Over my career, I’ve tended to resist press bashing. Part of the reason for that may be that there are plenty of journalists whose work I respect and whom I’ve come to admire. But I must say that the way the press as an institution covered the 2012 presidential election was in many respects depressing—and in some respects its biases have rarely been more fully on display.

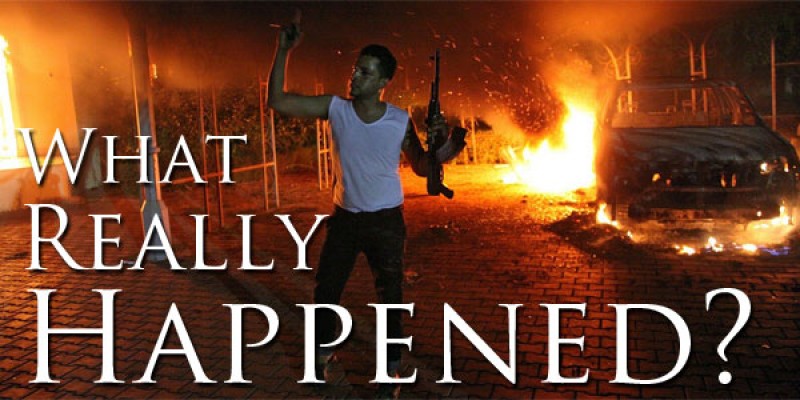

There are a dozen examples I could cite, but let me simply focus on one: The September 11 attack on the U.S. diplomatic facility in Benghazi. We witnessed a massive failure at three different stages. The first is that the U.S. ambassador to Libya, Christopher Stevens, and others asked for additional protection because of their fears of terrorist attacks. Those requests were denied—and Mr. Stevens became the first American ambassador to be murdered in more than 30 years, along with three others. The second failure was not assisting former Navy SEALS Tyrone Woods and Glen Doherty when they were under attack (both were killed). The third failure was that the administration misled the American people about the causes of the attack long after it was clear to many people that their narrative was false.

Yet with a few honorable exceptions—Fox News being the most conspicuous—the press has shown no real appetite for this story. It’s not that it hasn’t been covered; it’s that the coverage has lacked anything like the intensity and passion that you would have seen had this occurred during the presidency of, say, Ronald Reagan or George W. Bush. I have the advantage of having worked in the Reagan administration during Iran-contra and the Bush White House during the Patrick Fitzgerald leak investigation—and there is simply no comparison when it comes to how the press treated these stories. The juxtaposition with the Fitzgerald investigation is particularly damning to the media. Journalists were obsessed by that story, which turned out to be much ado about nothing—Mr. Fitzgerald decided early on there were no grounds to prosecute Richard Armitage for the leak of Valerie Plame’s name—and obsessed in particular with destroying the life of the very good man who was the architect of George W. Bush’s two presidential victories (thankfully they failed in their effort to knee-cap Karl Rove).

In the Benghazi story, we have four dead Americans. A lack of security that borders on criminal negligence. No apparent effort was made to save the lives of Messrs. Woods and Doherty, despite their pleas. The Obama administration, including the president, gave false and misleading accounts of what happened despite mounting evidence to the contrary. And the person who was wrongly accused of inciting the attacks by making a crude YouTube video is now in prison. Yet the press has, for the most part, treated this story with ambivalence and reluctance. A reliable barometer of the views of the elite media is Tom Friedman of the New York Times, who said on Meet the Press on Sunday, “To me, Libya is not a scandal, it’s a tragedy.”

Here’s the thing, though. If the exact same incidents had occurred in the exact same order, and if it had happened during the watch of a conservative president, it would be a treated as a scandal. An epic one, in fact. The coverage, starting on September 12 and starting with Mr. Friedman’s newspaper, would have been nonstop, ferociously negative, and the pressure put on the president and his administration would have been crushing. Jon Stewart, the moral conscience of an increasing number of journalists, wouldn’t have let this story die.

Yet President Obama avoided all of that. Indeed, it was Mitt Romney who incurred the special wrath of reporters for his criticism of a statement made by the American embassy in Egypt after the building was stormed by an angry mob (a criticism, by that way, that the Obama administration agreed with a few hours after Mr. Romney made it). Most reporters—again, with a few impressive exceptions—treated the Benghazi story with nonchalance.

For some journalists, it’s fairly clear as to why: they had a rooting interest in Mr. Obama winning and they carried a deep dislike, even contempt, for Governor Romney. But for many others I think the explanation is more subtle and in some respects more problematic. They appear to be completely blind to their biases and double standards. If you gave them sodium pentothal, they would say they were being objective. Self-examination, it turns out, is harder than self-justification. And of course being surrounded with people who share and reinforce your presuppositions and worldview doesn’t help matters. (A model for today’s reporters is Richard Harwood, a Washington Post reporter who called his editor in Washington, Ben Bradlee, and asked to be taken off the 1968 Robert Kennedy campaign on the day of the California primary because he sensed he was, in the words of RFK biographer Evan Thomas, losing his “newsman’s reserve and … his objectivity.”)

In general, journalists receive critiques like this with indignation. They enjoy holding up public officials, but not themselves, to intense scrutiny. They insist that their personal biases never bleed into their story selection or coverage. But the outstanding ones and the honest ones would admit, though perhaps only to themselves, that the double standard is real and troubling, that it’s injurious to their profession, and that things really do need to change. Perhaps because they still know why they got into journalism in the first place—not for advocacy but to report the news in a relatively even-handed manner, to “speak truth to power,” regardless of the political views of those in power, and to pursue stories in a way that is fair and unafraid.

Today such an attitude sounds almost quaint.

– – – – – – – – – – – – –

Peter Wehner is a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. Previously he worked in the administrations of Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and George W. Bush. In the last of which, he served as deputy assistant to the president. This article was originally published in Commentary.