Diffused democracy weakens centralized power. This is why Democrats hate it.

By David Harsanyi • The Federalist

This week, anti-Trump protesters hit the streets in big cities around the country, chanting “This is what democracy looks like!” Yes. That’s the problem.

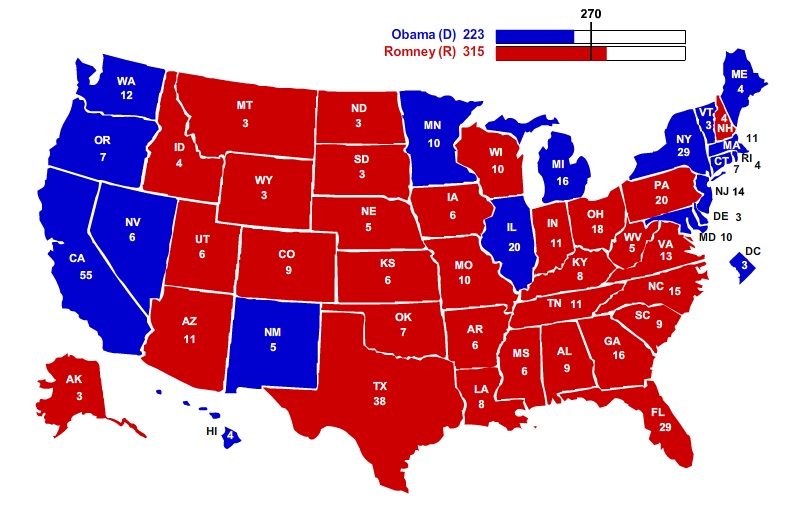

For many Democrats, the greatest political system is the one that instills their party with the most power. Now that it looks like Hillary Clinton will “win” the fictional popular vote over Donald Trump, people — not just young people who’ve spent their entire lives being told America is a democracy, but people who know better — are getting hysterical about the Electoral College. Not only is it “unfair” and “undemocratic,” but like anything else progressives dislike these days, it’s a tool of “White Supremacy—and Sexism.”

If liberals truly believe majoritarianism is the fairest way to run a government, then why shouldn’t 50 percent of states be able to repeal constitutional amendments? (Democrats only run only 13 state legislatures. But, you know, when it’s convenient.) Why should a bunch of white men from the late eighteenth century have any say in how contemporary Americans live? If proportional government is unfair, why do we even have two senators from each state? Why not 20 from California and one from Wyoming? Why have states at all? Maybe we should have a series of referendums instead of relying on Congress.

Maybe we should let protesters overturn elections?

This is simple: Trump cannot CANNOT be allowed a term in office. It’s not about 2018. It’s about RIGHT NOW

— Joss Whedon (@joss) November 14, 2016

Granted, because of our childish propensity to use the word “fair,” I understand that the Electoral College must seem like a relic that undercuts the sacramental notion of “one man, one vote.” As if a losing vote ever counts anyway. But if you still generally believe the Founders did a decent job setting up the conditions for material prosperity and individual freedom to guarantee a stable government and dispersed political power, you should be a big fan of the Electoral College.

If it needs repeating, in the United STATES of America, we have an Electoral College, wherein the president and vice president aren’t elected directly by the voters, but rather by electors who are chosen through the popular votes from each state. Your state’s portion of electors equals the number of members in its congressional delegation: one for each member in the House of Representatives plus two for your senators. We have 51 separate elections. This is done so that every part of the nation has some kind of say over the next executive. The president, after all, is not a monarch. He does not make laws. Not even Barack Obama was supposed to do that. Voters need to view the system as a whole to understand why this is “fair.”

Diffused democracy weakens the ability of politicians to scaremonger and use emotional appeals to take power. It blunts the vagaries of the electorate. So, naturally, the Left has been attacking the Electoral College for years — including talk of a national “compact” to circumvent smaller states. A few years ago, Alexander Keyssar, a professor of history and social policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School, penned an article in The New York Times about revising the Constitution:

If we were writing or revising the constitution now, we would almost certainly adopt a rather simple method of choosing our presidents: a national popular vote, followed by a run-off if no candidate wins a majority. We applaud when we witness such systems operating elsewhere in the world.

Perhaps we should try one here.

We do? We should? Why on earth would we do that? Which parliamentary setup is more stable than our form of governance? What free nation in the world has as consistently and peacefully been able to turn power from one political party to the next the way we have in the past 100 years?

That, of course, is the point. Need it be repeated, the Electoral College, and other mechanisms that balance democracy, create moderation and compromise—or, stop one party from accumulating too much power. It is certainly possible that Obama’s unilateral governance over the past eight years had a lot to do with the pushback of three consecutive losses in the Senate and Congress and the election of Donald Trump.

To some extent, the Electoral College impels presidents and their political parties to consider all Americans in rhetoric and action. By allowing Wyoming, with a population of less than 600,000, and California, with a population of more than 38 million people, both have two senators, we create more national cohesion. We protect large swaths of the nation from being bullied. We incentivize Washington—both the president and the Senate—to craft policy that meets the needs of Colorado as well as New York.

Moreover, besides protecting the rights of Americans who reside in those states, it should also remind us that smaller states have industries and functions that outweigh a measurement in population alone—the agriculture sector of a state, for instance. In a world with increasing productivity, this matters more than ever. Smaller states are laboratories for ideas, as are big ones. If they become marginalized, then coerced to embrace the policies favored by the people in urban areas, the nation loses valuable resourcefulness, imagination, and brainpower.

It’s also worth remembering that the dynamics of this election would be completely different if the popular vote actually mattered. The election is geared to winning states, not people. There is no guarantee that Hillary Clinton would have won. There are tons of conservatives in blue states, for instance, who do not vote because they understand that the majority around them have a different political outlook. A direct national election would mean focusing on blue-state Republicans and red-state liberals. I’m not sure that setup works out for Democrats exactly as they imagine.

It’s true that Americans don’t like the Electoral College. This, considering its purpose, is educationally irrelevant. Gallup has been gauging American sentiments on the Electoral College from different angles over the years. But no matter how pollsters phrase the question, impressive majorities always want to trash this unique buttress against direct democracy — and, since the question was first asked in 1966, it’s become increasingly unpopular.

My empirical experience tells me that public schools teach kids about American governance in a way that diminishes the importance of diffused democracy. They sure do spend precious little time on civics.

Now, some of this handwringing is a function of distraught voters trying to figure out ways to delegitimize Trump. Some of it is a function of “democracy” being misunderstood. How about tyranny of the minority, you ask? Good question. Let’s give power back to the states and stop treating the executive branch as if were a law-making branch of government. Washington was never intended to hold this much power over states. And presidents were never meant to be this important.