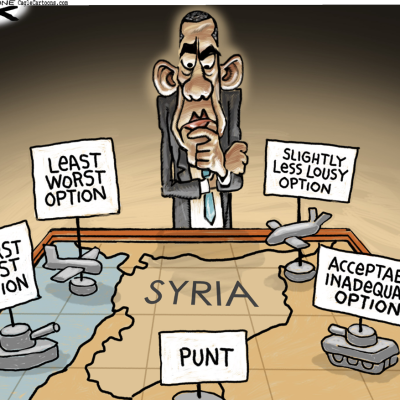

It’s hard to pinpoint just when, exactly, Barack Obama’s Syria policy fell apart. Was it in December, when Islamists humiliated U.S.-backed rebels by seizing what limited supplies America had given them? Was it back in September, when Obama telegraphed his reluctance to enforce his own “red line” after the Syrian regime used chemical weapons on its own people? Was it in the months beforehand, when the administration quietly and mysteriously failed to make good on its pledge to directly arm the rebels? Or did it collapse in August 2011, when Obama called on Syrian dictator Bashar Assad to go, only to do almost nothing to make it happen?

But collapse it has, and more than 130,000 deaths later, the White House is now pinning its hopes on a peace conference in Switzerland later this month that is being billed as the last, best hope for a negotiated solution to a conflict that has displaced a staggering 40 percent of Syria’s total population, some 23 million people, in what the United Nations says is fast becoming the worst and most expensive humanitarian catastrophe in modern history.

Thirty countries, the United Nations, the European Union and the Arab League are all sending representatives to the Jan. 22 conference, where they are expecting to broker a peace accord between Syria’s two warring sides. As it now stands, however, the meeting, known as Geneva II, is already a fiasco. None of Washington’s affiliated rebels has any significance on the ground in Syria any longer, and the rebels who do matter on the battlefield want absolutely nothing to do with the conference; they will not talk with Assad or his state sponsors Russia and Iran, the arms dealers and militia builders who are after all underwriting Assad’s war machine. In the months since Obama’s decision to cancel military retribution for the regime’s Aug. 21 chemical weapons attack in Damascus, we have witnessed the near-total collapse of the U.S.-backed Free Syrian Army (FSA), and with it the last shred of U.S. influence on the trajectory of the conflict.

The president’s indecision played a major role in the FSA’s eclipse. First, Obama deferred the decision on whether to wage punitive airstrikes to Congress. Then he sent high-ranking officials to Capitol Hill to sell this unloved policy of military intervention in a halfhearted and nothing-to-see-here manner, downplaying the effect that the mooted “unbelievably small” airstrikes, as Secretary of State John Kerry termed them, would have on the regime’s war-making ability. Finally, with the votes not forthcoming, the president scrapped the idea altogether in favor of an 11th-hour plan offered by Russian President Vladimir Putin to decommission Assad’s chemical stockpiles. From there, what remained of the FSA quickly disintegrated.

But the seeds were sown months earlier. About a week after Kerry gave two rousing war speeches and compared Assad to Adolf Hitler, and just days after Obama announced that he’d be seeking congressional authorization for airstrikes, the Wall Street Journal reported what every Syrian already knew: The light arms that the White House had licensed the CIA to deliver the FSA’s coordinating body, the Supreme Military Council (SMC), way back in June—when earlier evidence of the regime’s repeated use of chemical weapons had become internationally known—had yet to arrive, owing to the difficulty of securing delivery “pipelines.”

The Journal account suggested what now seems clear: The administration didn’t want the rebels to actually win (this was “somebody else’s civil war,” as Obama would later phrase it) or for any direct U.S. intervention to fundamentally alter the balance of power on the ground. It only wanted to run arms to persuade the FSA to buy into its negotiating strategy. “When we have more skin in the game,” one unnamed senior administration official told the Journal, “it just puts us in a position to have deeper relationships with the opposition but also work more effectively with other countries who are doing a lot in terms of support.” Instead, the White House took all its skin out of the game; and those other countries, chiefly Saudi Arabia, turned ferociously against the United States, with potentially dangerous consequences to come.

