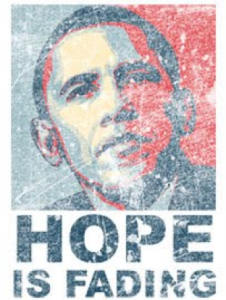

For many American voters Barack Obama has lost his air of can-do heroism

“He is an extremely solitary man. He is the most introverted president we have seen in the United States for decades. Barack Obama sits alone in his presidential study, up in the White House, for hours at night, writing and thinking and looking at memos and processing.”

by Andrew Marr

So [Superstorm] Sandy arrived right in the last act, smashing and thrashing, killing and ripping. Has this latest tempestuous eruption, following the storms Beryl, Florence, Joyce and Nadine, been the deus ex machina — or the deus ex Atlantic — to settle one of America’s most extraordinary and bitterly fought presidential elections?

It won Obama a gold-plated endorsement from one of America’s most popular Republicans, the New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, who fears that climate change is to blame; and an embrace from another admired Republican governor, Chris Christie of New Jersey.

But will the Sandy Effect really sway votes in swing states thousands of miles away? Obama has not had a good campaign. His hugs and his rousing words after the hurricane were one thing, but his low-energy, stumbling performance in the first presidential debate left supporters aghast and Mitt Romney’s team suddenly emboldened.

It has been a savage campaign, and for good reason. America’s culture wars have never been angrier. The country remains mired in debt — $16 trillion, up $6 trillion under Obama — of which $1.4 trillion is owned by America’s new existential rival, China. The US Treasury says that the legal debt ceiling will be hit by the end of the year.

Jobs have been exported in huge numbers. The middle classes have been getting poorer for years. Only the super-rich have experienced a rise in real incomes.

As a passionate admirer of the US, I have to admit that to visitors, America no longer feels quite like the future. There are the potholed roads, tired-looking airports and malls, and what seems from a British perspective a strange dearth of wi-fi. Natural disasters aside, this is beginning to feel like a nation needing a lick of paint.

I went with a film crew from President Obama’s home base of Chicago, through Washington and New York, talking to people who knew him and to some of his sharper critics. We carried with us a simple question: whatever happened to hope? How could someone so gifted as a speechmaker, with such a tailwind of popular enthusiasm behind him, fall so far in public esteem?

This isn’t a partisan question. It is being asked by Democrats, still smarting from their terrible 2010 Congressional mid-term drubbing, as well as by Republicans. Yes, some of the anti-Obama rhetoric has been grotesquely over-the-top — all the stuff about him being a secret Muslim, and not really American-born at all. But middle-of-the-road, once pro-Obama people are puzzled too.

Artur Davis, a black former Congressman from Alabama who was one of the co-chairs of Obama’s 2008 campaign, later switched to the Republicans and spoke for Mitt Romney at their convention this year.

He thought Obama had “made the best first impression of anybody in American politics for perhaps 40 years” but was, from the first, too vague: “He did a very good job painting a picture of politics without necessarily filling in the canvas with a lot of policies.” We in Britain have had a little experience of that, too.

Part of the answer goes back to the consequences of the banking crisis when Obama was first elected. Talking to Austan Goolsbee, the Chicago economist at Obama’s side during the 2008 campaign and the first period in office, you get a vivid picture of the near panic as atrocious figures poured in. It wasn’t simply Wall Street in trouble. There was a pervasive sense that US capitalism was facing a crisis at least as big as that of the Great Depression.

At one point, after another terrifying round-table of economic briefings, Goolsbee said to President-elect Obama that he thought no president since Franklin Roosevelt in 1932 or perhaps Lincoln in 1861 had faced such a grim background briefing. Obama looked at him and said, “Goolsbee, that’s not even my worst briefing this week.” By pouring money in, a giant financial boost, many believe that Obama saved America from economic collapse. But there are plenty of others who question whether it was the right boost, or produced the right effect.

Republicans, of course, argue that he should have slashed taxes further, and cut back the state.

