On the subject of Egypt: Is it the U.S. government’s purpose merely to cop an attitude? Or does it also intend to have a policy?

An attitude “deplores the violence” and postpones a military exercise, as President Obama did from Martha’s Vineyard the other day. An attitude sternly informs the Egyptian military, as Sen. Lindsey Graham (R., S.C.) did, that it is “taking Egypt down a dark path, one that the United States cannot and should not travel with them.” An attitude calls for the suspension of U.S. aid to Egypt, as everyone from Rand Paul (R., Ky.) to Patrick Leahy (D., Vt.) has.

An attitude is a gorgeous thing. It is a vanity accountable to a conscience. But an attitude has no answer for what the U.S. does with or about Egypt once the finger has been wagged and the aid withdrawn. When Egypt decides to purchase Su-35s from Russia (financed by Saudi Arabia) and offers itself as another client to Vladimir Putin because the Obama administration has halted deliveries of F-16s, will Mr. Graham wag a second finger at Moscow?

Perhaps he will. Our diminished influence in Egypt may soon be reduced to nil, but at least our hands will be clean.

Or we could have a policy, which is never gorgeous. It is a set of pragmatic choices between unpalatable alternatives designed to achieve the most desirable realistic result. What is realistic and desirable?

Releasing deposed President Mohammed Morsi and other detained Brotherhood leaders may be realistic, but it is not desirable—unless you think Aleksandr Kerensky was smart to release the imprisoned Bolsheviks after their abortive July 1917 uprising.

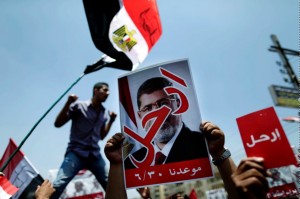

Restoring the dictatorship-in-the-making that was Mr. Morsi’s elected government is neither desirable nor realistic—at least if the millions of Egyptians who took to the streets in June and July to demand his ouster have anything to do with it.

Bringing the Brotherhood into some kind of inclusive coalition government in which it accepts a reduced political role in exchange for calling off its sit-ins and demonstrations may be desirable, but it is about as realistic as getting a mongoose and a cobra to work together for the good of the mice.

What’s realistic and desirable is for the military to succeed in its confrontation with the Brotherhood as quickly and convincingly as possible. Victory permits magnanimity. It gives ordinary Egyptians the opportunity to return to normal life. It deters potential political and military challenges. It allows the appointed civilian government to assume a prominent political role. It settles the diplomatic landscape. It lets the neighbors know what’s what.

And it beats the alternatives. Alternative No. 1: A continued slide into outright civil war resembling Algeria’s in the 1990s. Alternative No. 2: Victory by a vengeful Muslim Brotherhood, which will repay its political enemies richly for the injuries that were done to it. That goes not just for military supremo Abdel Fattah Al Sisi and his lieutenants, but for every editor, parliamentarian, religious leader, businessman or policeman who made himself known as an opponent of the Brotherhood.

Question for Messrs. Graham, Leahy and Paul: Just how would American, Egyptian, regional or humanitarian interests be advanced in either of those scenarios? The other day Sen. Paul stopped by the Journal’s offices in New York and stressed his opposition to any U.S. policy in Syria that runs contrary to the interests of that country’s Christians. What does he suppose would happen to Egypt’s Copts, who have been in open sympathy with Gen. Sisi, if the Brotherhood wins?

Of course there’s the argument that brute repression by the military energizes the Brotherhood. Maybe. Also possible is that a policy of restraint emboldens the Brotherhood. The military judged the second possibility more likely. That might be mistaken, but at least it’s based on a keener understanding of the way Egyptians think than the usual Western clichés about violence always begetting violence.

There’s also an argument that since our $1.3 billion in military aid hasn’t gotten Gen. Sisi to take our advice, we may as well withdraw it. But why should we expect him to take bad advice? Politics in Egypt today is a zero-sum game: Either the military wins, or the Brotherhood does. If the U.S. wants influence, it needs to hold its nose and take a side.

As it is, the people who now are most convinced that Mr. Obama is a secret Muslim aren’t tea party mama grizzlies. They’re Egyptian secularists. To persuade them otherwise, the president might consider taking steps to help a government the secularists rightly consider an instrument of their salvation. Gen. Sisi may not need shiny new F-16s, but riot gear, tear gas, rubber bullets and Taser guns could help, especially to prevent the kind of bloodbaths the world witnessed last week.

It would be nice to live in a world in which we could conduct a foreign policy that aims at the realization of our dreams—peace in the Holy Land, a world without nuclear weapons, liberal democracy in the Arab world. A better foreign policy would be conducted to keep our nightmares at bay: stopping Iran’s nuclear bid, preventing Syria’s chemical weapons from falling into terrorist hands, and keeping the Brotherhood out of power in Egypt. But that would require an administration that knew the difference between an attitude and a policy.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Bret Stephens is the deputy editorial page editor responsible for the international opinion pages of The Wall Street Journal.