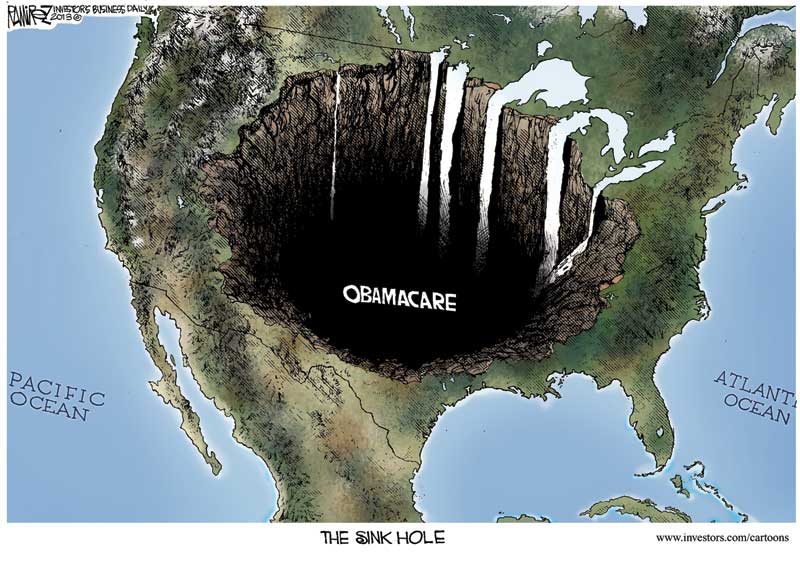

The “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act” (aka, “ObamaCare,” enacted in March 2010) is so “affordable” that more than 1200 companies (half the number) and unions (half the number) have sought and obtained partial waivers from its burdens and mandates. The U.S. Congress itself had the audacity to exempt itself from the law, a fact acknowledged only this week by the Office of Personnel Management (the federal government’s HR department).

Earlier this year the Wall Street Journal reported on “ObamaCare’s health-insurance sticker shock,” on how health insurance “premiums in individual markets will shoot up due to the mandates that take effect in 2014,” specifically: “requirements that health insurers (1) accept everyone who applies (guaranteed issue), (2) cannot charge more based on serious medical conditions (modified community rating), and (3) include numerous coverage mandates that force insurance to pay for many often uncovered medical conditions. . . . Insurers are adjusting premiums now in anticipation of the guaranteed-issue and community-rating mandates starting next year.” A more recent Journal report explains why premiums “could soar” (i.e., triple) even for the healthy under ObamaCare.

There’s ample evidence that the Obama Administration and most advocates of ObamaCare suspected this would happen; they intended to blame premium hikes on “greedy insurers,” then run them out of business after imposing profit-killing price controls, paving the way for their final solution: a “single payer” (fully nationalized) health care system. But the premium-hike shocks have arrived earlier than the ObamaCare pushers initially expected. They didn’t know insurers plan ahead. Fearing only a possible electoral fallout, Mr. Obama last month delayed the law’s implementation until 2015 – after the 2014 mid-term elections.

ObamaCare, most people realize, includes a “employer mandate” that requires all U.S. firms with 50 or more employees to provide health insurance for their full time employees, or else pay stiff penalties. That provision alone incentivizes small firms not to increase their employment beyond 49 people. Still, many won’t be able to afford ObamCare, such that in May the CBO estimated that firms will pay penalties (for lack of health insurance) totaling $150 billion over the coming decade, while individuals who elect to go uninsured will pay penalties totaling $52 billion. Less well-known is the fact that the law also defines full-time employment as 30 hours or more of work per week; by definition, part-time employment becomes anything less than 30 hours per week. If ObamaCare, truly, was not a real financial burden for employers, we wouldn’t observe any unusual resort by firms, of late, to the use of part-time versus full-time workers.

But the data show that U.S. firms are, indeed, using relatively more part-time employees – and more than usual, historically – as seen in the graph I’ve created (below), drawing on official U.S. data. Of course, there’s some cyclicality to this ratio: part-time jobs tend to decrease as a share of total employment during expansions and tend to increase amid recessions. Part-timers were just 18% of all U.S. employees before the recession of 2007-2009, but increased to more than 21% at the end of the recession. Even the sharp rise in the ratio during the recession seems excessive and is attributable, partly, to ObamaCare. After all, Mr. Obama was elected in 2008 and early versions of his scheme were passed in Congress in mid-2009.

The graph below shows that it’s quite normal for part-time work to stay high until an economic recovery takes hold and evolves into a full-fledged expansion; firms want to be sure an expansion will persist for at least a few years before they shift from part-time to full-time help. But my graph shows that the part-time share of U.S. employment has remained disturbingly elevated since the U.S. recession ended four years ago. Firms today seem as reluctant to hire more full-time workers as they are to part with huge cash hoards. The policy environment doesn’t seem hospitable to hiring or risk-taking. Based on past recoveries and recessions, by now the ratio of part-time to full-time employment should be moving much lower.

Although no definitive link can be established, it seems plausible that the elevated ratio of part-time to full-time employment is partly due to ObamaCare and what it promises to impose on firms and individuals. Notice that the only other outlier over the past three decades occurred in 1993, when the part-time employment ratio also spiked, amid fears Congress might enact HillaryCare. Not coincidently, HillaryCare had many of the same features that later would be embodied in Obamacare, including the arbitrary demarcations of the scheme applying to firms with 50 employees or more and the definition of full-time work as 30 hours per week. After HillaryCare was defeated, full-time employment boomed and the ratio of part-time to full time employment plummeted. People today who complain about the disproportionate number of lower-paying part-time jobs with no benefits, relative to higher-paying full-time jobs with rich benefit packages, might consider advocating the repeal of ObamaCare (or at least its 30-hour rule). Don’t hold your breath.

My analysis aside, I’d stress that the deeper problem with ObamaCare isn’t that it’s so costly (although it is), but the fact that it violates the principles of liberty (free choice). By claiming that “health care is a right” and emphasizing patient need above all else, it ignores or violates the rights of health service providers: doctors, insurers, drug firms, instrument-makers, and hospitals. In every socialized system, the real reason consumers end up suffering is because government starts out making sure producers suffer – and they do this because they believe the need of some creates a claim on the fruits of the labor of others. In their cost-benefit analyses economists should include the terrible cost of losing our precious freedoms.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Richard M. Salsman is a contributor to Forbes magazine. He covers the intersection of economics and politics.