by Kevin Sullivan • Washington Post

Mizanur Rahman sat in a coffee shop in Palmers Green, wearing a court-mandated electronic ankle bracelet beneath his long, black Muslim robe. British authorities consider him an Islamic State recruiter, so they closely monitor his movements and have taken his passport.

He is banned from meeting with more than two people at a time and must spend his nights under curfew at his home here in north London. Most difficult for Rahman, he is not allowed to touch any Internet-connected device.

Rahman is known for his loud and passionate online speeches extolling the Islamic State. He openly advocates for a global caliphate, a homeland ruled by Islamic law, which he says is a superior political, legal and economic system to democracy. He wants Britain to adopt Islamic sharia law, and he says the Islamic State’s black flag will one day fly over the White House.

Stirring a cup of milky Earl Grey tea, he said the militants will probably conquer Washington by military force, but he added that he does not necessarily advocate violence. Still, he argued, the concept of spreading Islam by force is no less honorable than Western countries invading Iraq or Afghanistan to spread democracy.

In a follow-up telephone interview last week, Rahman called the Islamic State attacks in Paris on Nov. 13 “an inevitable consequence” of French participation in coalition airstrikes against the militants’ de facto capital in Raqqa, Syria.

“I don’t think anybody should really be surprised at what happened,” he said. “In war, people bomb each other. I think it’s an opportunity for the French people to empathize with the people in Raqqa, who suffer very similar impact whenever the French airstrikes hit them — the civilian casualties, the shock, the stress. The anger that they must be feeling toward the Islamic State right now is the same kind of anger that the people of Iraq and Syria feel towards France.”

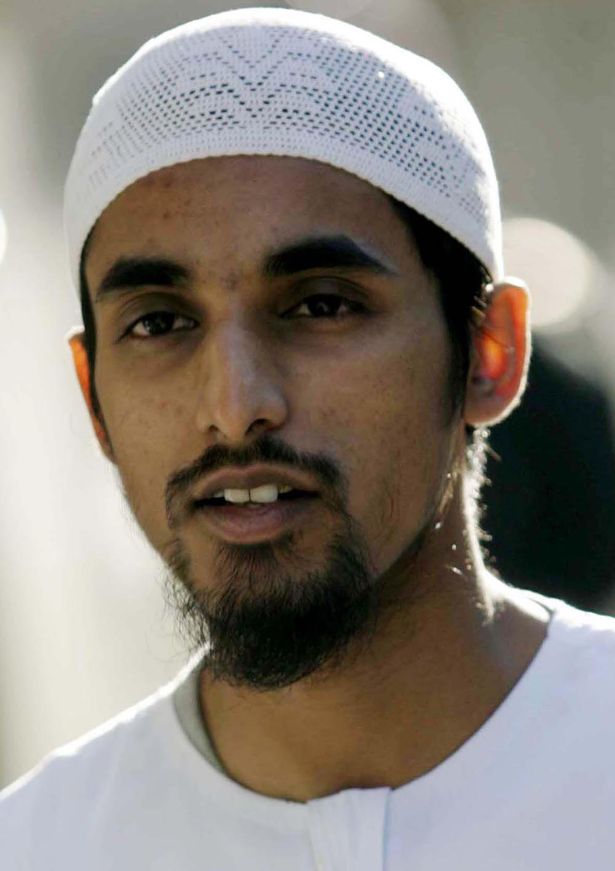

In person, Rahman is unimposing. Slightly built, he stands 5-foot-5 and has a wispy black beard. He is calm, articulate and charming — even as he argues that it is no worse for the Islamic State to behead American journalists than for the United States to kill Muslim civilians in drone strikes.

“I’m promoting sharia because I think it’s the best,” Rahman, a former accountant and Web designer, said in the London coffee shop interview. “I think it is better than what we have, and what is wrong with saying that?”

Plenty, say authorities in London and Washington. They believe the 32-year-old is a key figure in the world of preachers, teachers and true believers whose sophisticated online propaganda is critical to the Islamic State’s allure.

