When we limit students’ ability to discuss controversial ideas, we allow harmful prejudices and thoughts to fester. Classrooms should offer more.

By Jonathan Helwink • The Federalist

In his seminal work, “The Closing of the American Mind,” Allan Bloom recalled having a debate with a colleague about education. During the debate, the colleague said that his duty as an educator was to get rid of his students’ prejudices. Bloom wondered: Would his colleague render his students passive, indifferent, and subject to authorities like himself? Or was he just showing off?

Bloom’s response: he said he tried to teach his students prejudices. Prejudices, to Bloom, were avenues to knowledge. Error is the enemy, but error points to the truth, and therefore deserves our respectful attention. This notion is undervalued on college campuses, where increasing numbers of students learn to become citizens in a republic. But Bloom’s method could point to a new way forward for free expression on campus.

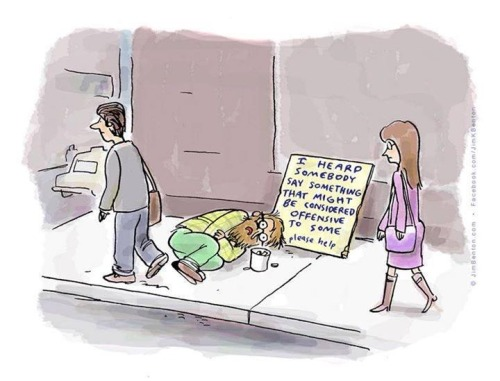

Error seems to be everywhere on campus, and there is no shortage of people willing to clamp down on it. Speech that is deemed offensive or prejudicial by campus activists and college administrators must be stamped out. But this approach is mistaken. It injures the students and our democracy. Error is not the insulting or assaultive speech—it is the prejudice behind the speech. When certain speech is punished, or forbidden by trigger warnings or safe spaces, students are not constructively confronted about their (alleged) racism, sexism, et cetera, through reasoned argument. Instead, they are silenced through intimidation and threatened punishments. In the meantime, the erroneous thoughts are not displaced; instead, they persist without challenge.

Why the Class Room Should Be a ‘Safe Space’ For Debate

I believe that a classroom possesses unique qualities that separate it from the rest of a college campus. This approach, referred to as the “classroom-quad distinction,” states that a college can regulate speech that it deems offensive outside the classroom. Speech in common areas on campus—lawns, hallways, dorms, and concert halls—may be regulated more heavily by the college because of the communal nature of these spaces. Students, especially those from historically under-represented groups, deserve to feel they are full members of the college community. They should be confident in the belief that no matter their background, heritage, faith, gender, ability, or race, their college values them. Regulation of common areas on campus achieves this end.

Regulation, however, would not be possible inside the classroom. The classroom should be a welcoming environment for debate, an engine by which closely held beliefs are challenged. It should be a stage for the unscripted drama of confronting the past and the present. With the aid of a good professor and the proper atmosphere, the classroom can be the incubator of ideas deemed unacceptable, subversive, treasonous, and even those yet un-thought, while still creating an environment of equality and understanding.

This is not to dismiss some of the arguments made in favor of safe spaces and trigger warnings. It is a mistake to brush aside the students, professors, or institutions that use these practices, saying they’re indulging “delicate snowflakes” or accusing the colleges of caving to leftist activists. The compassion and empathy the advocates of these policies emphasize should not be so easily disregarded. Some students, such as those who are victims of sexual assault or suffer from PTSD, make reasonable arguments for their positions.

However, while there is value in empathizing with students, we should not allow a student’s personal history to act as a muzzle on the classroom. Special arrangements for sensitive students have a negative impact on academic progress, and alternative assignments undercut the value of confronting and studying controversial topics and material. Despite the difficulties, it is possible to respect the victims of traumatic events while creating classroom spaces where the free expression—of even the most erroneous ideas—is respected and protected.

The History of the University Classroom

The classroom-quad distinction has as its basis the history of American higher education. Dating back to the earliest colleges in the colonies, the historical record shows that, even before the passage of the First Amendment, free expression in the classroom was respected, while behavior and speech outside of it was regulated by college administrators.

Colonial colleges were, most often, founded by dogmatically religious sects that were very strict in their regulation of student behavior. In 1744 at Yale, a college founded as a “safe, sound institution where the faith of the fathers was carefully protected,” two students were expelled for attending a religious revival while on vacation with their parents. Benjamin Homer Hall’s list of fineable offenses for 18th century students at Harvard College provides punishments for student behavior ranging from tardiness at prayer and entertaining persons of “ill character” to frequenting taverns and firing guns in the college yard. At the College of William and Mary, faculty were often required to take oaths of loyalty to the king and the Church of England before they accepted a faculty appointment.