It did not take long for al Qaeda to smell an opportunity.

Ayman al-Zawahiri, the group’s successor to Osama bin Laden, was the first to sense most keenly Obama’s wobbliness on Syria and the deleterious impact that a deferred U.S. attack on Assad would have on FSA morale and credibility. In his address on the 12th anniversary of 9/11, Zawahiri denounced the FSA for the first time as “enemies of Islam” and agents of a U.S.-backed program for fomenting a Sunni “awakening,” or sahwa, which he defined as a hearts-and-minds strategy designed to isolate and defeat al Qaeda, just as tribal leaders and coalition forces had done half a decade ago in Iraq.

But in Syria, there are now two al Qaeda affiliates or offshoots. The strongest is the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS), by far the more brutal and uncompromising of the two. The man in charge of ISIS is Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, an Iraqi who claims to be a direct descendant from the Prophet Mohamed and is clearly running one of the most expansive and successful jihadist campaigns in the Middle East. Baghdadi sent operatives into Syria in the summer of 2011 who created Jabhat al-Nusra, which began carrying out suicide bombings throughout the country and was blacklisted by the United States in late 2012. However, Nusra split with ISIS last year owing to tensions between Baghdadi and Nusra’s own leader, Abu Muhammad al-Jawlani. (Zawahiri sided with Jawlani and tried in vain to rein in Baghdadi, now relocated from Iraq to Syria.) In the last several months, ISIS has emerged as the more powerful faction, having absorbed a great deal of Nusra’s fighters. According to an intelligence briefing prepared by the SMC, the “most dangerous and most important” section of the organization “consists of approximately 5,500 foreign fighters.”

It was ISIS that went to war with the FSA. A day after Zawahiri’s communiqué, on Sept. 12, it launched a campaign known evocatively as “Expunging Filth” and aimed at the U.S.-backed al-Farouq and al-Nasr brigades in northern Syria. ISIS had already killed Kamal Hamami, an SMC commander, in July after a dispute at one of the group’s checkpoints in Latakia, but now it took to executing another SMC rebel on charges of trying to precipitate sahwa. But the starkest expression of this internecine warfare came about a week later, on Sept. 18, when ISIS violently raided the northern town of Azaz, which lies strategically south of a main border crossing between Syria and Turkey through which “non-lethal” Western aid had been delivered to SMC groups.

One of these groups, the Northern Storm Brigade, which hosted Sen. John McCain in Syria last May, was expelled from Azaz by the jihadists. Panicked and outmatched, Northern Storm called on Liwa al-Tawhid, a nominally SMC-aligned Islamist “super-brigade” in Aleppo, to come to its rescue. Tawhid is, or was, a pragmatic Islamist militia known for being open to greater Western support, if only such had ever been forthcoming, and also one of the largest rebel formations in Syria, with an estimated 12,000 fighters. Tawhid heeded Northern Storm’s call for help and dispatched forces to Azaz to try to calm a chaotic situation. Meanwhile, an intense debate broke out among Tawhid’s commanders, as several rebels informed me at the time, about whether or not to use the Azaz takeover as an opportunity to declare all-out war on ISIS or to mediate the crisis through negotiations.

In the end, the border crossing was returned to the FSA, but Azaz wasn’t. And the damage was done. After this incident, and following further ISIS gains throughout northern and eastern Syria, more and more FSA-aligned fighters, sometimes even whole brigades, began defecting to the al Qaeda franchise. Areas where the FSA had once had strong presences, such as Binnish, Dana and al-Bab — a town I visited in late July 2012 under FSA escort, days after it had been liberated from regime control — now fell to ISIS.

By this time, too, many rebels were coming to the realization that by allowing foreign extremists into Syria in the absence of Western intervention, they had inadvertently laid the groundwork for a totalitarian counterpart to the regime, one that tolerates no dissent and has kidnapped journalists, activists and a popular Jesuit priest, and staged public beheadings of its enemies. When I interviewed FSA fighters, including Islamists, in southern Turkey in mid-September, their common refrain was that they now faced two mortal enemies. “Bashar al-Assad is beautiful compared to the Islamic State,” one rebel aligned with the SMC told me at the time.

