Enormous pressure is being mounted to use our current crisis as an excuse to transform how we vote in elections.

“Coronavirus gives us an opportunity to revamp our electoral system,” Obama’s former attorney general, Eric Holder, recently told Time magazine. “These are changes that we should make permanent because it will enhance our democracy.”

The ideas Holder and others are proposing include requiring that a mail-in ballot be automatically sent to every voter, which would allow people to both register and vote on Election Day. It would also permit “ballot harvesting,” whereby political operatives go door-to-door collecting ballots that they then deliver to election officials. All of these would dramatically reduce safeguards protecting election integrity.

But liberals see a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to sweep away the current system. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi insisted that a mandatory national vote-by-mail option be forced on states in the first Coronavirus aid bill. She retreated only when she was ridiculed for shamelessly using the bill to push a political agenda. But Pelosi has promised her Democratic caucus that she will press again to overhaul election laws in the next aid bill.

If liberals can’t mandate vote-by-mail nationally, they will demand that states take the lead. Last Friday, California’s governor, Gavin Newsom, signed an executive order requiring that every registered voter — including those listed as “inactive” — be mailed a ballot this November.

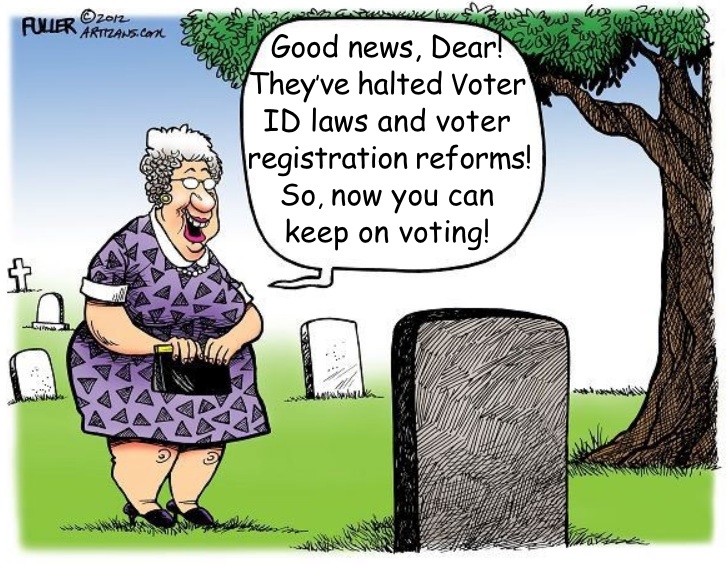

This could be a disaster waiting to happen. Los Angeles County (population 10 million) has a registration rate of 112 percent of its adult citizen population. More than one out of every five L.A. County registrations probably belongs to a voter who has moved, or who is deceased or otherwise ineligible.

Just last January, the public-interest law firm Judicial Watch reached a settlement agreement with the State of California and L.A. County officials to begin removing as many as 1.5 million inactive voters whose registrations may be invalid. Neither state nor county officials in California have been removing inactive voters from the rolls for 20 years, even though the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed last year, in Husted v. Randolph Institute, a case about Ohio’s voter-registration laws, that federal law “makes this removal mandatory.”

Experts have long cautioned against wholesale use of mail ballots, which are cast outside the scrutiny of election officials. “Absentee ballots remain the largest source of potential voter fraud,” was the conclusion of the bipartisan 2005 Commission on Federal Election Reform, chaired by former president Jimmy Carter and former secretary of state James Baker.

That remains true today. In 2012, a Miami–Dade County Grand Jury issued a public report recommending that Florida change its law to prohibit “ballot harvesting” unless the ballots are “those of the voter and members of the voter’s immediate family.” “Once that ballot is out of the hands of the elector, we have no idea what happens to it,” they pointed out. “The possibilities are numerous and scary.”

Indeed. In 2018, a political consultant named Leslie McCrae Dowless and seven others were indicted on charges of “scheming to illegally collect, fill in, forge and submit mail-in ballots” to benefit Republican congressional candidate Mark Harris, the Washington Post reported. The fraud was extensive enough that Harris’s 900-vote victory was invalidated by the courts and the race was rerun.

Texas has a long history of intimidation and coercion involving absentee ballots. The abuse of elderly voters is so pervasive that Omar Escobar, the Democratic district attorney of Starr County, Texas, says, “The time has come to consider an alternative to mail-in voting.” Escobar says it needs to be replaced with “something that can’t be hijacked.”

Even assuming that the coronavirus remains a serious health issue in November, there is no reason to abandon in-person voting. A new Heritage Foundation report by Hans von Spakovsky and Christian Adams notes that in 2014, the African nation of Liberia successfully held an election in the middle of the Ebola epidemic. International observers worked with local officials to identify 40 points in the election process that constituted an Ebola transmission risk. Turnout was high, and the United Nations congratulated Liberia on organizing a successful election “under challenging circumstances, particularly in the midst of difficulties posed by the Ebola crisis.”

In Wisconsin recently, officials held that state’s April primary election in the middle of the COVID-19 crisis. Voters who did not want to vote in-person, including the elderly, could vote by absentee ballot. But hundreds of thousands of people cast ballots at in-person locations, and overall turnout was high. Officials speculated that a few virus cases “may” have been related to Election Day, but, as AP reported, they couldn’t confirm that the patients “definitely got [COVID-19] at the polls.”

In California, the previous loosening of absentee ballot laws have sent disturbing signals. In 2016, a San Pedro couple found more than 80 unused ballots on top of their apartment-building mailbox. All had different names but were addressed to an 89-year-old neighbor who lives alone in their building. The couple suspected that someone was planning to pick up the ballots, but the couple had intercepted them first. In the same election, a Gardena woman told the Torrance Daily Breeze that her husband, an illegal alien, had gotten a mail-in ballot even though he had never registered.

“I think it’s a huge deal,” she said. “Something is definitely wrong with the system.”

The Los Angeles Times agrees. In a 2018 editorial it blasted the state’s “overly-permissive ballot collection law” as being “written without sufficient safeguards.” The Times concluded that “the law passed in 2106 does open the door to coercion and fraud and should be fixed or repealed.” It hasn’t been.

John Lieberman, a Democrat living in East Los Angeles, wrote in the Los Angeles Daily News that he was troubled by how much pressure a door-to-door canvasser put on him to fill out a ballot for candidate Wendy Carrillo. “What I experienced from her campaign sends chills down my spine,” he said.

What should also spook voters who want an honest election is a report from the U.S. Election Assistance Commission. It found that, in 2016, more mail ballots were misdirected to wrong addresses or unaccounted for than the number of votes separating Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. She led by 2.9 million votes, yet 6.5 million ballots were misdirected or unaccounted for by the states.147

It would be the height of folly for other states to follow California’s lead. In the Golden State, it already takes over a month to resolve close elections as mail-in ballots trickle in days and weeks after Election Day. Putting what may be a supremely close presidential election into the hands of a U.S. Postal Service known for making mistakes sounds like a recipe for endless litigation and greatly increased distrust in our democracy.