The history, however, does not provide evidence that a similarly dogmatic approach to free expression was in place inside the classroom. While the pilgrimage from Harvard to New Haven cannot be dismissed, it is important to point out that the reason behind the exodus from “godless Harvard” was the tolerance of differing ideas in Cambridge, where, according to historian Frederick Rudolph, a spirit of honest disagreement between Puritan believers was allowed to flourish. In fact, the historical record shows that while colonial students attended required religious classes, they also attended lectures on Copernican theory, Newtonian physics, and other discoveries of the Scientific Revolution. Robust student debate was commonplace. Expressions that could get a student in trouble outside the classroom were encouraged inside of it in the name of academic inquiry and communal progress.

The Classroom Should Confront and Hone Student’s Ideas

True academic inquiry demands an environment of mutual respect, which, in turn, requires the recognition of another’s innate human dignity and worth. At the same time, respect for ideas that an individual may find personally disagreeable—including the hurtful, unsubstantiated, and flat-out wrong—is required as well. The best professors make it a priority to challenge students, not to fill them up with different, preferred prejudices. At the same time, professors should not seek to steal a student’s prejudices away, like Bloom’s colleague, but rather to expect each student to explain themselves and defend their position instead of reprimanding them for being wrong, forbidding them to speak, or forcing them to hide their opinions.

Trigger warnings and safe spaces do not address the errors of insulting or assaultive speech. Rather, these practices mask student opinion with a thin glaze of political correctness. Students are not convinced by their activist colleagues that their Halloween costumes are offensive, or that voting for Donald Trump is wrong. Instead, students are intimidated into silence. Erroneous thoughts persist and fester as a result. In keeping with the traditions of American higher education, the most efficient way to address error is to bathe it in the sunlight of the marketplace.

First introduced by British philosophers John Milton and John Stuart Mill, the marketplace of ideas theory posits that a robust debate, unencumbered by government action, will lead to truth, or at least, the best available option. This theory was introduced into American common law by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’ famous dissent in Abrams v. U.S. Justice Holmes wrote, “The best test of truth is the power of thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.” In the real world, however, the marketplace is not what Justice Holmes wished it to be. Critics have pointed out that the real marketplace suffers from systematic imbalances, such as uneven access to communication technology, monopolistic control of media outlets, and limited access for minority interests, among others.

What a Classroom Marketplace Should Offer

These imbalances do not have to be true of a classroom marketplace. Inside a classroom, students can approach a debate as equals, knowing their equal ability to be heard will be protected. They’ll know they are equally subject to the forceful rejection of their conclusions and the possibility of being deeply offended by the speaker’s response.

The professor has a role to place in this marketplace as well. Like the moderator in Professor Alexander Meiklejohn’s town hall meeting analysis, the professor’s responsibility is to facilitate debate, while maintaining a level of decency and decorum. Under this framework, which Meiklejohn drew from the structure of town hall meetings, the classroom would require each student to meet as a political equal, each with the right and duty to express their thoughts and to listen to others’ arguments. The students are guided by the professor, acting as moderator, who opens the debate and arranges student conduct under certain rules.

Admittedly, this special conception of the classroom may not satisfy the concerns of the strictest trigger warning and safe space advocates, who would likely contend that the possibility of potential harm is not sufficiently considered. Meiklejohn would respond that free speech includes the notion that all ideas must have their hearing, the unwise and the wise ones, the dangerous as well as safe, the un-American and the American. In addition, for the classroom to function properly, it must be understood that the classroom environment requires certain characteristics, governed by the parameters of the First Amendment on one level, and by standards of decency and decorum enforced by the professor-moderator on a second level.

Error Points the Way To Truth

Trigger warnings and safe spaces don’t solve the problem of harmful speech. Error, in this context, is not the assaultive speech, but the prejudice behind the assaultive speech. When certain thoughts are forbidden, the erroneous thought goes unaddressed and is, consequently, allowed to fester. In the name of saving an oppressed minority from harm, a far greater harm—allowing the furtherance of discriminatory and hateful opinions—has been carried out in society. The classroom-quad distinction drags those harmful opinions out into the daylight and exposes them for what they are: error.

In this open exchange, the classroom learns two critical lessons: 1) the realities of the issues addressed, and 2) how to respectfully confront someone you disagrees with. This method does not pick a side between a speaker and a listener and it doesn’t make a hero out of a bigot. Instead, within a welcoming and moderated environment, this method arms the students with the knowledge to confront an erroneous idea, and with the skills to artfully challenge ideas they disagree with.

Free exchange in a college classroom is critical to the development of a young mind’s sense of identity, a student’s experience with democracy, and to the cultivation of rational argument. But real harm can be inflicted on students by assaultive speech, and so regulation of expression outside the classroom is needed to create a safe and welcoming environment for students of all backgrounds. These necessary lessons can be fostered by drawing a classroom-quad distinction.

Meiklejohn argued that no citizen should be stopped from speaking because their views were thought to be “false or dangerous.” As Professor Bloom suggests, error is the enemy, but error points the way to truth. That truth can be discovered through the free exchange of ideas. As more students attend American universities, it is imperative that the virtues of democratic debate are nurtured in the incubator of a college classroom.