We used to make sure all Americans could lead a pretty good life

by Jon Margolis • Pittsburgh Post Gazette

One day last winter, Tom Ashbrook and his guests on his “On Point” public radio call-in program were talking about jobs and wages when a caller from Omaha named Valerie asked a blunt but valuable question.

One day last winter, Tom Ashbrook and his guests on his “On Point” public radio call-in program were talking about jobs and wages when a caller from Omaha named Valerie asked a blunt but valuable question.

Half the people, Valerie said, have an IQ of less than 100. “What do we do with all the ‘dumb’ people?” she wondered.

That sounds heartless, but Valerie didn’t seem to be scorning anyone as much as sympathizing with the increasingly bleak prospects some people are facing.

Valerie’s was not an original insight. Years earlier, the late columnist Murray Kempton noted that ours was a “society which, more lavishly than any in history, has managed the care and feeding of incompetent white people.”

Mr. Kempton, whose politics were left of center, was unhappy only because this management had not been extended to non-whites. He had no problem with the care and feeding function itself. He knew that many millions were not that brilliant or talented, and that society would have to be managed if they were to live decent lives.

And so it was. For decades, society passed laws, spent money, created programs and developed norms designed to make it more likely that those who lacked special talent or a college degree could feed and take care of themselves. They didn’t get rich. But wages, benefits and government subsidies combined to get most of them a medium-sized house, a not-too-old car or two and adequate food and clothing, with enough left over to have a little fun.

