Milton Friedman on Kennedy’s antimetabole

by Scott L. Vanatter

One of the most well-known lines from presidential addresses was written for John F. Kennedy by Ted Sorenson. Kennedy was not the first president to use a speech writer. Presidents have been using speech writers since the beginning. Alexander Hamilton wrote the first draft of George Washington’s Farewell Address. Washington worked with Hamilton till it said just want he wanted. This is the standard and accepted procedure. Not all Presidents have written as elegantly or effectively as Lincoln.

Note: It is well-accepted that five years before Kennedy was elected president his future presidential speechwriter Ted Sorenson wrote the book Profiles in Courage for which Kennedy (not Sorenson) won 1955 Pulitzer Prize.

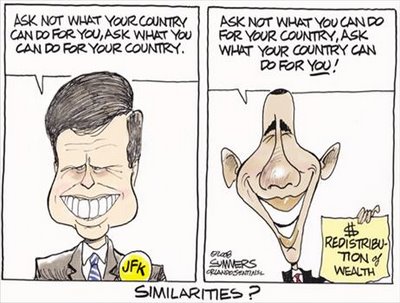

Many school children can quote Sorenson’s ubiquitous, “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.” Many left-liberals have internalized, if not canonized the line. They have infused it with, perhaps, more import and meaning than actually obtains. This short couplet is often cited as an example of chiasmus (inverse parallelism), but it is more accurately described as an example of antimetabole (the repetition of words in successive clauses, but in reverse grammatical order).

There is a strain of left-liberal thought which denies any value in the original intent of the writers of the Constitution. This presents the danger of every generation, every year, every session of Congress having — essentially — a collective, purposeful amnesia. The Founders, even George Washington, often warned that we endanger our rights when we stray from our written and collectively-agreed upon set of understandings. No matter how concrete or nebulous Sorenson’s line is it also can infused with practically whatever meaning one desires.

A simple understanding of the first of the two clauses of Sorenson’s line (“Ask not what your country can do for you”) could be understood as, Do not ask for government benefits. Take care of yourself. (Another interpretation will be offered below.)

A similar understanding of the second of the two clauses (“Ask what you can do for your country”) could be understood as, Be a good neighbor — and pay your taxes. (All your taxes, and on time. And don’t complain!) There are many more nuanced or more brute-force interpretations extant.

As with the sacred literature of any religion, various meanings can be inferred from a given text. Deconstructionism posits that once a writer has penned the words in question, and they are sent out into the world, the words achieve a life of their own. If this can be applied to poems and novels, it can also be applied to politicians’ rhetoric. Sorenson’s line, when dissected, becomes a nonsensical koan (a paradox to be meditated upon).

Rather than accepting Sorenson’s implied mundane levels of faux meaning, let’s take apart his line by examining its base assumptions. Milton Friedman had the following take on the line. This insight served as the opening of Friedman’s classic Capitalism and Freedom:

In a much quoted passage in his inaugural address, President Kennedy said, “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.” Neither half of the statement expresses a relation between the citizen and his government that is worthy of the ideals of free men in a free society. The paternalistic “what your country can do for you” implies that government is the patron, the citizen the ward, a view that is at odds with the free man’s belief in his own responsibility for his own destiny. The organismic, “what you can do for your ‘country” implies the government is the master or the deity, the citizen, the servant or the votary.

Friedman does not twist Sorenson’s saying; he is not unfairly characterizing it. Friedman is accurately describing the obvious assumption inherent in what Sorenson wrote. Friedman continues,

To the free man, the country is the collection of individuals who compose it, not something over and above them. He is proud of a common heritage and loyal to common traditions. But he regards government as a means, an instrumentality, neither a grantor of favors and gifts, nor a master or god to be blindly worshipped and served. He recognizes no national goal except as it is the consensus of the goals that the citizens severally serve. He recognizes no national purpose except as it is the consensus of the purposes for which the citizens severally strive.

Friedman neither wildly nor blithely dismisses Sorenson’s position out of hand. He is carefully describing the core contract which the Founders set out in our Founding Documents. Tying today’s policies and politics to these core principles is how we keep our nation true to the unique vision of the Founders. Friedman continues,

The free man will ask neither what his country can do for him nor what he can do for his country. He will ask rather “What can I and my compatriots do through government” to help us discharge our individual responsibilities, to achieve our several goals and purposes, and above all, to protect our freedom? And he will accompany this question with another: How can we keep the government we create from becoming a Frankenstein that will destroy the very freedom we establish it to protect?

Friedman’s last question about accidentally destroying freedom cannot be ignored. It is the eternal political question. To consider Sorenson’s proposition at face value, without examining its assumptions, is to lose the battle before it begins. In other words, a Frankenstein slowly but surely rises right in front of our eyes — without our seeing it. Even though we are looking right at it. We are like the slowly boiling frog. George Orwell warned that, “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.”

Of course, liberals and much of the mainstream media desire certain electoral outcomes. So much so that they sometimes willingly ignore evidence which works against their desires. Other times they are blinded to these forces; they cannot discern what is happening before their eyes. Yes, this phenomenon can also occur with conservatives. As conservatives are more grounded in logic and evidence, this happens much less to them than with liberals and the mainstream media.

No matter how innocent Sorenson and Kennedy intended it Friedman rejects their sentiment outright. He destroys its convenient assumptions. If we do not evaluate their argument correctly, we are caught in the trap of debating secondary items rather than first principles. Friedman’s model is a good one for evaluating today’s issues. Rather than debate the details of Obama’s propositions — whether they are posited by Pelosi, Reid, or Biden — we need to search deeper and examine their basic assumptions. Only then can we ensure our policies adhere to correct Constitutional principles. Only then we can “form a more perfect union.”

If we start off right it is easy to keep going right. But if we start off wrong, it may be quite a while till we can set right our path.

~

Note: This piece first ran on October 28, 2012.