By David French • National Review Online

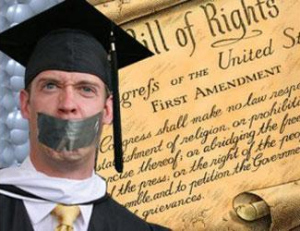

If you follow free-speech controversies for any length of time, you’ll understand two things about public opinion. First, an overwhelming percentage of Americans will declare their support for free speech. Second, a shocking percentage of Americans also support censoring speech they don’t like. How is this possible? It’s simple. “Free speech” is good speech, you see. That’s the speech that corrects injustices and speaks truth to power. That other speech? The speech that hurts my feelings or hurts my friends’ feelings? That’s “hate speech.” It might even be violence.

A new survey of college students demonstrates this reality perfectly. Conducted by McLaughlin & Associates for Yale’s William F. Buckley, Jr. Program, the survey queried 800 college students attending four-year private or public colleges, and the results were depressingly predictable.

First, the “good” news. Students claim to love free speech and intellectual diversity. For example, 83 percent agree that the First Amendment needs to be “followed and respected.” A whopping 84 percent agree that their school should “always do its best to promote intellectual diversity,” including by protecting free speech and inviting controversial speakers to campus. Similarly, 93 percent agree that there’s value in listening to and understanding “views and opinions that I may disagree with.”

But that’s not good news at all. It’s simply evidence that in the abstract students will claim to be open-minded. They’ll claim to value different views — right until the moment they really get offended. For example, 81 percent agree with the statement that “words can be a form of violence.” A full 58 percent of students believe that colleges should “forbid” speakers who have a “history of engaging in hate speech.”

And what is hate speech? The definition the students liked was staggeringly broad. Two-thirds agreed that hate speech is “anything that one particular person believes is harmful, racist, or bigoted.” They further agreed that hate speech “means something different to everyone.”

Given these realities, it should come as no surprise that large numbers of students believe that interruptions or even violence are appropriate to stop offensive speech. Almost 40 percent believe that it’s “sometimes appropriate” to “shout down or disrupt” a speaker. A sobering 30 percent believe that physical violence can be used to stop someone from “using hate speech or engaging in racially charged comments.”

It’s a small consolation that a slight majority of students say that they have not felt intimidated out of expressing their views — but this means that, in institutions allegedly dedicated to critical thinking and open inquiry, almost half the student respondents indicated they were indeed intimidated.

Survey findings like this should serve as an alarm bell every bit as important as the shout-downs and attacks that dominate the headlines. Naysayers and defenders of the status quo on campus will argue that the censors represent a mere fringe, that our campuses are still more free than critics suggest. That may be true on some campuses, but these poll numbers indicate that the so-called radicals are perhaps more mainstream than we’d like to admit.

Just at the moment when we need a concerted, bipartisan effort to defend a culture of free speech, our national polarization stands in the way. It becomes more important to win news cycles or to defeat a hated opponent than it is to defend an enduring civilizational value. We care only when our friends suffer censorship, and we sometimes even take a measure of glee when our opponents twist in the wind. Last week leftist protesters blocked an ACLU representative from speaking at William & Mary. Conservatives should find that every bit as outrageous as an effort to censor my friend Ben Shapiro. We should treat the president’s calls to punish kneeling football players with the exact contempt that we’d treat progressive calls for reprisals against a praying athlete.

In other words, it’s time to remember that we can strongly disagree with expression — as I disagree with the decision to kneel — while still protecting the right to dissent. Even more, it’s time to remember that the impulse to censor is often more offensive than the content of the targeted speech. After all, a kneeling football player doesn’t threaten our constitutional order. Campus speeches don’t threaten our individual liberty. But when presidents forget their constitutional role — or when campus administrators capitulate to the demands of the angry mob — we incrementally lose respect for the values that truly make America great.

Long after even the memories of modern feuds fade, the First Amendment should still stand. We should still fight for the rights of others that we’d like to exercise ourselves. But if we lose the culture, we’ll eventually lose the Constitution, and when that happens America will fundamentally and perhaps irrevocably change. When it comes to the fight for free speech, the stakes are exactly that high.

— David French is a senior writer for National Review, a senior fellow at the National Review Institute, and an attorney.