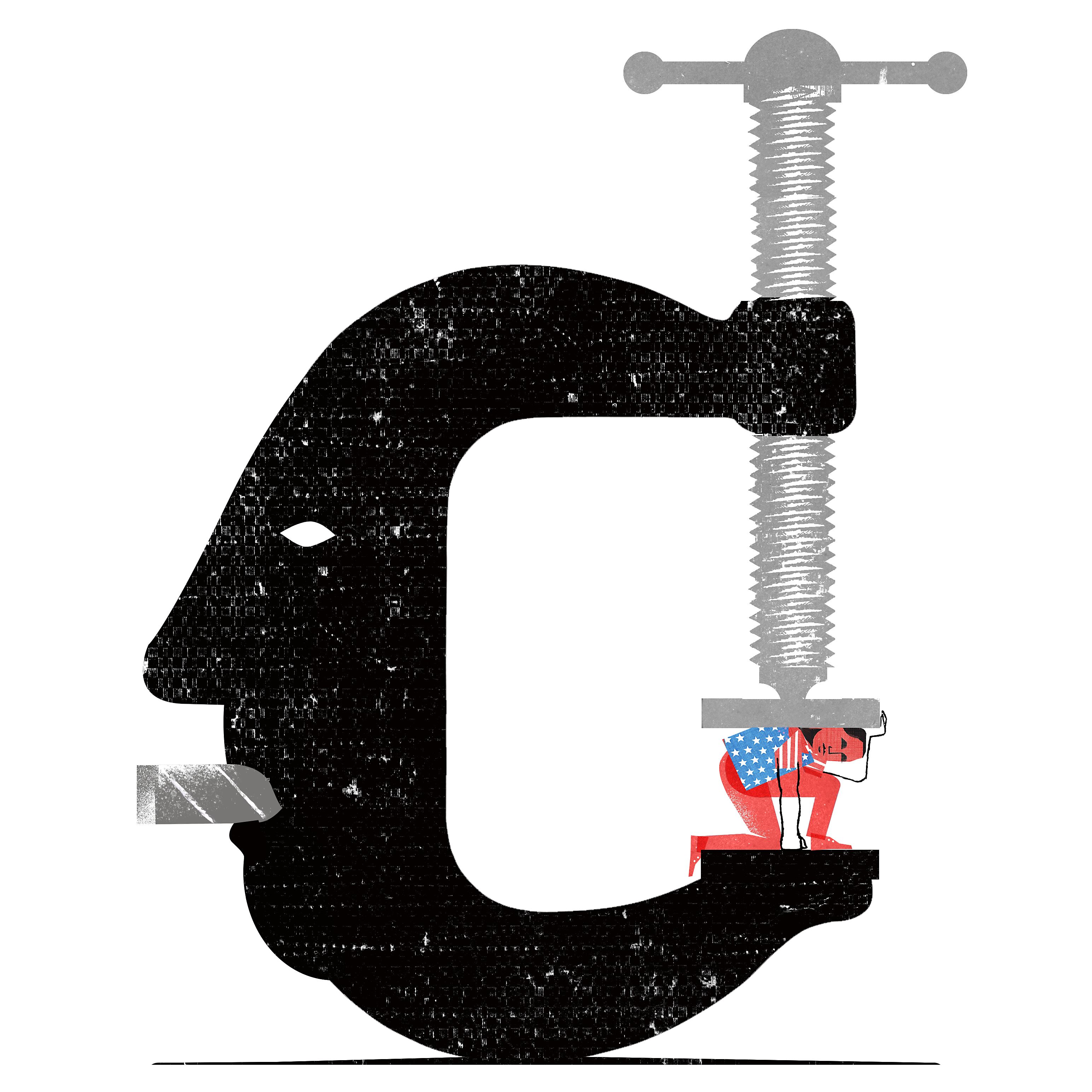

But for the last 30 years or so, society has done less to promote the well-being of the un-schooled and un-wealthy. That’s why so many who don’t go to college, don’t have a 95-mile-an-hour fastball and have modest ambitions aren’t living as well as their parents did. They aren’t dumber or less competent. They just don’t have the opportunities their parents did. It’s worthwhile to wonder why.

And to contemplate the possibility that part of the answer is that some powerful people don’t think they ought to have those opportunities.

The standard liberal reaction is to blame greed, to say that the wealthy just want more and use their political power to get it at the expense of everybody else. But this explanation may be unfair and — worse — inaccurate. Maybe there is a coherent philosophy here, a sincerely held belief with both an intellectual and a moral foundation.

Listen to conservative commentator Erick Erickson explain that he opposed raising the minimum wage because minimum wage earners are “people who failed at life” and therefore apparently are not worth more than $7.25 an hour.

Or take a look at former House Majority Leader Eric Cantor’s 2012 Labor Day message: “Today, we celebrate those who have taken a risk, worked hard, built a business and earned their own success,” as if those who merely stayed in the ranks of the employed didn’t matter.

Then there was Mitt Romney’s dismissal of 47 percent of the people “who will not take personal responsibility and care for their lives.”

Mr. Romney said that not long after choosing Rep. Paul Ryan of Wisconsin as his running mate. Before joining the Romney ticket, Mr. Ryan had been known primarily for his rigorous economic conservatism, influenced by his devotion to novelist/philosopher Ayn Rand.

Ms. Rand was prolific. As the prolific often are, she was verbose, so the quickest way to grasp her views about economic equity comes from the words of an admirer, the Austrian economist Ludwig Von Mises. She alone, he wrote, had “the courage to tell the masses what no politician told them: you are inferior …”

No free-marketer, Ms. Rand believed public policy should tilt in favor of the most productive and ambitious, those she called “geniuses.” The rest were “parasites.”

Or maybe “dumb” incompetents.

Here, perhaps, is the intellectual and moral foundation of a powerful if not quite dominant faction of today’s conservatism — the conviction that in this stratified society those in the highest economic strata are there because they deserve to be.

Meaning those in the middle and lower strata are down there because that’s where they deserve to be.

Not every economic conservative is an Ayn Rand disciple. But many are, even some who have never read her but have come under the sway of her prominent acolytes.

As speaker of the House, Mr. Ryan, who distanced himself from Ms. Rand’s atheism and “objectivist” philosophy but not her economic or political views, is more influential than ever. Former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan is a Rand disciple, as are conservative funders Charles and David Koch, and assorted columnists, academics and even actors. Together, these politicians and their supporters have devised policies that limit — if they do not actually suppress — the incomes of the non-wealthy.

Liberals complain that conservative policies hurt the poor. Perhaps they do. But liberals don’t seem to get that neo-Randites appear to be actually intent on opposing policies that improve the lives of those in the middle of the income spectrum, that is, “the masses.”

Consider what propelled Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker into the presidential race: eviscerating collective bargaining for state employees and supporting a “right-to-work” law.

Emasculating labor unions is only one way the neo-Randites are trying to manage society to provide less care and feeding of not-so-extraordinary people. They favor lower Social Security benefits, higher interest rates that reduce job growth, a high-valued dollar that makes U.S. manufacturing less competitive and free trade in goods produced by factory workers but not the services provided by doctors, lawyers and accountants.

One common outcome of these policies (and others) is to diminish the incomes of those whose incomes are already modest. If this is a common outcome, perhaps it is a common intent.

If so, it seems to be working. Ayn Rand and Ludwig von Mises would approve.

Jon Margolis is a former chief political correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, now retired and living in Vermont. He is the author of “The Last Innocent Year: America in 1964.”