I recently had a conversation with an intensely conservative businessman whose first foray into politics was fighting for a tax hike on his business and others like it. The little town where he lived as a young man had no paved roads, waterworks, or sewage facilities, and the men who had the most invested in the town knew that it needed these to grow, which of course it did. That’s part of what Barack Obama and Elizabeth Warren are referring to with their “you didn’t build that” rhetoric, though they draw the wrong conclusions. They are also sometimes wrong in the specifics, too: The gentleman I was speaking with organized a few other businessmen to install streetlights at their own expense, with the understanding that the town fathers would pay them back when they could afford it. If you’re looking for an example of how small government is good government, a handshake deal to put in streetlights is a pretty good one. That is government at a scale that people can control, manage — and keep an eye on.

It is important to keep government small, but scale is not the only concern: Even the pettiest bureaucracy can descend into indolence and corruption. We talk a great deal about the level of government spending, but pay relatively little attention to a much more basic concern: It matters — a great deal — what government spends that money on. Even the wooliest anarcho-capitalist must look with some sympathy and admiration upon the small-scale model of township government that once characterized New England and the West. “But who will pave the roads?” is a standing libertarian punchline (“The federal government spends enormous sums of money getting monkeys addicted to cocaine, the police have murdered your puppies — But who will pave the roads?”) and, as noted in a certain volume of political speculation, the first paved intercity road in these United States was in fact privately built, suggesting that private enterprise is more than capable of road-making. But it was as a matter of history largely governments that paved the roads, built the sewage systems, drained the swamps, etc. And there was a time when governments, particularly at the local level, did a pretty good job of it.

There was more room for them to experiment in an era in which the federal government did relatively little. At the end of the 19th century, the largest single federal expense was veterans’ pensions, which accounted for nearly half of federal spending. As James Carafano notes, that pension system was a swamp of Republican graft, the original dependency agenda; but in real terms, the money lost to graft today in programs such as Medicare and Medicaid probably would have paid for all of the operations of the federal government in the late 19th century, with a surplus. So easy and profitable is Medicare fraud that New York’s Bonanno mafia clan set up a Florida operation specifically for that purpose. (Florida is the Augean stables of Medicare fraud.) Some of the graft is explicitly criminal, but much of it is perfectly legal: subsidies for cronies, sweetheart loans and generous tax treatment for politically connected businesses, etc. The Solyndra debacle may not have been a crime, but it was criminal.

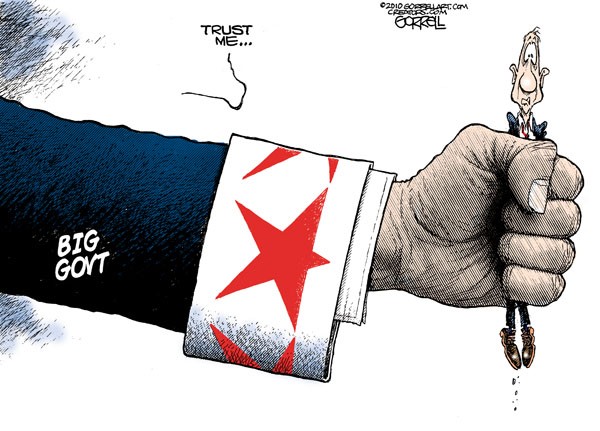

Big government, big expenses, big corruption — big problem.

On the one hand, we have the small-town entrepreneur yearning for sidewalks and streetlights; on the other, we have dodgy “Five Aces” federal contracts and Al Gore’s federally enabled greenmongering. Between those two points there exists a spectrum of possible configurations of government, and the fundamental political debate of our time is whether we’re on the right side of that spectrum or the wrong side. Conservatives want to prune back the vines, and progressives want them to grow thicker.

How’s that working out in the laboratories of the Left?