They says his thousands of tweets and Facebook posts, and fiery lectures on YouTube, are intended to inspire vulnerable young people — from London to Chicago to New Delhi — to join a militant group that beheads, crucifies, burns and drowns its enemies in the name of God.

In an online lecture last year that he posted on his YouTube channel, Rahman railed against the United States and exhorted Muslims to “wake up and unite behind the caliphate!” But he never specifically told anyone to commit violence.

“Stop playing games and sitting on the sidelines, watching: ‘Oh, the Americans are killing our brothers [in the caliphate]. I wonder how they’re going to do,’ ” he said, his voice rising. “Do something about it!”

In August, Rahman was charged in Britain with “inviting support” for the Islamic State, and he faces up to 10 years in prison if convicted. He is free on bail under strict conditions, including the ankle bracelet.

Western authorities said confronting the propagandists is critical to curbing recruiting and ultimately defeating the Islamic State, so they are trying to increase pressure on Rahman and other key proselytizers.

“He is dangerous because he creates the conditions where extremist ideology is seen as normal,” said Peter Fahy, the recently retired chief of police in Manchester, England, who has helped lead British anti-radicalization efforts. “He is just the start of the conveyor belt for people on a pathway to extremism.”

A senior U.S. counterterrorism official, who asked not to be identified in order to discuss sensitive intelligence matters, described Rahman as a “significant influencer” and part of an unofficial global network of Islamic State promoters.

In the coffee shop, Rahman called the allegations against him ridiculous and anti-Muslim persecution. He said that he has done nothing more than preach the virtues of Islam and that he has never specifically recruited anyone to join the Islamic State or urged anyone to commit violence.

“I’m not recruiting for ISIS. I’m not part of them,” said Rahman, a London native who speaks in perfect, British-accented English. “This is McCarthyist. If you have a different ideology of how the government or country should be run, then you are attacked or targeted as a terrorist.”

Rahman’s case illustrates the challenges of trying to prosecute Islamic State promoters in nations that prize free speech: How do governments stop savvy, careful people from exploiting the gray area between free expression and inciting violence?

“He walks you to the cliff, and you’re supposed to decide yourself whether to take the last step — and that’s been incredibly difficult to deal with by the authorities,” said Peter Neumann, head of the International Center for the Study of Radicalization at King’s College in London.

Neumann said Rahman is one of a few key “lighthouses” on social media, acting as beacons for vulnerable people who are looking for answers. He said Rahman is skilled at persuading Muslims that it is their religious obligation to swear allegiance to the Islamic State leader, arguing that God wants the world united under a caliphate — without ever overtly calling for them to move to Syria or Iraq.

“If you take it all together it clearly amounts to making the case for going there, but he will not say, ‘Go there,’ ” Neumann said.

Rahman has not always managed to stay on the right side of the law. He served two years in prison in Britain, from 2006 to 2008, for a speech he gave condemning a Danish newspaper’s publication of cartoons of the prophet Muhammad. At a rally, he said that he wanted British soldiers “coming home in body bags” from Iraq and that “we want to see their blood running in the streets of Baghdad.”

Rahman said he stood by those comments but said they came at a “charged” moment when Muslims all over the world were feeling attacked because of the cartoons and the Iraq war. He said beseeching God for British soldiers to be killed in what he considered an unjust war against Islam was inflammatory but did not amount to inciting violence by insurgents in Baghdad.

“I don’t think they take their policies from a 22-year-old boy, who nobody knows, at a demonstration in London,” Rahman said.

To the frustration of British authorities, Rahman has become a rock star on social media since his stint in prison, and he has become more careful about the law as he pumps out a nonstop gusher of words promoting the caliphate.

Asked if he liked to “play” with the line between legal and illegal speech, Rahman smiled and said, “That’s a good characterization of exactly what I do.”

“I tend to know the law better than the police,” he said.

‘The crown prince’

Just as British police accuse him of radicalizing young Muslims, Rahman himself was deeply influenced by an older Islamist preacher.

Rahman was born in London in June 1983 to immigrant parents from Bangladesh and grew up playing basketball, listening to pop music and playing video games. His family was Muslim but not very religious, and he attended local Protestant schools run by the Church of England.

