Why the House continues to investigate.

NBC News’s Chuck Todd, speaking on MSNBC Tuesday morning, contended that the newly formed House select committee investigating Benghazi was likely to rehash familiar arguments and miss broader issues worth discussing:

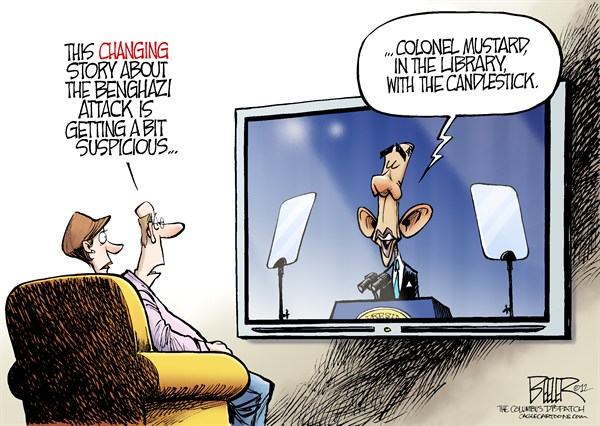

It certainly looks more partisan than it looks like a serious inquiry. They’ve done a ton of these inquiries already, the House has. There’s been a Senate Intelligence investigation. Forget just the State Department. I think you could argue that yes, Congress should have done what it did, which is go through some of these committees. But as for the need for the select committee — you know, I’ll hear from Republicans that say, ‘But there are unanswered questions!’ Well, no, all the questions have been answered. There’s just some people that don’t like the answers, that wish the answers were somehow more conspiratorial, I guess.

Their focus seems to be off. Have a conversation about the policy. Have a debate, an investigation into whether the policy is working; to whether the response to the Arab Spring, whether we did the right thing with the light footprint in Libya. But to sit here and investigate talking points seems to be totally missing the larger point here. It’s like investigating who cut down one tree in a forest that’s been burned down.”

Todd is half-right that there are broader issues worth examining. But there is good reason for Republicans to believe that full answers have been withheld, and Americans have seen little or no real accountability for a largely preventable outrage.

As Todd notes, several House and Senate committees launched their own inquiries, but the White House withheld certain documents and evidence, which raises serious doubts about how thoroughly and accurately those committees’ questions have been answered. For example, the White House never sent Congress an e-mail from Ben Rhodes instructing then–ambassador to the United Nations Susan Rice to “underscore these protests are rooted in an Internet video, and not a broader failure of policy,” infuriating lawmakers.

White House press secretary Jay Carney told reporters the White House didn’t include the e-mail in its disclosures to Capitol Hill because it wasn’t about Benghazi, but ABC News’s Jonathan Karl noted that the e-mail in question has an entire section labeled “Benghazi.” How many other documents have been withheld because the administration judged them not relevant, were momentarily struck with inexplicable illiteracy, or simply deemed them too damaging or embarrassing to turn over to Congress?

Earlier, senators had complained about heavily redacted documents:

“It was so redacted that there was no information whatsoever,” said the source, who spoke to Fox on the condition they not be identified. “There were some documents that were 100 pages with every word on the page redacted. They were worthless.”

More than a year after the attack, Senator Lindsey Graham (R., S.C.) was informed that he could not interview the survivors of the attack because it would somehow interfere with the criminal prosecution of the perpetrators. This decision came as surprising news to FBI director James Comey, whose agency is responsible for that prosecution. Comey said he had no objection to the interviews. After Graham finally did speak with the survivors, he said some told him “they’ve been told to be quiet.”

While it’s entirely possible that Graham is misinterpreting or mischaracterizing the survivors’ comments, it’s impossible to know as long as the survivors’ comments and testimony remain hidden from the public. When the public has gotten to hear from those close to the events on the ground, such as Gregory Hicks, the former deputy chief of mission in Libya who was in Tripoli at the time of the attack, the testimony has offered a gripping, eye-opening, and disturbing portrait of the U.S. government being caught flat-footed and unable to mobilize in a crisis.