Not coincidentally, on Sept. 24, well after the threat of U.S. airstrikes had receded, the best-equipped and most battle-hardened Islamist groups in Syria then took to angrily denouncing the U.S.-backed political opposition in exile, the Syrian National Coalition (SNC), rejecting democracy and secularism and stating that Islamic law was the sole course for a post-Assad state. Whether this was undertaken out of genuine conviction or fear of being added to al Qaeda’s ever-expanding kill list is open to interpretation. But after the United States backed away from attacking the regime, any rebel doubting the wisdom of aligning with Washington now had cause to move in an objectively anti-American direction. Obama’s deal with Putin only encouraged this tendency.

On Sept. 28, the United Nations Security Council unanimously adopted its first binding resolution on Syria, calling for the total dismantlement and destruction of the regime’s chemical weapons program. Several analysts at the time, including your humble servant, predicted that this resolution would only re-legitimize Assad as a necessary partner of the West in an ambitious, year-long de-proliferation program, thereby driving an even deeper wedge between the U.S.-led “Friends of Syria” group of more than 100 countries and the already angry, disillusioned and shrinking FSA. Our warnings went unheeded. U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon lauded the accord as “historic” and the “first hopeful news on Syria in a long time,” while cautioning that it was not, for the regime, a “license to kill with conventional weapons.” Kerry claimed that the resolution proved “diplomacy can be so powerful that it can peacefully defuse the worst weapon of war.” Mark these words carefully.

September then drew to a close with another major rebel development. On the 29th, 50 Islamist units in and around Damascus united to form the Army of Islam, led by the toughest brigade of the bunch, Liwa al-Islam, which hitherto had been nominally associated with the pro-Western SMC. Based primarily in East Ghouta, the same area of Damascus that was gassed on Aug. 21, Liwa al-Islam is headed by Zahran Alloush, who now became the leader of the Army of Islam. A prominent Salafist and former inmate of Syria’s Sednaya prison, which has come to be known as a “university” for graduating Islamic fundamentalists, Alloush was released under Assad’s “amnesty” program in 2011, which many Syrians believe was designed to satisfy regime propaganda about the opposition’s true ideology. Alloush has thrived thanks in part to his close and extensive ties to Saudi Arabia: His father is a well-known cleric in Medina and his brother also lives in the Gulf kingdom. Yet he’s also been outspoken in his hatred of the SNC — which is headed by a Saudi appointee, Ahmed Jarba—and dismissive of the SMC and its Western-supplied aid, which Alloush has deemed negligible.

Even still, attempts at reconciliation with the U.S.-backed opposition were made. Sometime in October, the Army of Islam started negotiating with the SMC about a prospective merger and expansion of the latter’s command structure. According to well-placed rebel and diplomatic sources, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey were uncharacteristically united on one point: that Gen. Salim Idris, the embattled and luckless chief of staff of the SMC, in whom the United States has invested its hopes for a credible and relevant client, should remain in his post in the reconstituted organization. Riyadh’s current intelligence chief and national security advisor, Prince Bandar bin Sultan, was also said to have pressured several private Saudi financiers to support this consolidation effort—probably owing to rumors that the United States might blacklist the Army of Islam in whole or in part if it refused to subject itself to U.S. control. But the talks quickly foundered. For one thing, Alloush and Idris hate each other and yet were set to become de facto equals on the same rebel supervisory council. Alloush also refused to recognize the SNC, the political arm of the SMC, and apparently asked for too many seats for his own Army of Islam representatives.

