“Clerisy” class does the bidding of tech oligarchs to detriment of the middle class.

by Glenn Harlan Reynolds • USAToday

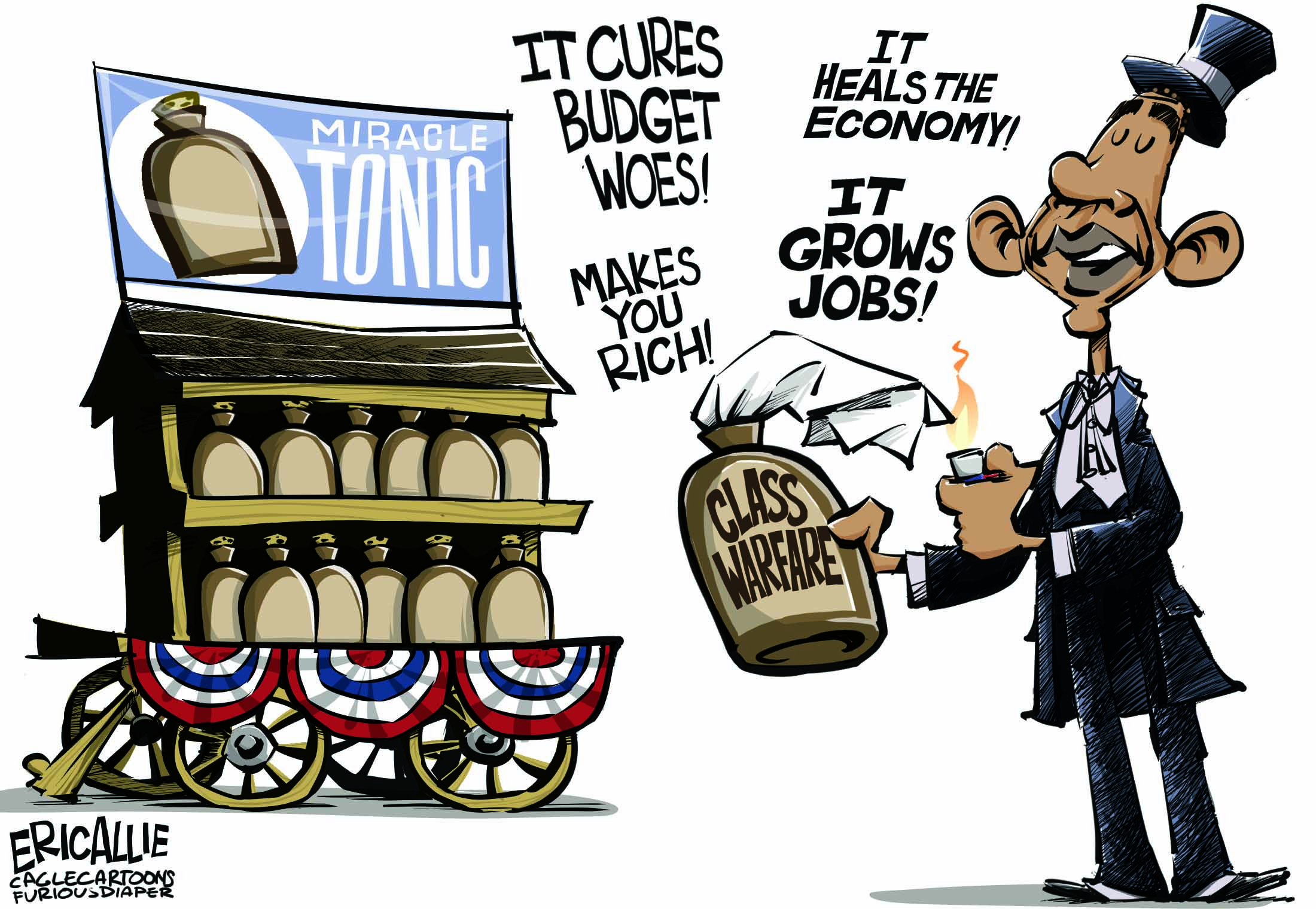

We’ve heard a lot of election-year class warfare talk, from makers vs. takers to the 1% vs. the 99%. But Joel Kotkin’s important new book, The New Class Conflict, suggests that America’s real class problems are deeper, and more damaging, than election rhetoric.