This is a particularly cynical strategy by the administration: They take as long as possible to provide the information and then complain that Congress remains obsessed with long-ago issues. Former National Security Council spokesman Tommy Vietor exemplified the delay-then-demand-others-move-on approach when he recently told Fox News Channel’s Bret Baier, “Dude, this was like two years ago.”

Finally, Carney recently suggested the White House may not cooperate with this new House panel because the Obama administration had not yet decided whether it deemed it a “legitimate” investigation.

Withheld documents, implausible explanations, inexcusable delays, allegations of witness and whistleblower intimidation, and threats to ignore the inquiries entirely mean the White House cannot be given the benefit of the doubt.

Representative Trey Gowdy, the chairman of the special panel, says Congress is getting some documents 20 months after requesting them, and for what it is worth, says he has evidence “there was a systematic, intentional decision to withhold certain documents from Congress.” However, he has not yet produced that unspecified evidence.

When Chuck Todd says all the questions have been answered, he probably is referring to reports like this one from the House Armed Services Committee, which concluded, among other things, “There was no ‘stand down’ order issued to U.S. military personnel in Tripoli who sought to join the fight in Benghazi.”

But that report was nowhere nearly as exculpatory as that one sentence suggests. In fact, the House report they’re citing was in fact pretty damning:

In assessing military posture in anticipation of the September 11 anniversary, White House officials failed to comprehend or ignored the dramatically deteriorating security situation in Libya and the growing threat to U.S. interests in the region. Official public statements seem to have exaggerated the extent and rigor of the security assessment conducted at the time.

In layman’s terms, the administration lied; more specifically, former secretary of defense Leon Panetta, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Martin Dempsey, and General Ham, commander of U.S. Africa Command, contradicted each others’ testimony about how much the administration and military were evaluating threats in the days leading up to September 11. This is hardly an “answered question.”

The House Armed Services Committee also concluded:

U.S. personnel in Benghazi were woefully vulnerable in September 2012 because a.) the administration did not direct a change in military force posture, b.) there was no intelligence of a specific “imminent” threat in Libya, and c.) the Department of State, which has primary responsibility for diplomatic security, favored a reduction of Department of Defense security personnel in Libya before the attack.

The U.S. military’s response to the Benghazi attack was severely degraded because of the location and readiness posture of U.S. forces, and because of lack of clarity about how the terrorist action was unfolding. However, given the uncertainty about the prospective length and scope of the attack, military commanders did not take all possible steps to prepare for a more extended operation.

Even with no particular “stand down” order from the administration, a small team was ordered to stay in Tripoli, Libya, instead of joining the fight in Benghazi:

However, after the diplomatic staff had been moved to what Lieutenant Colonel Gibson considered a “secure” location in Tripoli, he informed AFRICOM that he was about to take his three special operators to Benghazi on a Libyan transport plane. At that time, Rear Admiral Brian L. Losey, SOCAFRICA’s commander, conveyed an order to Lieutenant Colonel Gibson to remain in Tripoli to defend Americans there. Rear Admiral Losey said he was concerned about the possibility of follow-on attacks in Tripoli or a potential for attempts at hostage taking. Preferring to move, however, Lieutenant Colonel Gibson told the committee he was “visibly upset” at the time. But Rear Admiral Losey explained to the committee that it was rooted in his belief that Lieutenant Colonel Gibson’s team was “the only military element . . . in Tripoli that had any security experience whatsoever” and “it seemed prudent” to divide the few military personnel in Libya between Tripoli and Benghazi rather than concentrate them in one location.

Some may look at that report and cite it as evidence that the questions have been answered, but the description of the readiness of U.S. forces raises more troubling questions: At any point during the evening did the commanding officers reevaluate the decision to keep those four special operators in Tripoli instead of letting them attempt a rescue in Benghazi? How did the U.S. mission in Libya reach the point where one of the most consequential choices of the night was the decision to keep four men guarding the embassy in Tripoli instead of attempting a rescue in Benghazi? Whose idea was it to have a special-operations unit assigned to the European Command, known as a Commander’s In-Extremis Force, on a training mission on the anniversary of the 9/11 attacks? How did the U.S. reach the point where neither the U.S. military nor a single NATO ally had any planes that were combat-ready and capable of assisting in a battle on the other side of the Mediterranean?

