from here: http://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/energy-a-environment/220211-national-ocean-policy-bad-for-coastal-economies

12 Grazing image retrieved from here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tragedy_of_the_commons

13 Schumpeter was actually a pessimist about the ability of the market to sustain creative destruction due to its tendency to erode the support mechanisms that foster entrepreneurship. But in this case, the property rights of fishermen with catch shares give a good foundation for stability, since their individual quotas fall under constitutional protections.

14 Doug Fraser, “Fishermen adapt to new rules,” Cape Cod Times, April 17, 2011, www.capecodonline.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20110417/NEWS/104170326 – Link via the John Locke Foundation paper cited in 6 above.