His father, an engineer, began pressing Rahman in his teens about what he wanted to do with his life. He urged him to study medicine like his brother or become a lawyer — neither of which appealed to him. He felt aimless until one day in January 2001 when, at age 17, he met Omar Bakri Mohammed.

The Syrian-born Bakri would later become one of London’s most famous Islamist preachers, and in 2004 he vowed that Muslims would give the West “a 9/11 day after day after day.”

Bakri was a driving force behind two extremist groups that were eventually banned by the British government: Hizb ut-Tahrir and al-Muhajiroun. He is in prison in Lebanon, where he sought exile after being refused reentry into Britain in 2005 because his presence was deemed “not conducive to the public good.”

When Rahman first saw Bakri speak in a mosque near his childhood home in Palmers Green, he was inspired.

“I found a whole world of Islam. I saw how vast it was, how incredible it was,” Rahman said. “I just realized I had wasted my whole life in education learning stuff that was useless to me, drawing pictures in art. There is something to be said about art. I still enjoy it, but it’s not what’s important in life. It doesn’t answer the meaning in life.”

Rahman scrapped his plans to go to university and instead began an intensive five-year course of study with Bakri. Rahman said that gave him a deep well of knowledge, and he now considers himself an expert in Islamic theology and sharia law.

“Islam is more than just a book with an old story. It’s actually a code for life,” he said, adding that Islam is a blueprint for everything from personal hygiene to international relations. “It’s not just some medieval rantings.”

He said his father was worried when he started speaking out publicly with his newfound zeal and conservative clothing, predicting that “the government is not going to like it.” He was quickly proved right.

Rahman’s first arrest was in February 2002, when he was fined 50 pounds for defacing posters for a pop band that featured scantily clad women, something he considered indecent.

In the spring of 2005, during a general election campaign, he was fined again for plastering signs that said “Muslims don’t vote” on the headquarters of the Labour Party. In his view, Muslims should not accept any man-made laws or participate in any form of government other than one run by sharia law.

By the time he was sentenced to prison in 2006 after publication of the Danish cartoons, he was already becoming an inspiration to other radicalized Muslims. A young Nigerian convert to Islam, Michael Adebolajo, was arrested for attacking two police officers outside the Old Bailey courthouse during Rahman’s trial.

In 2013, Adebolajo and another man murdered British soldier Lee Rigby, nearly decapitated him on a London street.

“The most important thing I learned in prison was to be patient,” Rahman said. “Patience is really underestimated. You learn to deal with things, to endure.”

Analysts see a generational shift happening among the most outspoken radical preachers in London, which has in recent years been one of the world’s centers of English-speaking Islamist proselytizers.

Neumann said the chief heir to Bakri is Anjem Choudary, who also studied under Bakri for years and has been a close friend and mentor to Rahman.

But now that Choudary is nearing 50, Neumann and other analysts said, the torch is being passed to Rahman. They said he represents the rising generation of tech-savvy disciples who are steeped in social media and youth culture, carrying on Bakri’s message and using modern tools to inspire young people.

“He is the crown prince,” Neumann said.

Rahman’s reach is global: An Indian woman, Afsha Jabeen, under investigation for allegedly promoting the Islamic State, told Indian authorities that she had followed Rahman’s speeches and writings, according to Indian news reports.

After the Islamic State declared its caliphate in June 2014, Rahman used his online lectures to celebrate those who had been “spilling their blood” and “fighting jihad” to establish the first caliphate since the Ottoman Caliphate was abolished in 1924.

“For the past 90 years people have been waiting for the caliphate,” he said in a July 2, 2014, lecture posted on YouTube. “Some people have been waiting, and some people have been working for the caliphate. This is the difference between the one who has just been sitting and waiting in the mosque, praying and hoping for it to come from the sky, and those who have been sacrificing and spilled their own blood, their health and going to prison, traveling the lands, fighting jihad, working to establish the caliphate on Earth!”

Rahman said he, too, would love to take his family to the caliphate, but he complained that British officials have taken his passport.

