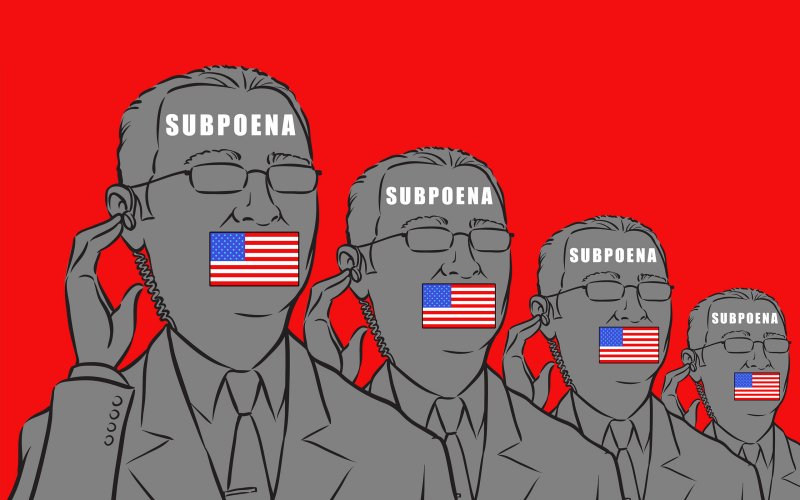

Reason.com, the website I edit, was recently commanded by the feds to provide information on a few commenters and not discuss it. Here’s why we’re speaking out.

by Nick Gillespie • The Daily Beast

Is there anything more likely to make you shit your pants out of a mix of fear and anger than getting a federal subpoena out of the blue?

Is there anything more likely to make you shit your pants out of a mix of fear and anger than getting a federal subpoena out of the blue?

Well, yes, there is: getting a gag order that prohibits you from speaking publicly about that subpoena and even the gag order itself. Talk about feeling isolated and cast adrift in the home of the free. You can’t even respond honestly when someone asks, “Are you under a court order not to speak?”

Far more important: talk about realizing that open expression and press freedom are far more tenuous than even the most cynical of us can imagine! Even when you have done nothing wrong and aren’t the target of an investigation, you can be commanded, at serious financial cost and disruption of your business, to dance to a tune called by the long arm of the law.

This all just happened to my colleagues and me at Reason.com, the libertarian website I edit. On May 31, I blogged about the life sentence given to Ross Ulbricht, the creator of the “dark web” site Silk Road, by Judge Katherine Forrest. In the comments section, a half-dozen commenters unloaded on Forrest, suggesting that, among other things, she should burn in hell, “be taken out back and shot,” and, in a well-worn Internet homage to the Coen Brothers movie Fargo, be fed “feet first” into a woodchipper.

The comments betrayed a naive belief in an afterlife and karma, were grammatically and spelling-challenged, hyperbolic, and… completely within the realm of acceptable Internet discourse, especially for an unmoderated comments section. (Like other websites, Reason is not legally responsible for what goes on in our comments section; we read the comments sometimes but don’t actively curate them.)

But the U.S. attorney for U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York thought differently and on June 2 issued a grand jury subpoena to Reason for all identifying information we had on the offending commenters—things such as IP addresses, names, emails, and other information. At first, the feds requested that we “voluntarily” refrain from disclosing the subpoena to anybody. Out of sense of fairness and principle, we notified the targeted commenters, who could have moved to quash the subpoena. Then came the gag order on June 4, barring us from talking about the whole business with anyone outside our organization besides our lawyers.

You can read a detailed account of how events, including the lifting of the gag order, played out here. As the legal blogger Ken White of Popehat has argued, the episode is plainly a huge abuse of power.

I’ll leave the detailed legal arguments to White, who confesses that once upon a time he was “an entitled, arrogant little douchesquirt when [he] was a federal prosecutor.” I’ve got my own reasons for seeing this episode as outrageous and something that all of us who read and write online—whether as bylined authors or anonymous commenters—should be worried about.

For starters, the subpoena was unnecessary because the comments obviously weren’t real threats. One of the commenters scooped up in this had written, “I hope there is a special place in hell reserved for that horrible woman” while another opined, “I’d prefer a hellish place on Earth be reserved for her as well.” What kind of country are we living in where you get in hot water for such tepid blaspheming? Even the more outrageous comments—“Its (sic) judges like these that should be taken out back and shot” —wouldn’t exactly stir fear in the heart of anyone who has accessed the Web since AOL stopped charging by the hour.

As White writes, “True threat analysis always examines context. Here, the context strongly weighs in favor of hyperbole. The comments are on the Internet, a wretched hive of scum, villainy, and gaseous smack talk. They are on a political blog, about a judicial-political story; such stories are widely known to draw such bluster. They are specifically at Reason.com, a site with excellent content but cursed with a group of commenters who think such trash talk is amusing.”

But here’s the thing we non-lawyers might think of first: To the extent that the feds actually thought these were serious plans to do real harm, why the hell would they respond with a slow-moving subpoena whose deadline was days away? By spending five minutes doing the laziest, George Jetson-style online “research” (read: Google and site searches), they would have found publicly available info on some of the commenters. I’m talking things like websites and Google+ pages. One of the commenters had literally posted thousands of comments at Reason.com, from which it is clear that he (assuming it is a he) is not exactly a threat to anyone other than common decency.

But that’s your tax dollars at work, costing a reputable, award-winning website—albeit one that is sharply critical of government when it comes to snooping in the boardroom and the bedroom—time and money to comply with a subpoena for non-threatening readers. Even worse, the feds are doing the same to readers who may or may not have any resources to help them comply with legal proceedings that can go very wrong very quickly.

“Subpoenaing Reason’s website records, wasting its staff’s time and forcing it to pay legal fees in hopes of imposing even larger legal costs (or even a plea bargain or two) on the average Joes who dared to voice their dissident views in angry tones sends an intimidating message: It’s dangerous not just to create something like Silk Road,” writes former Reason editor Virginia Postrel at Bloomberg View, concisely defining the chilling effect such actions have. “It’s dangerous to defend it, and even more dangerous to attack those who would punish its creator. You may think you have free speech, but we’ll find a way to make you pay.”

Getting a subpoena is like “only” getting arrested. It’s a massive disruption to anyone’s routine and should be reserved for moments when, you know, there’s actually something worthy of serious investigation. And chew on this: You’re only reading about this case because the subpoena became public after we disseminated it against the government’s wishes (and before it could get a gag order against us), and because we later got the gag order lifted. There’s every reason to believe that various publications, social media sites, and other platforms are getting tens of thousands of similar requests a year. How many of those requests are simply fulfilled without anyone knowing anything about them?

Disqus, the commenting service that many websites use to manage user feedback, claims “whenever legally permitted, and barring exceptional circumstances where safety or other factors are deemed a reasonable counteracting concern, Users should receive notice that their specific information is being requested with opportunity to inquire further or contest such requests.” So you’ll get notified, unless you don’t. Feel better now?

“Confidence in U.S. Institutions Still Below Historical Norms,” announces the headline for Gallup’s annual survey on how Americans feel about authorities and services ranging from banks to the military to business to various aspects of the government and law enforcement. Confidence in the police, the presidency, the Supreme Court, and Congress are all well below annual averages calculated since 1973 or 1993 (depending on the area). Broadly speaking, there’s no question that the country is becoming more libertarian—more skeptical of centralized power, especially when it’s wielded by the state. Until the next gag order, I’m happy to share with you one of the reasons why that might be happening.