So, instead, a different rebel merger took place. On Nov. 22, the Army of Islam announced that it was joining with several other Islamist or Salafist sub-groupings—many of them also nominal affiliates of the SMC—to form a new entity known as the Islamic Front. The resulting mega-militia would thus become the largest consortium of anti-Assad fighters on the ground in Syria, with estimates varying between 45,000 and 60,000 fighters. The leading hardline Islamist formations signed up immediately, among them Liwa al-Tawhid (of the Azaz affair), Suqoor al-Sham and Ahrar al-Sham, a powerful Salafist brigade ideologically close to al Qaeda and heavily financed by Kuwaiti clerics and sheikhs. Noticeably excluded were ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra, prompting speculation that the Saudis were finally looking to isolate al Qaeda in Syria. Alloush became the front’s chief of military operations, and Hassan Abboud, the commander of Ahrar al-Sham, became its chief political officer. Several top-level Syrian Sunni clerics immediately threw their support behind this new collective enterprise.

And so did the Islamic Front’s biggest foreign patron, in a manner the United States never even thought about doing with the FSA. According to a newly published anatomy of U.S. policymaking in the Wall Street Journal, which cites Obama administration officials, Washington’s objective in arming and training rebels “wasn’t so much to help [them] win as to assuage allies who thought the U.S. wasn’t engaged.” Yet this limited approach failed on two levels: Not only did it destroy the West’s nominal proxy in Syria, but it also compelled Riyadh to “step outside the umbrella” of U.S. oversight altogether and plot the construction of an overshadowing Islamist counterpart army.

The formation of the Islamic Front presents Washington with an exquisite dilemma. It is now the most powerful grouping of rebel brigades in Syria. But according to its charter, it opposes man-made laws and democracy and believes in a nebulously defined “Islamic state” for Syria. Its primary objective is the “toppling of the regime” and the abolition of Assadist state institutions, from the security services to the military. It does not rule out cooperation with external countries so long as these do not behave inimically to the front’s interests and objectives. But the Front considers treasonous any negotiation with the regime, punishable by trial in a sharia court. All of the above is diametrically opposed to longstanding and articulated U.S. policy goals for Syria, which are premised on negotiations and the preservation of core regime institutions.

The United States has nonetheless already attempted to test the waters with Alloush and his new army. On Dec. 3, the Wall Street Journal reported that some of the constituent brigades that now form the front had been talking to American and European officials in recent weeks. The goal? “[T]o persuade some Islamists to support a Syria peace conference in Geneva on Jan. 22, for fear that the talks won’t yield a lasting accord without their backing,” the Journal reported. This is a very well placed fear given that the front represents a sizable contingent of all rebels in Syria, without which any chin-wag or inked deal in Geneva instantly becomes an exercise in futility.

So now the Front, still in its infancy, faces a dilemma of its own. Attendance at the conference constitutes an act of treason according to its own declared definition of the term. And even if it were flexible, working with Washington to parlay with Damascus for a “political solution” is sure to end whatever tenuous arrangement Alloush has made with the jihadist ultras of ISIS. It might even risk the front’s metamorphosis into another outright “enemy of Islam” and invite crippling al Qaeda attacks.

In fact, the Front has already taken to dramatic acts to explain loudly and clearly to the Obama administration what it thinks about collusion with the West or rapprochement with Assad. At midnight on Dec. 7, about 60 armed fighters from Jabhat al-Nusra, some wearing explosive suicide vests, raided the First Battalion of the SMC in the al-Waqi mountain near Atmeh, a town just across from the Syrian-Turkish border. By issuing the threat of a violent takeover, but without firing a shot or exploding any munitions, these fighters assumed control over the battalion’s warehouse. Upon hearing of the seizure, the SMC, in a sad replay of the Azaz incident from September, asked the Islamic Front to come to its aid and send reinforcements at another strategic location—SMC headquarters—to protect against an impending Nusra attack. Alloush himself arrived with fighters at around 1 a.m. But, rather than offer reinforcements, they took possession of all SMC complexes and warehouses in Atmeh and commandeered all supplies contained therein including food, medical kits, communications equipment and vehicles. Also in supply were some light arms and ammunition. Alloush moved the guns and bullets to a nearby front headquarters as the Islamic Front flag was raised over the SMC buildings. Alloush is reported to have told the SMC personnel not to worry—they weren’t under threat of assault, they were simply under new management. An inventory of all American-run goods was then taken. Later that morning, Dec. 7, SMC fighters were evicted from their own premises. (This sequence of events was given to me by the Syrian Support Group, a Washington-based NGO licensed to send non-lethal supplies to the SMC.)

