It was all hands on deck last month at the home of Washington, D.C., powerbroker Kiki McLean, according to the irrefragable Jonathan Swan of Axios. Some of the Democratic Party’s most experienced and influential female political operatives—Donna Brazile, Jen Palmieri, Stephanie Cutter, Minyon Moore—gathered for dinner to discuss a germinating crisis within their party. “These were old friends getting together for the first time since the pandemic began, and celebrating a Democratic president after the Trump years,” Swan reports. “But the dinner had an urgent purpose.” Its object was to salvage the career of Vice President Kamala Harris. I hope there was plenty on hand to drink.

The brain trust arrived at two conclusions. First, Harris should emphasize her years as California’s attorney general, thereby reducing her exposure to the charge that the Democrats are soft on crime. Second, the poohbahs decided that much of the criticism of Harris’s job performance amounts to sexism. “Many of us lived through the Clinton campaign, and want to help curb some of the gendered dynamics in press coverage that impacted HRC,” a source told Swan. The problem with ascribing your candidate’s difficulties to “gendered dynamics,” of course, is that it doesn’t work. A candidate is truly “impacted” by their own attributes and competence. Sexism didn’t bury Hillary Clinton’s campaign. Clinton did—with a big assist from Robby Mook.

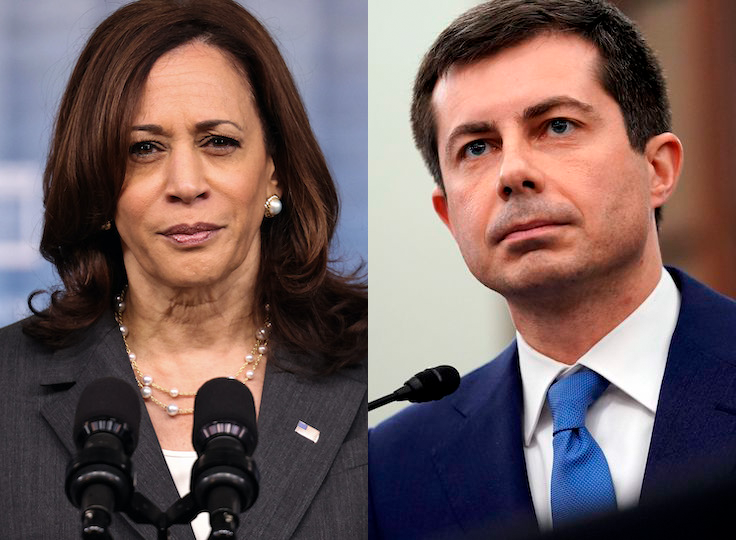

The subtext of Swan’s article, and much of the Harris commentary these days, is the 2024 election. President Biden is 78 years old. Professional Washington appears convinced that he will decide against running for a second term. Harris, as vice president, is Biden’s presumed successor. But the enthusiasm for her candidacy is not exactly overwhelming. Indeed, one of the most entertaining sideshows in the nation’s capital since January has been the steel cage match between Harris and her rival within the cabinet, Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg. The prize is the Democratic Party. At the moment, Mr. Secretary can say—in seven languages—that he’s winning.

Recent months have not been pleasant for Harris. Her policy portfolio, consisting of voting rights and the southern border, has seen diminishing returns. Neither the unconstitutional “For the People Act” nor the anachronistic “John Lewis Voting Rights Act” is headed for passage. The Justice Department lawsuit against Georgia’s recent election reform is likely to be tossed out of court. Meanwhile, illegal immigrants continue to cross the border in record numbers. Immigration is Biden’s worst issue—thanks, Kamala—and the ploy to address the “root causes” of migration in Central America is diversionary and futile.

Rep. Henry Cuellar (D., Texas) recently teamed up with Sen. Lindsey Graham (R., S.C.) and called on the president to install Jeh Johnson, former secretary of homeland security, as “border czar.” It is unlikely that Biden will follow their advice—the rebuke of Harris would be too obvious. But Cuellar’s desperation is impossible to ignore. “Democrats would do well to remember that public opinion polling over the years has consistently shown overwhelming majorities in favor of more spending and emphasis on border security,” writes demographer Ruy Teixeira in his invaluable newsletter the Liberal Patriot. And Democrats would do well to remember Vice President Harris’s approval rating: It’s upside down.

Buttigieg, by contrast, is cycling his way toward a bipartisan success. It’s true that transportation wasn’t his first pick: He wanted, by all accounts, to be U.N. ambassador. But there was no way Harris was going to let Biden park Buttigieg in the Ritz-Carlton in New York City, where he could spend four years burnishing his diplomatic credentials and wining and dining the financial services crowd that funds presidential campaigns. The U.N. job went to a career foreign serviceofficer instead.

As it happens, though, the transportation gig is working out for the former mayor of South Bend, Indiana. Buttigieg’s interviews are as gaffe-free (and as somnolent) as one might expect from someone who as a youth tested talking points in the mirror and dressed up as a “politician” for Halloween. The legislation with which he is most associated—the 2,700-page, $1 trillion Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework now under debate in the Senate—has a good chance of becoming law. And it’s popular.

Could Buttigieg leverage his experience managing a mid-level department into a winning presidential bid? Stranger things have happened, I suppose. What must keep Buttigieg up at night is his utter lack of appeal to the Democratic Party’s most important constituency: Recall the CNN poll from the summer of 2019 showing him with zero support among black voters. True, he tied Bernie Sanders in the Iowa caucus. But Iowa doesn’t make Democratic nominees—South Carolina does. And Buttigieg placed fourth in the Palmetto State.

Then again, Harris doesn’t have much of a track record with black voters, either. She dropped out of the Democratic primary before the voting began, so it’s hard to judge her against actual results. Which raises this conundrum: How can the Biden Democrats succeed—or even exist—without Joe Biden?

Harris and Buttigieg, the two most prominent options in 2024, are gentry liberals with tenuous connections to working-class Democrats and suburban independents. It’s fun to watch them one-up each other. But Democratic professionals, including Kiki McLean’s dinner companions, must be wondering who else is on offer. Or might it be the case that President Biden has set up his heirs for failure on purpose, so that his party three years from now has no choice but to renominate his 81-year-old self? Sure, Joe Biden is a little crazy. But maybe he’s crazy like a fox.