After a year of monitoring, the researchers found that the chemical-laced fluids used to free gas trapped deep below the surface stayed thousands of feet below the shallower areas that supply drinking water, geologist Richard Hammack said.

Although the results are preliminary — the study is still ongoing — they are a boost to a natural gas industry that has fought complaints from environmental groups and property owners who call fracking dangerous.

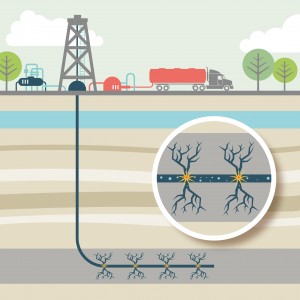

Drilling fluids tagged with unique markers were injected more than 8,000 feet below the surface, but were not detected in a monitoring zone 3,000 feet higher. That means the potentially dangerous substances stayed about a mile away from drinking water supplies.

“This is good news,” said Duke University scientist Rob Jackson, who was not involved with the study. He called it a “useful and important approach” to monitoring fracking, but cautioned that the single study doesn’t prove that fracking can’t pollute, since geology and industry practices vary widely in Pennsylvania and across the nation.

The boom in gas drilling has led to tens of thousands of new wells being drilled in recent years, many in the Marcellus Shale formation that lies under parts of Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio and West Virginia. That’s led to major economic benefits but also fears that the chemicals used in the drilling process could spread to water supplies.

The mix of chemicals varies by company and region, and while some are openly listed, the industry has complained that disclosing special formulas could violate trade secrets. Some of the chemicals are toxic and could cause health problems in significant doses, so the lack of full transparency has worried landowners and public health experts.

The study, done by the National Energy Technology Laboratory in Pittsburgh, marked the first time that a drilling company let government scientists inject special tracers into the fracking fluid and then continue regular monitoring to see whether it spread toward drinking water sources. The research is being done at a drilling site in Greene County, which is southwest of Pittsburgh and adjacent to West Virginia.

Eight new Marcellus Shale horizontal wells were monitored seismically and one was injected with four different man-made tracers at different stages of the fracking process, which involves setting off small explosions to break the rock apart. The scientists also monitored a separate series of older gas wells that are about 3,000 feet above the Marcellus to see if the fracking fluid reached up to them.

The industry and many state and federal regulators have long contended that fracking itself won’t contaminate surface drinking water because of the extreme depth of the gas wells. Most are more than a mile underground, while drinking water aquifers are usually within 500 to 1000 feet of the surface.

Kathryn Klaber, the CEO of the industry-led Marcellus Shale Coalition, called the study “great news.”

“It’s important that we continue to seek partnerships that can study these issues, and inform the public of the findings,” Klaber said.

While the lack of contamination is encouraging, Jackson said he wondered whether the unidentified drilling company might have consciously or unconsciously taken extra care with the research site, since it was being watched. He also noted that other aspects of the drilling process can cause pollution, such as poor well construction, surface spills of chemicals, and wastewater.

Jackson and his colleagues at Duke have done numerous studies over the last few years that looked at whether gas drilling is contaminating nearby drinking water, with mixed results. None of them have found chemical contamination, but they did find evidence that natural gas escaped from some wells near the surface and polluted drinking water in northeastern Pennsylvania.

Scott Anderson, a drilling expert with the Environment Defense Fund, said the results sound very interesting.

“Very few people think that fracking at significant depths routinely leads to water contamination. But the jury is still out on what the odds are that this might happen in special situations,” Anderson said.

One finding surprised the researchers: Seismic monitoring determined one hydraulic fracture traveled 1,800 feet out from the well bore; most traveled just a few hundred feet. That’s significant, because some environmental groups have questioned whether the fractures could go all the way to the surface.

The researchers believe that fracture may have hit naturally occurring faults, and that’s something both industry and regulators don’t want.

“We would like to be able to predict those areas” with natural faults and avoid them, Hammack said.

Jackson said the 1,800-foot fracture was very interesting, but also noted it is still a mile from the surface.

The DOE team will start to publish full results of the tests over the next few months, said Hammack, who called the large amount of field data from the study “the real deal.”

“People probably will be looking at the data for years to come,” he said.

. . . . . . . . . . .

This article was published by CBS News.