Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen got into trouble Tuesday for telling the truth. That morning, at a conference sponsored by the Atlantic, she raised the possibility that one day the Federal Reserve may raise interest rates “to make sure our economy doesn’t overheat.”

Anyone with a basic understanding of economics knew what she was talking about. The combination of President Joe Biden’s gargantuan spending and the accelerating economic recovery may well lead to a rise in consumer prices and hikes in interest rates. But an end to the Federal Reserve’s program of easy money would hurt asset prices and possibly employment as well.

Which is not what most investors want to hear. When Yellen’s words reached Wall Street, the market tanked. By the afternoon she was in retreat, telling the Wall Street Journal CEO summit that she had been misunderstood. “So let me be clear,” she said. “That’s not something I’m predicting or recommending.”

No, of course not. But it still might happen anyway.

A specter is haunting the Biden administration—the specter of inflation. Past inflations have not only harmed consumers, savers, and people on fixed incomes. They have also brought down politicians. Among the risks to the Democratic congressional majority is a rise in prices that lifts inflation to near the top of voters’ concerns, coupled by the type of Fed rate increase that hits stocks and housing. Inflation is one more signpost on the road to Republican revival, along with illegal immigration, crime, and semi-closed public schools embracing far-left critical race theory.

The classic definition of inflation is too much money chasing too few goods. That might also describe America sometime soon—if not already. The economy has started its post-virus comeback. Jobs and growth are on the upswing. U.S. households sit on a trillion-dollar pile of savings. Over the last year, on top of its regular spending, the federal government has appropriated a mind-boggling amount of money: a $2 trillion CARES Act, a $900 billion COVID-19 relief bill, and a $2 trillion American Rescue Plan. And President Biden wants to spend about $4 trillion more.

Surging this incredible amount of cash into an economy that is rapidly approaching capacity may have unintended and harmful consequences. But the Biden administration is either unconcerned about inflation or afraid of bringing it up in public.

Why? Well, one reason is that earlier warnings, after the global financial crisis in particular, didn’t seem to come true. (The inflation may have shown up in the dramatic ascent in prices of stocks and bonds, as well as in odd places such as the market for high-end art.) Another reason is that some economists think a little bit of inflation would be a good thing. But the main explanation may be related to status-quo bias: Inflation hasn’t been a driving force in our economic and public life for decades, and so we blithely assume it won’t be in the future.

Which is why an experienced leader worries about repeating the mistakes of the past. And yet, for a politician who came to Washington in 1973, Joe Biden has a lackadaisical attitude toward inflationary fiscal and monetary policy. Was he paying attention? It was the great inflation of the ’60s and ’70s, caused in part by high spending, the Arab oil embargo, and spiraling wages and prices in a heavily regulated and unionized economy, that helped ruin the presidencies of Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter.

Inflation led to bracket creep, with voters propelled into higher income tax brackets by monetary forces over which they had no control. And bracket creep inspired the tax revolt, supply-side economics, and the Reaganite idea that, “In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” The eventual cure for inflation was the painful “shock therapy” administered by Federal Reserve chairman Paul Volcker and what at the time was the worst recession since the Great Depression.

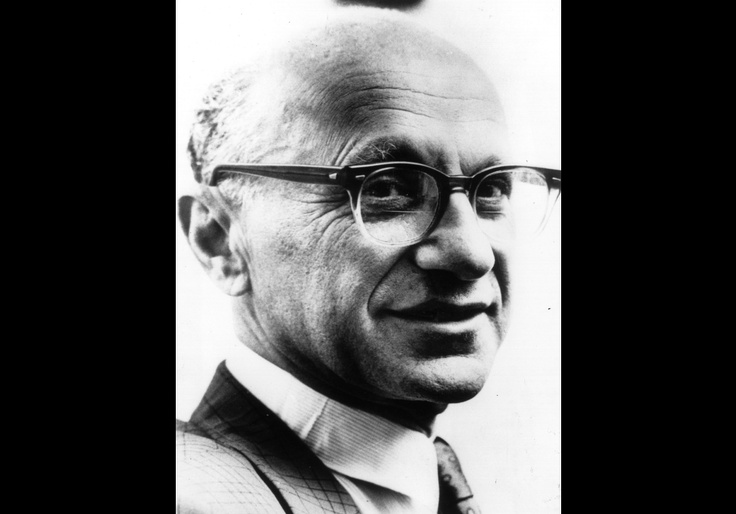

Why anyone would want to repeat this experiment in the dismal science is a mystery. Biden, however, is fixated not on inflation but on repudiating the legacy of the man known for describing it as “always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

Milton Friedman, whose empiricism led him to embrace free market public policy, was the most influential economist of the second half of the 20th century. But Biden has a weird habit of treating Friedman as a devilish spirit who must be exorcised from the nation’s capital. For Biden, Friedman represents deregulation, low taxes, and the idea that a corporation’s primary responsibility is not to a group of politicized “stakeholders” but to its shareholders. “Milton Friedman isn’t running the show anymore,” Biden told Politico last year. “When did Milton Friedman die and become king?” Biden asked in 2019. The truth is that Friedman, who died in 2006, has held little sway over either Democrats or Republicans for almost two decades. But Biden wants to mark the definitive end of Friedman and the “neoliberal” economics he espoused by unleashing a tsunami of dollars into the global economy and inundating Americans with new entitlements.

The irony is that Biden’s rejection of Friedman’s teachings on money, taxes, and spending may bring about the same circumstances that established Friedman’s preeminence. In a year or two, the American economy and Biden’s political fortunes may look considerably different than when Janet Yellen blurted out the obvious about inflation. Voters won’t like the combination of rising prices and declining assets. Biden’s experts might rediscover that it is difficult to control or stop inflation once it begins. And Milton Friedman will have his revenge.