We’ve heard a lot of election-year class warfare talk, from makers vs. takers to the 1% vs. the 99%. But Joel Kotkin’s important new book, The New Class Conflict, suggests that America’s real class problems are deeper, and more damaging, than election rhetoric.

Traditionally, America has been thought of as a place of great mobility — one where anyone can conceivably grow up to be president, regardless of background. This has never been entirely true, of course. Most of our presidents have come from reasonably well-off backgrounds, and even Barack Obama, a barrier-breaker in some ways, came from an affluent background and enjoyed an expensive private-school upbringing. But the problem Kotkin describes goes beyond shots at the White House.

In a nutshell, Kotkin sees California, once again, in its role as an indicator of where the nation is headed. And it’s not an attractive destination.

Once a state where the middle class reigned supreme, the apotheosis of the American Dream, California now has the wealth distribution — and, in some disturbing ways, the political underpinnings — of a Third World country. In Silicon Valley, a group of super-wealthy tech oligarchs live lives of almost unimaginable wealth, while only a few miles away, illegal immigrants live in squalor.

The oligarchs feel free, and even entitled, to choose the direction of society in the name of a greater good, but somehow their policies seem mostly to make the oligarchs richer and more powerful. Meanwhile, once-prosperous middle-class communities, revolving around manufacturing industries that have now moved overseas, either sink into poverty or become gentrified homes for the lower-upper class. The middle class itself, meanwhile, is increasingly, in Kotkin’s words, “proletarianized,” with security vanishing and jobs moving downscale.

The oligarchs are assisted in their control by what Kotkin calls the “clerisy” class — an amalgam of academics, media and government employees who play the role that medieval clergy once played in legitimizing the powerful, and in implementing their policies while quelling resistance from the masses. The clerisy isn’t as rich as the oligarchs, but it does pretty well for itself and is compensated in part by status, its positions allowing even its lower-paid members to feel superior to the hoi polloi.

Because it doesn’t have to work in competitive industries, the clerisy favors regulations, land-use rules and environmental restrictions that make things worse for businesses — especially the small “yeoman” businesses that traditionally sustained much of the middle class — thus further hollowing out the middle of the income distribution. But the lower classes, sustained by government handouts and by rhetoric from the clerisy, provide enough votes to keep the machine running, at least for a while.

This process has gone very far in California, but it’s well underway across America. As the Federal Reserve noted last week, despite a booming stock market and several years of “recovery,” most Americans aren’t doing well. In fact only the top 10% saw their incomes rise between 2010 and 2013.

One reason is that America’s labor market, once famously flexible, has been rendered much less so. As The Economist notes, stifling occupational regulations make it harder for people, especially at the bottom of the economic ladder, to find jobs: “The spread of occupational licensing, for everything from horse massage to hair braiding, has raised barriers to entry for occupations that once required little or no training.”

Those most affected are the young, the poor, and the unemployed. Meanwhile, members of Kotkin’s “clerisy” find work teaching in schools needed for licensing, and in enforcing the licensing programs.

And as Radley Balko notes in the Washington Post, a thicket of petty regulation helps to keep the poor, poor. Traffic fines, fines for not using a city-approved garbage service, even parking tickets all provide revenue for municipal machines that support jobs for the clerisy — social workers, police, etc. — even as they make it harder for poor people to keep their heads above water, or find the kind of work that would let them rise above poverty.

Kotkin is not as pessimistic as this summary suggests. He thinks that America has a vast latent capacity to adapt, and to change the rules democratically, as we’ve done in the past. But, he says, “the most fundamental challenge facing the U.S. is the growing disenfranchisement of the middle and working class from the benefits of economic activity.”

Some people — like the Institute for Justice, a public-interest law firm that addresses absurd occupational licensing rules — are working on addressing that. But if the middle class is to have a future in America, we need to return power to it, at the expense of oligarchs and their secular clergy. Given that the uppermost strata of American society are still doing fine, expect the impulse for change to come from somewhere else.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Glenn Harlan Reynolds, a University of Tennessee law professor, is the author of The New School: How the Information Age Will Save American Education from Itself.