Paul J. Saunders

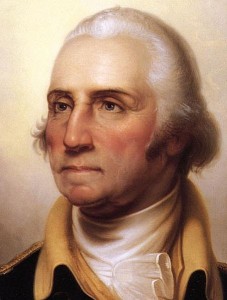

Eroding support for President Barack Obama’s domestic and foreign policies—reflected both in the editorial pages and in public opinion—has prompted many to suggest that the president should emulate Bill Clinton, Ronald Reagan and even his immediate predecessor George W. Bush, whom voters decisively rejected in 2008 to elect Mr. Obama. What the 44th president really needs is not to copy the 43rd or 42nd, however, but to look to the 1st: George Washington.

Washington’s America was obviously profoundly different from today’s in innumerable ways. It was a new country, weak both in the internal connections between states and in relation to Europe’s great powers. It covered only a small portion of modern-day America’s territory with a thin population, little industry, poor roads, and limited infrastructure. The federal government was still emerging. And the country was hardly what most Americans today would consider a democracy—only 6 percent of the population could vote, African slaves were counted at the rate of five slaves to three free citizens in apportioning seats in the House of Representatives, and even if Mr. Obama had been a free citizen (an unlikely prospect), he could never have won the office he now holds.

Nevertheless, George Washington and America’s other founders were nothing if not astute observers of politics and of the fundamental truths of human nature—only thus could they produce the remarkably successful United States Constitution, which has endured for well over two centuries with only minor adjustments. However much we may periodically pat ourselves on the back for the great strides the country has made, the political realities of that era still endure in most important respects. As Washington’s close friend and comrade-in-arms the Marquis de Lafayette might say, “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose”—the more things change, the more they stay the same.

No less important, before becoming president, Washington was a political general whose ultimate success may well have owed more to his ability to keep Americans united and focused on the war for independence than on his skill as a military strategist or tactician. It is easy to forget that individual state governments were often unwilling to contribute soldiers, money or supplies to fighting outside their own borders. Not to mention the divisions among Washington’s own commanders and the Continental Congress’s combination of interference in his decisions and unresponsiveness to his requests.

With all of this in mind, here are four lessons from George Washington’s Farewell Address—a contemplative and self-conscious message to the country and to future generations. Obama would do well to ponder them.

1. Cool the partisan combat—don’t fuel it. In the era before one-party government, Washington saw partisan differences—for example, those between Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton—come close to tearing his administration apart. Washington acknowledged that “the spirit of party” as he called it, “is inseparable from our nature, having its root in the strongest passions of the human mind.” Nevertheless, he said, in “popular” governments like America’s, “it is seen it its greatest rankness, and is truly their worst enemy.” The reason for this, he continued, is that “the alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissention, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism.” In brief: rule your partisan passions, or they will rule you. Mr. Obama will accomplish little in his remaining time in office if he does not take a different approach to governing.

There are, of course, two sides to every fight—and Congressional Republicans would do well to think about the ways in which partisanship damages America’s national interests and undermines public confidence in government, including if not especially the legislative branch. Nevertheless, the president is the president and has a special responsibility to lead by example—to prevent partisanship that Washington acknowledged in modest forms can serve as “useful checks upon the administration of the government” from “bursting into flame, lest, instead of warming, it should consume.”

2. Don’t try to circumvent the Congress. It is understandable that a president increasingly boxed-in by a hostile House of Representatives, and possibly soon by a hostile Senate too, should look for creative approaches to governing. Unfortunately, as Washington well recognized, over time this cannot but undermine the separation of powers that is the foundation of our limited government. It hard to imagine George Washington endorsing the current incumbent’s efforts to impose climate change policy through regulation, to implement immigration policy by publicly refusing to enforce the law, and to take myriad other steps that some liberal activists encourage to further their stalled agendas. As Washington put it, “the habits of thinking in a free country should inspire caution in those entrusted with its administration, to confine themselves within their respective constitutional spheres…. The spirit of encroachment tends to consolidate the powers of all the departments in one, and thus to create, whatever the form of government, a real despotism.” Washington well recognizes the temptation to circumvent constitutional procedures for noble ends and also condemns it: “…for though this, in one instance, may be the instrument of good, it is the customary weapon by which free government is destroyed.” (Those who want a modern example of this need look no further than Russia, where Boris Yeltsin’s determination to impose economic reform by decree despite parliamentary opposition laid the groundwork for Vladimir Putin’s rule.)

3. Think twice in dealing with allies… Washington’s advice to “steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world” is perhaps his most-quoted foreign policy statement. America today clearly benefits from its many allies and, more important, the first president explicitly clarified his attitude by saying “let me not be understood as capable of patronizing infidelity to existing arrangements”—his way of explaining that the United States has to live up to the alliance commitments it has made.

Nevertheless, Washington has some more sophisticated advice too. Perhaps most important, he notes that “a passionate attachment of one nation for another produces a variety of evils,” including “the illusion of an imaginary common interest in cases where no real common interest exists” that can lead to “participation in the quarrels and wars [of allies] without adequate inducement or justification.” It is striking today that America simultaneously has major allies in three strategically vital regions—Asia, Europe and the Middle East—that want us either to use force, to supply arms, or to take other steps that could lead (under the certain circumstances) to war. Precisely because these are strategic regions, and because our allies are our allies, the United States must do what is necessary to protect its interests and uphold its commitments. But the president should be much clearer in defining both.

4. …And in choosing enemies. Less well-known is Washington’s call to avoid “permanent, inveterate antipathies against particular nations.” As he puts it, “Antipathy in one nation against another disposes each more readily to offer insult and injury, to lay hold of slight causes of umbrage, and to be haughty and intractable, when accidental or trifling occasions of dispute occur. Hence frequent collisions, obstinate, envenomed, and bloody contests.” The development of this antipathy is often a two-way street, of course—just look at the U.S.-Russia relationship and (to a thankfully lesser degree) the U.S.-China relationship. (Perhaps most disturbing is the Japan-China relationship—see above.) But however they begin, Washington warns, these enduring antagonistic sentiments can lead to situations in which the government “adopts through passion what reason would reject.” And when “the peace often, sometimes perhaps the liberty, of nations, has been the victim.” President Obama could help to avoid the more dangerous outcomes by calibrating his rhetoric much more carefully—for example, by condemning conduct rather than leaders.

It is impossible to separate George Washington’s cautious approach to foreign policy from the realities of America’s post-revolutionary weakness—he saw enormous American potential that required a period of peace to be realized. Though he did not directly connect his domestic political advice to his foreign policy thinking in presenting his Farewell Address, his experience and sentiments are directly relevant to Barack Obama today because Obama, not unlike Washington, is attempting to avoid foreign entanglements to focus on what he calls “nation-building at home.”

Nevertheless, there is a stark difference between the two men: Washington urged and worked toward conciliation and compromise in order to make the best use of the breathing space he won by avoiding taking sides in the British-French rivalry. Though it was often frustrating to some of his supporters, he tried to remain above the political fray. In contrast, President Obama risks squandering the opportunity that he is buying through relative disengagement internationally by fanning partisan sentiments and pursuing controversial domestic policy goals that divide the electorate against itself. This risks producing the worst of both worlds—an America that is weaker both at home and abroad. George Washington understood quite well that building a nation requires building consensus; hopefully Mr. Obama will see this too, before it’s too late.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Paul J. Saunders is executive director of The Center for the National Interest and associate publisher of The National Interest.