Despite its string of spectacular atrocities, Boko Haram is but a superficial byproduct of the deeply flawed Nigerian state. Nigeria is ridden with fatal fissures that ultimately may splinter Africa’s most populous and richest country.

Like mid-19th century America, Nigeria hosts two civilizations: one secular-modern, the other religious-traditional. Moreover, this dichotomy is defined by two separate systems of law. After Nigeria jettisoned its British colonial influenced parliamentary system in 1979, it adopted a U.S.-style constitution. It established a presidency and a federalist state structure, crafted to encourage the development of a liberal-democratic secular society and capitalist economy. Unfortunately for Nigeria, in 1999, the central government in Lagos bowed to clerical pressure and alleged popular demand, authorizing the implementation of Islamic Sharia as the primary legal code for its Muslim majority states.

In its five decades of independence, Nigeria has survived a brutal civil war, several military coups, endemic political corruption, and a topographically-defined ethnic divide. The Hausa people live in the semi-desert north and the Yoruba and Ibo peoples in the Savanna-grassland south. However, the different religious worldviews between Nigeria’s Islamic north and Christian south may yet lead to the country’s dissolution into two or more states. This co-existent incongruence has, in recent years, frayed normative civility among politicians, merchants, clerics, and Nigeria’s citizenry.

The largely Hausa Muslim north has become economically and politically isolated from the rest of the country. The region’s Islamic clerics are more dogmatic in doctrine and less tolerant of difference. The Ulama (Muslim teachers) have adopted an aggressive, proselytizing edge, especially in the country’s religiously-mixed middle corridor of states. In turn, the Christian south has responded with a defensive mobilization of its political resources. In addition, the Christians have become better organized to resist Muslim zealotry. Moreover, more activist Christian sects, e.g., Pentecostals and Evangelicals, have recently experienced greater success at winning converts. Their own zealotry has unnerved Nigeria’s Muslim clergy.

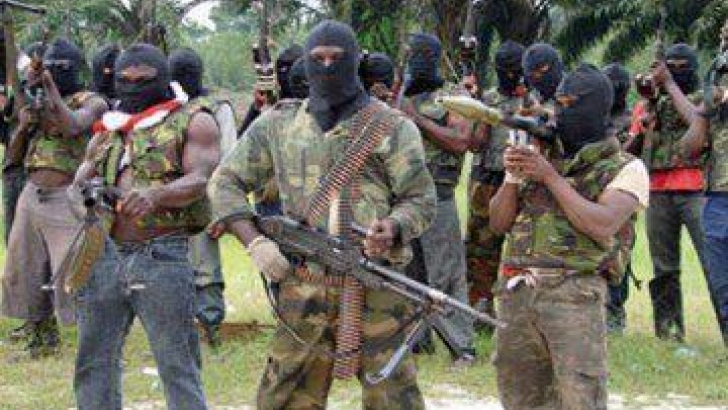

The confessional competition between Muslim and Christian is violently played out in the impoverished and terrorist-infested northeast and in the nation’s middle belt. Boko Haram is most interested in purging the north of any central government institutions as well as uprooting traditional Muslim lines of authority. In the mid-country states, extremist Muslims are attempting to cleanse this region of Christian communities.

This “spiritual” drive south also has environmental and occupational dimensions. Until recently, the Muslim march south in Africa was halted by topography and disease. Just south of the equator, an approximately 200 mile-wide expanse of desert gradually gives way to savanna, making it difficult for camel and horse to advance. Moreover, these beasts of burden, along with their human hosts, were devastated by tsetse-fly initiated sleeping sickness and mosquito-borne malaria. Yet, as a consequence of automotive transport and modern medicine, Islam’s southward impetus has been re-invigorated. You can tell by an uptick in the body count.

However, not all of the strife within Nigeria can be attributed to religious zealotry. The middle corridor of Nigeria’s states also features a livelihood boundary between northern cattle herders and southern farmers. This divide is not unlike the profile that fueled, in part, the strife in Darfur, Sudan. The violence in Nigeria’s Plateau State largely can be attributed to this clash of occupational pursuits.

Finally, debilitating problems endemic to Nigeria still persist: institutional corruption, bureaucratic inefficiency, and unequal regional distribution of oil revenues. Foreign tourists and businessmen quickly discover that the bribe is a necessary fact of life in Nigeria, whether it is to ward off police harassment, guarantee a seat in a flight out of the country, or to secure an appointment with a government official. Moreover, despite its natural wealth, Nigeria remains one of the poorest per capita countries in the world, a testament to its systemic corruption and inefficiency. The country is infamous for its international business scams as well as for being the principal transshipment site for illegal drugs in West Africa. This combination of confessional intolerance and ingrained incompetence paints a dark future for Nigeria. Unless the federal constitution becomes in actuality the supreme law of the land, submerging Sharia legal state structures (Sharia Law exists in 12 of Nigeria’s 36 states), the center will not hold. Nigeria, as we know it today, will not endure.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Dr. Lawrence A. Franklin is a Colonel in the U.S. Air Force Reserves.