Nothing has divided the US as deeply as the so-called “Obamacare” changes to health funding. What seems from a European perspective a civilised amelioration of injustice in the hugely expensive US health market, feels to millions of Americans like a socialist big-state intrusion into their personal affairs.

We spoke to people on all sides — Chicago Republicans who felt that an inexperienced President “in over his head” had been so obsessed with his healthcare mission that he had taken his eye off the economy, and Democrats baffled by the fury that such a moderate change had brought.

Two things at least became clear. The first was that both sides were no longer hearing each other — Democratic America and Republican America increasingly live apart both geographically and mentally, tuned into different media giving them a different view of the world.

Perhaps there is nothing much that Obama could have done about that. But the second conclusion, shared on almost all sides, is that he proved a very poor persuader in his own case. The first presidential debate rammed that home. Good at soaring speeches; less good at looking voters in the eye and winning them over on the detail. Pulpit, yes. Bear pit, no.

After a storming speech at the Democrats’ national convention, Bill Clinton has been criss-crossing the country showing how it’s done — so much so that a rueful Obama describes him as “the Secretary for Explaining Stuff”.

Obama has never been a very convincing glad-hander. All those who mocked Clinton’s cheesy gregariousness are being forced to reconsider. Jodi Kantor, one of Obama’s biographers, told me that although the President is formidably intelligent, he may over-rely on it: “He is an extremely solitary man. He is the most introverted president we have seen in the United States for decades. Barack Obama sits alone in his presidential study, up in the White House, for hours at night, writing and thinking and looking at memos and processing.” Such self-certainty has allowed him personally to authorise the drone strikes that have killed so many — to the dismay of his liberal supporters — and to authorise the killing of Bin Laden, still his most popular act in office.

But it also led Obama into his early bout of over-promising — the announced closure of Guantánamo Bay, which later proved impossible because of political hostility to a new site on US soil, and the belief that just by being elected he could bring a new era of trust and peace between America and the Muslim world.

But if this were only a story of personality, and traditional divisions between Right and Left, it would be a less momentous election.

The truth is that America faces huge challenges to modernise its economy, dealing with debt, joblessness, infrastructure and inequality. It is impossible to avoid a sense of almost existential insecurity, very dark shadows in the still-bright American dream.

That will mean harder choices by far than either Obama or Mitt Romney have articulated in the campaign.

The economist Jeffrey Sachs blames Obama for the lack of real change being offered to a country that, for all its dynamism and talent, is not in good shape. He goes back to the original stimulus. “Starting from a $1 trillion deficit at that point, the Government was proposing to raise it to about $1.5 trillion and I thought, that’s rather shocking. What’s the plan?”

Obama came in at a tough time and has faced a divided country, uneasy about its role and future. Republicans in Congress never cut him much slack and after the 2010 mid-term elections he was hamstrung. Then again, he hasn’t proved good at winning arguments or reaching across the divide.

This has caused a rethink among Democratic strategists. Cornell Belcher, the black pollster who helped to create Obama’s 2008 movement and is a strategist for the current campaign, complains that “there is an unprecedented level of disrespect for this president. And they know it’s because he doesn’t look like any other president we’ve ever had”. Is this about race, I asked him. “Yes, but also about culture — about a group of people who are uncomfortable with the changes happening in America.”

This drove Obama to lean on his core vote and indulge in attack ads on Romney of a kind he abjured four years ago. They don’t seem to have had the lethal effect his strategists hoped for. Another Democratic pollster, Anna Greenberg, feels that middle-of-the-road voters simply don’t regard Obama as the miracle-worker he once seemed: “People like him but they don’t love him the way they loved him in 2008. He’s a human being now.”

He is hardly the first leader to over-promise, then under-deliver. I met plenty of people still illuminated by the half-light of “hope”, who still think that in a second term Obama will bring real change. He remains a symbol of America’s great ability continually to reinvent itself.

But charisma can’t get bills through Congress, or win the big arguments. It’s fine to believe in revivalist rhetoric and miracles; less fine if you choose to worship a politician.

Andrew Marr is a British journalist and political commentator for The London Telegraph.