Responding to this fresh embarrassment, the Obama administration did what little it could. On Dec. 11, the State Department “suspended” its delivery of non-lethal supplies to the SMC. It provided no insight as what actually happened at these facilities on Dec. 7 and may not even know the full story yet. (I spent the better part of a week in December compiling the above sequence of events from various rebel sources, and cross-checking claims to ensure accuracy.) SMC spokesman Louay Mekdad, meanwhile, claimed that the entire contretemps was just a misunderstanding and that the United States had acted prematurely in cutting supply lines.

A day later, however, Salim Idris, the FSA’s top general, told CNN that the suspension of aid was sensible because “[i]t is very difficult now to pass the support to the right hands.” (The Wall Street Journal had reported that Idris was present at SMC headquarters during the seizure and then fled in disgrace all the way to Doha, but rebels close to Idris say that he was in Antakya at the time of the raid and traveled to Qatar for a prescheduled trip.) Dan Layman, a spokesman for the Syrian Support Group, told me that the Islamic Front has now returned two of the confiscated warehouses, but still insists on guarding these and all other raided SMC buildings in Atmeh. Yet there is no indication that the United States has resumed running any aid to the SMC.

Despite these rather inauspicious beginnings, the White House still evidently believes it can tame the Islamic Front into acceding to U.S. demands on diplomacy. On Dec. 12, the Washington Post reported that Washington remains open to expanding the SMC to include front representatives. An unnamed U.S. official told the newspaper, “We don’t have a problem with the Islamic Front,” while describing negotiations as a “work in progress.” If only.

On Dec. 18, the U.S. envoy for Syria, Robert Ford, recently arrived in Turkey for high-level talks with the Syrian opposition, regretted to inform Al-Arabiya, “The Islamic Front has refused to sit with us without giving any reason.” In fact, a rebel in the Front had given a very good reason to Reuters days earlier, explaining that tensions with ISIS had already risen—there have been mutual hostage-takings—since Alloush decided to engage the United States via intermediaries. This is exactly the self-defeating outcome, in other words, that the front had hoped to avoid at its inception.

We now know more about the exact nature of U.S. overtures. As reported by Josh Rogin of the Daily Beast, a high-level White House meeting in early December determined that it wasn’t even Ford who met with front representatives but rather the deputy director of the State Department’s Syria desk. This unnamed official was dispatched with “three specific talking points,” according to Rogin. The first was to persuade the front to attend Geneva II, the second was to ask it to return the SMC’s seized warehouses (something which it has partly done already) and the third was to relay America’s newest “red line” against any rebels working with Nusra or ISIS. There was no indication that the United States was offering anything in return for the front’s satisfaction of these conditions, and anyway, Alloush and Abboud evidently decided not to bother attending.

This decision was very likely either prompted or accepted by the front’s principal backer—Saudi Arabia. On Dec. 15, Saudi Prince Turki al-Faisal, the brother of the foreign minister, pasted the Obama administration for its past and future designs in the Middle East, labeling its response to the Syria crisis as bordering on “criminal negligence.” Having offered nothing to the opposition, Prince Turki said, Washington now demands everything. “The aid [the U.S.] is giving to the Free Syrian Army is irrelevant,” the well-connected royal told the Wall Street Journal. “Now they say they’re going to stop the aid: OK, stop it. It’s not doing anything anyway.” As if to prove his point, the front has already showcased what it can accomplish without so much as a single U.S.-requisitioned weapon. On Monday, Dec. 16, the group lifted an almost month-long media “blackout” on a major offensive it had been waging in East Ghouta, Damascus. Not coincidentally, this offensive began on Nov. 22, the same day as the group’s announced formation. The front claimed that as many as 800 regime soldiers or proxy fighters had been killed and plenty of materiel (including tanks and armored vehicles) had been destroyed or confiscated across some 40 kilometers of now “liberated” territory in the capital district. The fact that thousands of Islamist fighters managed to keep their mouths shut and their YouTube accounts quiet for a full three weeks about a sensitive campaign in Syria’s capital bespeaks a level of command and control that the FSA never came close to exhibiting. Alloush controls his men; Idris barely knows who his are anymore.

