Former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg and former Massachusetts governor Deval Patrick recently jumped into an already crowded race for the Democratic nomination. Politically, they hope to appeal to center-left voters rightly worried about Joe Biden’s flagging early-state poll numbers. Ideologically, they have cast their candidacies as efforts to save a fading breed of centrist Democrat. Neither Bloomberg nor Patrick is likely to win. Instead, for the first time in recent memory, two leftist candidates stand a good chance of seizing the party’s nomination: Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, and Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts.

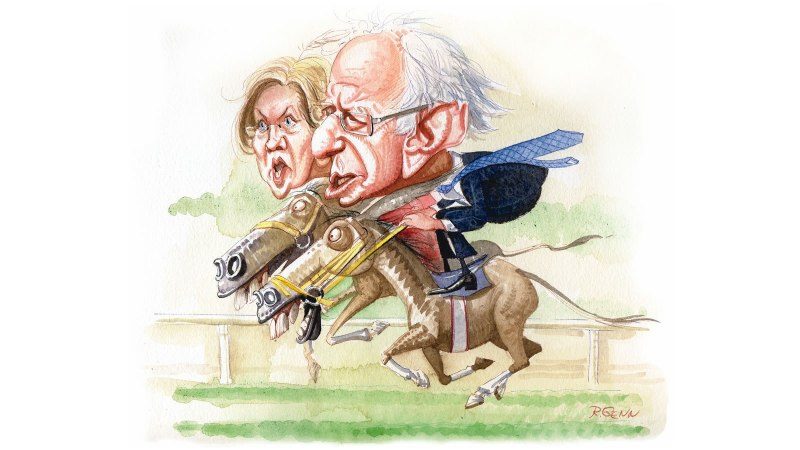

To many observers, Sanders and Warren closely resemble each other. They represent solidly blue New England states, advocate the nationalization of large parts of the economy, and believe that the ills afflicting society result from a political process hijacked by the wealthy few. Yet Sanders and Warren are hardly interchangeable. Despite shared policy goals, they differ in their coalitions, diagnoses of what ails America, theories of change, and, ultimately, prospects in the general election next November.

The Democratic primary electorate is sharply divided by race, age, and gender. The left wing of the party — younger, whiter, and more female — is overrepresented in the Iowa caucuses. Indeed, while national polling suggests that Sanders has a more racially diverse coalition, and that he does well among younger men, Warren is stronger among women of all ages and college-educated white liberals.

Iowa is a do-or-die test for Warren and Sanders; should either win the Hawkeye State, he or she will be the odds-on favorite to win in New Hampshire, where both enjoy a home-field advantage as New England senators. Organizationally, the Iowa caucuses are a monster. Caucuses take place in the dead of Iowa’s notoriously severe winter and feature runoff voting at each of the state’s 1,681 precincts. A viable campaign needs representatives ready to speak at each caucus and trained to court supporters of candidates who fail to hit the 15 percent viability threshold in the first round. The state, and therefore the nomination, may hinge on whose caucus leaders are better trained.

Warren has lately given Sanders a chance to highlight their ideological differences. On Medicare for All, Sanders has bluntly and repeatedly promised to raise taxes to pay for universal coverage. Taxes will go up, he contends, but costs will go down and Americans will no longer have to worry about losing coverage or wading through a morass of paperwork. Warren, by contrast, has promised to give free health care to every American without raising taxes on the middle class.

Setting aside whether any Medicare for All plan is realistic, Warren’s no-tax promise suggests to many on the left that she lacks the resolve to force through a politically difficult reform and would cave to conventional wisdom. Indeed, leftists have reasons to doubt her commitment. She refuses the label “socialist,” was a Republican earlier in life, and has generally tacked closer to the Democratic mainstream than Sanders has. Some of her struggles with candor raise questions about her character. Warren has never satisfactorily accounted for her multi-decade deployment of imagined Native American heritage for personal and professional gain, for instance. Making an obviously false but politically expedient promise — free health care with no middle-class tax increases — reinforces the impression that Warren is not trustworthy.

Warren’s no-tax plan also undermines her credibility with the press, which has heretofore dutifully relayed her self-presentation as a sophisticated thinker, policy wonk, and technocrat with a plethora of Ivy League–certified schemes. Many of her lower-profile plans will not hold up to scrutiny. If the press comes to see her as a phony, she might have to deal with a running series of bad stories about the unviability of her white papers. Sanders, whose messaging has always been high-level and simple (even simplistic), has not offered much in terms of specifics, but as a result he has a minimal paper trail to defend.

Yet these differences go beyond taxes and messaging. They go to a fundamental tension on the American left. Warren comes from the progressive tradition of the Left, whereas Sanders is a legatee of its populist tendencies. Being a progressive first, Warren prefers the technocratic approach. For her, simmering left-wing populism can be used best to attack entrenched power, by electing a president who will fill the bureaucracy with like-minded experts and pass campaign-finance reform to limit corporate influence. In other words, personnel is policy.

Sanders believes that American government is fundamentally broken. In a divided constitutional system, elected officials and regulators alike will be corrupted by special interests and will default to the status quo unless compelled to act otherwise. Control of the bureaucracy is not enough. Rather, for his “political revolution” to succeed, Sanders needs a movement that will last beyond Election Day and exert political pressure on the elected officials and regulators. Absent a confluence of movement, party, and administration, special interests will prevent the passage of sweeping structural reforms.

Put simply: Warren wants to regulate, Sanders wants to legislate.

Whether that distinction will matter electorally come November is unknowable today. However, we have some evidence on which to hazard a guess. First, the national demographic polls mentioned above, irrelevant in a staggered presidential-primary process, come to bear once the parties have picked their nominees. There are very few prospective Elizabeth Warren voters who did not pull the lever for Hillary Clinton in 2016. A replay of the last presidential election might be enough for Warren to win in 2020, especially given heightened Democratic turnout in elections since 2016. However, Democrats suffered from low minority and youth turnout in the Upper Midwest in 2016, and it cost them the presidency.

Sanders does well with precisely the voters who stayed home when Hillary Clinton topped the Democratic ticket. Younger and more diverse voters were essential to his victory in the Michigan primary, for instance, and while primaries are not the same as general elections, they serve as decent indicators if Democrats need elevated turnout to win. Sanders would get more non-voters to the polls than Warren would, and there are few voters who would vote for Warren but not Sanders.

Sanders has overperformed the Democrats’ partisan vote-share in Vermont, whereas Warren has generally undershot other Democrats in Massachusetts in polling and at the ballot box. Admittedly, Warren represents a state many, many times the size of Vermont. Nonetheless, her underwhelming approval ratings at home suggest that she lacks crossover appeal to independent voters. This is especially true in western Massachusetts, which, like many parts of Vermont, resembles the rural and exurban parts of the Upper Midwest that turned out heavily for Trump and doomed Clinton’s candidacy.

Neither Sanders nor Warren would enter a general election without baggage, and both would have to face a messaging onslaught from President Trump. Incumbent presidents tend to get reelected. Combine that with good economic performance, peace abroad, and wage growth, and Trump, despite his unpopularity, stands a good chance of winning a second term, provided there are no major changes in the next twelve months. However, 2016 was won on the narrowest of margins. When we look at only those states that were decisive, Sanders appears as a bigger threat to Trump than Warren does.