For all of the discussion about Susan Rice’s talking points, few have noticed that the State Department issued a statement the night of September 11 — six hours into a seven-hour assault — attributed to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton that suggests the attack was a response to “inflammatory material posted on the Internet.” (Notice this statement is specifically about Benghazi, not the violent protest outside the U.S. Embassy in Egypt earlier in the day.)

I condemn in the strongest terms the attack on our mission in Benghazi today. As we work to secure our personnel and facilities, we have confirmed that one of our State Department officers was killed. We are heartbroken by this terrible loss. Our thoughts and prayers are with his family and those who have suffered in this attack.

This evening, I called Libyan President Magariaf to coordinate additional support to protect Americans in Libya. President Magariaf expressed his condemnation and condolences and pledged his government’s full cooperation.

Some have sought to justify this vicious behavior as a response to inflammatory material posted on the Internet. The United States deplores any intentional effort to denigrate the religious beliefs of others. Our commitment to religious tolerance goes back to the very beginning of our nation. But let me be clear: There is never any justification for violent acts of this kind.

As many have noted, no one on the ground characterized the events as a protest or mentioned anything about the video. This release, strangely little-discussed considering the heated debate over Benghazi, strongly suggests that the State Department perceived the Benghazi attack as tied to the video before any evidence pointed to that direction. In fact, they came to this conclusion before the attack finished.

Many in the conservative grassroots echo Andrew Malcolm in asking what President Obama did that evening. This is one area where the questions have indeed been answered. Again, from the House Armed Services Committee report:

Secretary Panetta and General Dempsey then left for the White House to attend an unrelated routine weekly meeting with the President. Upon arrival, the two discussed the attack with the President for fifteen to thirty minutes, at which time they presumably shared all that was known about the unfolding events, including the fact that the ambassador and the subordinate (Mr. Sean Smith) were missing. According to Secretary Panetta’s statements to the Senate, the President “directed both myself and General Dempsey to do everything we need to do to try to protect the lives” in Benghazi.

General Dempsey recounted to the House Armed Services Committee:

The President instructed us to use all available assets to respond to the attacks to ensure the safety of U.S. personnel in Libya and to protect U.S. personnel and interests throughout the region.

Secretary Panetta and General Dempsey eventually returned to the Pentagon and guided the response from there.

“[A]s to specifics” of the U.S. reaction, Secretary Panetta testified to the Senate that the President “left that up to us.” Secretary Panetta said the President was “well informed” about events and worried about American lives. He and General Dempsey also testified they had no further contact with the President, nor did Secretary of State Hillary Clinton ever communicate with them that evening.

In short, President Obama told Panetta and Dempsey to do what was needed, and then retired for the evening. Vietor said last week that Obama and Clinton spoke by phone at 10 p.m., and that the president was in the private residence, not the White House Situation Room.

The president’s defenders can accurately state that the only way the president’s bedtime on the night of September 11, 2012, is relevant is if the military required his authorization for a particular act — say, entering Libyan airspace without permission from the host government. At this time, there has been no indication that was the case.

But even if the president’s bedtime wasn’t particularly consequential to the events on the ground on Benghazi, it certainly makes for an unflattering portrait of the president, heading to sleep as the battle raged, making sure he was sufficiently rested for the next day’s campaign rally in Las Vegas. This administration made sure the public knew how plugged-in and riveted President Obama was regarding the raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound. Leaving the response to the events in Benghazi to subordinates while he slept offers a portrait strangely disengaged, even callous, about the lives of the men who carry out his orders in dangerous lands. Obama’s absence from the Situation Room may not have been decisive, but it can still prove embarrassing and politically damaging.

We know where President Obama was the night of September 11, 2012, but not why he was where he was.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Jim Geraghty writes the Campaign Spot on NRO.