Capping off a hectic week in America’s obsolescence in Syria, a mere 24 hours after the front’s media blackout was lifted, the Saudi ambassador to London, Mohammed Bin Nawaf Bin Abdulaziz al Saud, published a blistering op-ed in the New York Times stating that current Western policies “on both Iran and Syria risk the stability and security of the Middle East.” The kingdom, he wrote, transforming Prince Turki’s previous disdain into programmatic action, “has no choice but to become more assertive in international affairs: more determined than ever to stand up for the genuine stability our region so desperately needs… We will act to fulfill these responsibilities, with or without the support of our Western partners.” And they will “continue on this new track for as long as proves necessary.”

Riyadh sees the crisis not just as about Syria but about Iran, whose influence in the Syrian war is viewed by the Saudis as a dire extension of its reach across the Levant. For the Saudi monarchy, this isn’t just a “strategic setback” or a “national security challenge”—it’s nothing short of an existential threat to Sunni Islam. This is why, for instance, Saudi Arabia just announced a $3 billion grant to the Lebanese Armed Forces—for weapons to be purchased from France, another U.S. ally fed up with American bumbling on Syria—as a check against Hezbollah’s military prowess.

But more worrisome is the fact that the Saudis’ dead-serious retrenchment with the Islamic Front doesn’t appear to have penetrated at all in 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

As for the Islamic Front, analysts are divided on the true intentions of the Saudis’ new proxy force. Some believe it is designed to isolate but not antagonize ISIS and possibly also attract less ideological fighters from Nusra who originally joined the group because it was seen as the most capable, well-armed and disciplined in Syria. The reasoning here is that the Front’s Gulf patrons are looking to weaken the jihadists by creating a credible alternative to them. Other analysts have argued that only the narcissism of tiny difference separates the Islamic Front from the jihadists. The main distinction, according to this assessment, is that the Front’s ambitions appear to end at Syria’s borders whereas Nusra and ISIS are committed to exporting jihad and establishing a transnational caliphate.

Whatever the case, the Front and Nusra have partnered in military operations against the regime throughout the month of December, including an ambitious, weeks-long assault on a hospital in Aleppo. So if the Front holds any promise for Western objectives at all, it is that unsavory but somewhat flexible Islamists might eventually eclipse in power and prestige truly radioactive terrorists. But there is hardly any guarantee that Saudi Arabia can accomplish this task unilaterally. The U.S. surge in Iraq, after all, required 20,000 additional soldiers to a garrison of around 160,000, and untold millions in cash bribes to lure Sunni tribesmen away from al Qaeda.

But more worrisome is the fact that the Saudis’ dead-serious retrenchment with the Islamic Front doesn’t appear to have penetrated at all in 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. The very day the ambassador’s editorial ran in the Times, Reuters reported that Obama had again backed down on a former non-negotiable demand for Western diplomacy. American officials, it was reported, have now allegedly instructed senior SNC members that Assad’s ouster as president is no longer either a precondition for Geneva II nor a likely result of the conference. The State Department described the Reuters story as “patently false,” though this will do little to convince rebels who were already prone to thinking that Washington is in league with Damascus.

Islamic radicalism in Syria poses the top threat to U.S. national security, Michael Morrell, then the deputy CIA director, said in August. While this may be true today, it is also not coincidentally exactly what Assad wanted the United States to believe was true in March 2011, when the revolution began. The fear of a once mainstream rebellion turning sectarian and extremist—serially trotted out by American policymakers as a justification for not intervening in the conflict earlier—has now been realized in the absence of any real or meaningful intervention.

Even the one “victory” the administration has claimed — its chemical disarmament plan co-brokered with Putin —is proving to be a devil’s bargain.