‘I speak as a duty to God’

On Thursday, Aug. 7, 2014, Rahman was on his computer pumping out his usual flow of tweets and Facebook posts. He mocked the United States, tweeting, “People have been watching too many hollywood movies they think USA is undefeatable.”

As he sat in London, a message arrived from @lionofthed3s3rt, the Twitter handle of Mohammed Hamzah Khan, an American teenager in suburban Chicago.

Khan, 19, was thinking about traveling to Syria with his younger sister and brother to join the militant group. But first he had a question for Rahman about the Islamic State’s self-proclaimed caliphate.

Using a mix of Arabic and text English, Khan asked Rahman whether it was enough to simply preach about the caliphate if Muslims weren’t ready to join: “what do u say [to] the ppl who claim [that preaching] is more important right now?”

Rahman’s response was immediate and forceful, and over the next 40 minutes he sent eight tweets back to the teenager, telling him that it was his “duty” as a Muslim to “accept” and “obey” the “caliph” — Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi: “it is [necessary] to declare and give [an oath of allegiance] immediately.”

Rahman’s tweets offered religious justification for swearing allegiance to the caliph. None of them specifically urged Khan to go to Syria, and he added that swearing allegiance was a matter of “each according to our own capability.”

Less than two months later, Khan and his younger siblings, 17 and 16, were arrested at O’Hare International Airport en route to Syria. Khan pleaded guilty last month to providing material support to a terrorist organization and faces up to 15 years in prison.

Charlie Winter, a researcher at the Quilliam Foundation, said the tweets fit perfectly into Rahman’s pattern.

“He is supplying the ideological justification for joining a group like this,” Winter said, adding: “It makes the person he’s speaking to feel special because he’s very prominent. The accessibility of notable cheerleaders of the Islamic State makes their outreach strategy a lot more effective.”

In the London coffee shop, shown a printout of his tweets with Khan, Rahman said he remembered the exchange. He noted that nowhere does he tell Khan to go to Syria.

Rahman was asked how he felt that within two months of telling Khan to swear allegiance to Baghdadi, the young American tried to travel to Syria.

“I’m indifferent,” Rahman said. “I’m not answering questions in order to try and inspire people or anything like that. I speak because of Islamic duty. I speak as a duty to God.”

Rahman said he feels no guilt about Khan’s arrest.

“I have nothing to feel guilty about at all,” he said. “I’ve been asked a question, I’ve answered a question. If that inspires you to then go live there, that’s up to you.”

Rahman was arrested in September 2014 on charges of “encouraging terrorism” and belonging to a banned group; he said he was never informed which group. He was arrested along with Choudary and his childhood friend Siddhartha Dhar, also known as Abu Rumaysah.

Shortly after the arrest, Dhar jumped bail and secretly fled Britain with his wife and young children. In November 2014 he tweeted a photo of himself in Syria, holding his newborn son in one arm and an assault rifle in the other.

Rahman had introduced Dhar to Bakri and encouraged his conversion to Islam. Now Dhar is a prominent online spokesman and propagandist for the Islamic State, and his old friend cheers him on via Twitter.

Two months ago, British authorities took Rahman and Choudary back into custody and added new charges of “inviting support” for the Islamic State through lectures that were published online.

After a month in jail, Rahman is now free on bail. He said that he once had small businesses helping people with accounting and Web design but that his notoriety makes it impossible to find customers. He and his wife, and their three young children, have moved back in with his mother in the small rowhouse where he was raised.

The government of Prime Minister David Cameron recently announced a new crackdown on extremism and those who radicalize people. The government has been cheered by many, but also criticized for seeking security at the expense of free speech and other long-cherished personal liberties.

“We see the frustration in their eyes: ‘These guys don’t break the law, so how can we stop them?’ ” Rahman said. “I think there was a lot of pressure to say, ‘Look, we need to charge these guys with anything.’ ”

Doug Weeks, a visiting research fellow at London Metropolitan University who has interviewed Rahman and Choudary extensively, said their prosecution will be the “ultimate test case” as Britain tries to balance security and free speech.

“This trial could be a watershed moment in U.K. law,” Weeks said.