Progressives argue that we need deeper government involvement in the economy in order to assuage the ill effects of economic inequality. But, as Joel Kotkin points out, inequality is the most pronounced in places where progressives dominate: New York City, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago. The more egalitarian cities are embedded in considerably more conservative metropolitan areas in conservative states. “Part of the difference,” Mr. Kotkin writes, “is the strong growth of higher-paid, blue-collar jobs in places like Houston, Oklahoma City, Salt Lake, and Dallas compared to rapidly de-industrializing locales such as New York, San Francisco, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Even Richard Florida, the guru of the ‘creative class,’ has admitted that the strongest growth in mid-income jobs has been concentrated in red-state metros such as Salt Lake City, Houston, Dallas, Austin, and Nashville. Some of this reflects a history of later industrialization but other policies — often mandated by the state — encourage mid-income growth, for example, by not imposing high energy prices with subsidies for renewables, or restricting housing growth in the periphery. Cities like Houston may seem blue in many ways but follow local policies largely indistinguishable from mainstream Republicans elsewhere.” In Detroit, Chicago, and Philadelphia, African Americans earn barely half of what whites earn — and in San Francisco, African Americans earn less than half of what whites earn. Hispanics in Boston earn 50 percent of what whites make; but it is 84 percent in Riverside County, Calif., a traditional Republican stronghold (it holds the distinction of being one of only two West Coast counties to have gone for Hoover over FDR and is Duncan Hunter’s turf), and the figures are comparable in places such as Phoenix and Miami.

Progressivism is a luxury good for college-educated white people. It is the Hermes sneaker of political tendencies. California is not an especially wealthy state — its median income is right between Wyoming’s and Nebraska’s — but it is a state in which one needs to be pretty well off to live decently. The value of the median home in San Francisco is more than ten times the median income; in San Jose, it’s nine and a half times the median income; in Houston, it’s only four times the median income. California is a great place to be a technology executive or a screenwriter, but it’s a rotten place to be a truck driver. California-style progressivism is oriented toward serving the needs of rich people in San Jose, not those of middle-class people in Riverside County or poor people in the agrarian villages. If you’re a well-off lawyer in the gilded suburbs of Los Angeles, you have a great selection of poor, brown gardeners and housekeepers to lessen life’s burdens, which is great for you but stinks for them. It is not an accident that our nation’s most segregated cities are mostly strongholds of the Left: New York, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Chicago, Milwaukee, Cleveland, Boston.

But the fact is that, despite the po-faced rhetoric, progressives do not really care about the poor, the brown, the black, or the marginalized. Progressivism is very little more than the managerial class pursuing its own class interests under cover of altruism.

That, and not the state’s gentle native loopiness, is what is really behind “Six Californias,” the eccentric enthusiasm for subdividing California into six states: Having made a mess of the impoverished interior of the state, progressives seek to exile the poor and the unwashed to the new states of Central California (which gets Bakersfield and Stockton) and Jefferson (Chico, Redding), while Silicon Valley and the coastal stretch from Los Angeles up to San Luis Obispo get their own states — golden gated communities, in effect. Affluent progressives already have a great deal of social insulation — the Manhattan doorman serves the same purpose as the $5,000 rental in San Francisco — to keep them from interacting with the human effects of their policies. Journalists, senior bureaucrats, lawyers, union bosses — they all claim to know what’s best for the poor and the middle class, but they end up doing what’s best for themselves. And when the poor and the unglamorous grow sufficiently numerous and concentrated, then it’s time to build a Berlin wall between Malibu and Modesto.

Question: Which side of that wall do you think Bill Maher and Jon Stewart will live on? You think Rachel Maddow, the lawyer’s daughter, has been so much as downwind from a poor person not engaged as an intern at MSNBC? Don’t bet on it.

We see the same dynamic at play across our politics: Public-school teachers are insistent on maintaining their monopoly status, but in big cities such as Chicago they are unusually likely to send their own children to private schools. Similarly, Barack Obama thinks that school choice is great — for his daughters, but not for yours. They can make a mess of your schools, your neighborhoods, your community — they don’t live there.

That, too, is why conservatives favor government on the modest, manageable, local level. And that is why progressives want to centralize political power in Washington, and why they have more success in big cities such as Los Angeles and New York: If you were screwing the poor and the struggling while alleging to act on their behalf, would you be able to look them in the eye? Would you want to?

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Kevin D. Williamson is roving correspondent for National Review.