On Dec. 12, the State Department issued a statement “condem[ning] in the strongest possible terms the recent massacres of Syrian civilians in the Qalamoun region and elsewhere. Scores of civilians, many of them children, have again fallen victim to brutal violence…. We have long said that those responsible for perpetrating atrocities in Syria—especially the latest vicious violence against innocent civilians—must be held accountable.”

What the State Department did not mention is that the villages and towns where these atrocities have taken place—courtesy of Syrian warplanes, rockets, artillery shells and ground assaults by army regulars and Iranian-trained Shia militias, including Hezbollah— are all located off the main Damascus-Homs motorway. That road has been designated by the regime and by the U.N. as a necessary thoroughfare for transporting more than 1,000 tons of chemical agent and precursor out of Damascus and its outlying suburbs and to the Port of Latakia, where these materials are meant to be loaded onto a Danish-Norwegian flotilla and eventually transferred to a U.S. ship for their destruction at sea. It’s a journey that stretches some 300 kilometers through contested or rebel-held territory featuring plenty of al Qaeda militants, which is why the United States, Russia, China and other countries are outfitting the regime with armored vehicles, geonavigation devices and decontamination equipment. Any interdiction of or attack on a single convoy along this route could be catastrophic, as chemical weapons experts have noted with a mounting sense of alarm commingled with incredulity at the international community’s apparent calmness about the task that lies ahead and that must, according to Resolution 2118, be totally completed by mid-2014.

The first deadline for partial stocks’ removal to Latakia was Dec. 31. It was missed, and those Danish and Norwegian ships meant to receive them turned around and headed back to Cyprus. The next big deadline is early February, but, as one European diplomat recently told the New York Times, “I don’t think any of us really knows how big the delay is likely to be.”

In a background briefing with journalists held last month on the viability of removing Syrian chemical stocks safely from an active war zone — something never before attempted in the history of disarmament schemes — a senior U.S. defense official affirmed that the regime has “a lot of responsibility for getting the materials safely delivered…. Obviously it’s a challenging environment and they’re working through that and taking security into consideration every day as they develop that.”

In effect, the United States is encouraging the regime to defeat the rebels along the delivery route whether they are the U.S.-backed FSA, the Saudi-backed Islamic Front or the al Qaeda affiliates Nusra or ISIS. Then, once defeated, Washington will condemn the way the regime goes about its business, which inevitably involves dropping incendiary bombs from warplanes and helicopters and massacring scores of civilians, many of them women and children. So much for Ban Ki-moon’s denial of a “license to kill” or Kerry’s pronouncement that the “worst weapon of war” can be defused “peacefully.” And the State Department wonders why the Islamic Front won’t even turn up for a meeting.

All of this was avoidable. Even after the Aug. 21 chemical attacks, there were still conspicuous rebels willing to cast their lot with the United States. Their logic was simple: Surely after psychopathically gassing hundreds of people in his own capital city, Assad had motivated even a reluctant and war-weary Barack Obama to hasten his removal. I met and interviewed dozens of such fighters in Antakya, Turkey, in that fateful week when the administration instead announced that it had brokered a deal with the Kremlin. There was now a sense of finality in the air; enough was enough.

From a Western vantage, it may be hard to understand how much these rebels have sacrificed for this waiting-for-Godot strategy. They’ve risked death not only at the hands of the regime and its Iranian-built proxies, but also at the hands of al Qaeda. Now they’re obsolete to everyone except the United States, which only wants them as a catspaw to do another deal—this one with Assad.

Almost comically, Washington has gone, in the last two and a half years, from demanding of an atomized but fairly moderate collection of Syrian rebels that they lower their expectations in exchange for a minimal level of badly needed material support to demanding of a well-organized group of hardline Islamist rebels that they lower their expectations in exchange for minimal levels of totally unnecessary support. To whom is this an intelligent or wise policy?

For months now, U.S. officials have mouthed a mindless catechism: “There is no military solution to the conflict.” To this can now be added that Assad is here to stay and that the real challenge ahead is getting everyone to work together to defeat al Qaeda.

Yet Saudi Arabia and the Islamic Front have plainly got other plans as Robert Ford and John Kerry prepare for their long-awaited waste of time in the Alps.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .