By Susan Crabtree • Washington Free Beacon

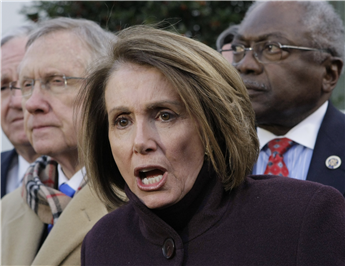

House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D., Calif.), who often rails against income inequality and calls on the wealthy to pay its “fair share” in taxes, took pains in late December to try to preserve tax breaks for two of her multi-million-dollar homes one last time before the new tax law kicked in.

Largely thanks to her husband Paul, a real-estate and venture-capital investor, Pelosi is the wealthiest woman in Congress with a net worth of more than $100 million and the seventh wealthiest member overall, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

In fact, assets and cash disclosed in her 2016 financial-disclosure statement places Pelosi in the top one-tenth of the 1 percent of Americans.

Pelosi’s annual property tax bill alone on three luxury homes last year—$137,000—is more than twice the 2016 U.S. median household income of $59,039, which the U.S. Census reported last fall.

Like most taxpayers, she also apparently wants to keep as much of her money as U.S. tax law allows, though she did not mention those plans during the contentious months-long debate on the GOP tax bill last fall or how it would impact her personally.

At the time, Pelosi accused Republicans and President Trump of hiking taxes on the middle-class while slashing those for corporations. She denounced the bill using apocalyptic terms, decrying it as “Armageddon” and “like death.”

At one point, she said the tax plan was a “monumental, brazen theft from the middle class,” and pledged that Democrats will continue to demand “job-creating, wage-raising tax reform with not one penny in tax breaks for the wealthiest one percent.”

Just days after President Trump signed the sweeping tax bill into law late last month, Pelosi and her husband tried to preserve $64,000 in property tax breaks, known as the state and local taxes (SALT) deductions, for her two California homes. The new tax law limits the deduction to $10,000 and went into effect Jan. 1.

Like many taxpayers with big property tax bills across the country, the Pelosis in late December prepaid the second half of their 2017-2018 property tax bills for their $7.2 million estate in San Francisco’s tony Pacific Heights and Napa vineyard and residence worth more than $4 million, according to San Francisco city-county and Napa county property records.

The couple paid the full annual property taxes on their luxury Washington Harbor condo on the Georgetown waterfront before the tax bill became law.

Paying the taxes earlier than the 2018 bills require is a smart accounting move that could save the Pelosis tens of thousands of dollars. However, it also illustrates a Republican talking point about the tax bill: that the new law is eliminating tax breaks that primarily benefit the wealthy.

Pelosi and her husband have owed roughly $137,000 annually in local property taxes on the three homes they use and don’t rent out: two in California and one in D.C., city and county property records show. Before the beginning of the year, they were allowed to write off all of those property taxes on their federal taxes but now can deduct only $10,000 of it under the new law.

The Pelosis could make up a good portion of the lost deduction through the new law’s provision lowering the tax rate on the highest income bracket from 39.6 to 37 percent. However, tax experts say they could still wind up paying thousands of dollars more to the federal government than in previous years because of the new law’s SALT deduction cap.

Pelosi spokesman Henry Connelly justified the pre-payment by arguing that it is legal and thousands of other Californians also tried to pre-pay their 2018 taxes in December.

“Millions of middle-class families and homeowners in cities and suburbs across America are facing a big state and local tax hike because of the GOP tax scam,” Connelly said in an emailed statement. “Any middle class family whose state and local income and property taxes add up to more than $10,000 will be forced to pay more—and many of these families also prepaid their property taxes before 2018 in hopes of staving off this GOP tax hike, including, for instance, 72,000 people in San Diego County alone.”

“This action is compliant with current tax laws and IRS guidance,” he added.

The sweeping changes to the tax law are hitting the Pelosis’ real-estate holdings particularly hard. Despite their wealth and assets, the couple still carries heavy mortgage debt.

Because all of their homes were purchased before 2018, they can still deduct the first $1 million in mortgage-interest debt on each home, but the Pelosis also have equity lines of credit on each of the three properties in question, totaling approximately $1.1 million to $2.25 million, according to her 2016 personal financial disclosure form, the latest available.

Under the old tax law, mortgage interest on the first $100,000 of each of those equity lines would be tax-deductible; the new law eliminates tax breaks for equity lines entirely.

Pelosi and her husband also own four other residential and commercial properties with a combined total value of $7.5 to $36 million and reported annual rental income of between $315,000 and $3,050,000 from them, according to her most recent financial disclosure report, which only provides broad value ranges.

The new tax law continues to allow rental owners to deduct their property taxes as part of the businesses’ expenses. The Pelosis sold two other California properties in 2016 and reported that they earned between $200,000 and $2 million in “capital gains/rent” from them that year.

Before January, there was no limit on the amount taxpayers could deduct on taxes paid to state and local governments, including property, income, and sales taxes. That policy, critics say, gave Democrat-run states an incentive to increase their taxes while citizens in other states with lower local taxes didn’t get the same tax benefit.

“The SALT deduction is really an unfair tax deduction. For a person who makes the same amount of money in Texas, California, and Tennessee, the person who lives in California or New York, or New Jersey gets a big tax break that the other people don’t get,” said Rachel Greszler a research fellow in economics at the Heritage Foundation’s Institute for Economic Freedom.

“It’s an issue of fairness, and [the previous law] encouraged states to raise their taxes and push the costs of running the federal government onto other states,” she added.

Pelosi has argued that capping the SALT deduction is “an insidious effort to raise taxes on the middle class.” However, most of the benefits of the tax break go almost entirely to top income earners, the bill’s GOP backers and other tax experts point out.

Only 28 percent of all tax filers in the United States claim the deduction, and nearly 90 percent of the tax break goes to those with incomes in excess of $100,000, according to the nonpartisan Tax Foundation.

Additionally, because the higher income earners pay more in state and local taxes, the value of the tax break sharply increases as income also rises.

The Heritage Foundation’s Greszler analyzed IRS statistics for California filers in tax year 2015 and found that only 34 percent of tax filers in the state claim the SALT deduction. The average SALT deduction for a California millionaire that year was $462,503 while the same tax break for someone earning between $75,000 to $100,000 was $7,931, well under the $10,000 cap.

Those deductions translate into a tax benefit of roughly $171,126 for millionaires in the highest tax bracket and just $1,745 dollars for those making $75,000 to $100,000, Greszler said.

Pelosi and her husband were hardly alone in trying to pre-pay 2018 taxes in the final days of last year. Thousands of taxpayers across the country with high property tax bills rushed to pay their bills at the end of December in the hope they could still take advantage of the far more expansive deduction before the new law took effect Jan. 1.

It is unclear if the effort will pay off: The IRS has said that localities must have already assessed the 2018 property taxes before the December payments in order for them to count.

Officials in the Golden State, as well as New York and New Jersey, where state and local deductions for taxpayers are the highest, are trying to rewrite their tax codes to reduce the impact of the new SALT-deduction limit.

In California, in particular, Democrats are getting creative. Kevin de Leon, the outgoing Democratic leader of the California State Senate who is challenging Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D., Calif.) from the left, wrote a bill that would create a state-affiliated California Excellence Fund. The fund, which the state would tap to pay for public services, would serve as a charitable repository for taxpayers to pay any property tax exceeding the new $10,000 cap. Federal law still allows an unlimited deduction for charitable donations.

Some tax experts are already predicting the work-around will fail because IRS rules generally ensure individuals who make charitable contributions aren’t doing so in order to gain a substantial windfall in return.

“To be deductible, charitable contributions must have a genuinely charitable aspect, and cannot primarily benefit the contributor or involve a quid pro quo. Payments which function as taxes may be classified as taxes even if states choose to call them something else,” Jared Walczak, a senior policy analyst at the Tax Foundation, wrote in a recent article.