STANFORD – After years of rumblings for change in US education, the COVID-19 pandemic is becoming a catalyst for improving the system. America’s educational divide – especially in grades K-12 (elementary through high school) – is now clearly visible for anyone to see. Disparities in quality and access to education are a major source of the economic, social, and racial inequalities that are driving so much social unrest from Austin and Oakland to Portland and Seattle. Whether they come from impoverished inner-city neighborhoods or the suburbs, the least-educated Americans have been the hardest hit by the pandemic and its economic effects.

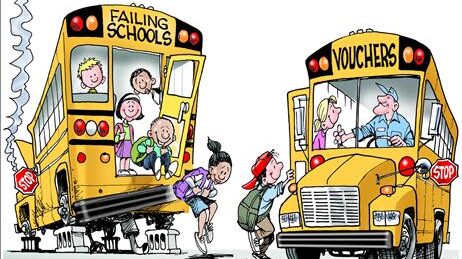

Fortunately, economist Thomas Sowell (my colleague at the Hoover Institution) has offered a solution. In his new book, Charter Schools and Their Enemies, he shows that schools with more autonomy and flexibility than traditional public schools are closing the educational divide, providing sorely needed choice, opportunity, and competition.

Sowell’s careful analysis of the data, which was available before the pandemic struck, shows that students in publicly funded but privately operated charter schools like Success Academy in New York City score remarkably higher on standardized achievement tests than do those in traditional public schools. The book contains reams of convincing evidence, all of which is explained beautifully and presented clearly in more than 90 pages of tables.

Sowell controls for many factors, including school location: students at charter schools within the same building as a traditional public school perform several times better on the same tests. And he supplements the hard data with simple evidence, such as the long waiting lists to get into the better performing charter schools. But if charter schools work so well, what explains the enemies mentioned in the book’s title? Critics of charter schools would list many reasons, but the main one, Sowell laments, is that public schools simply do not want the competition.

Will the COVID-19 crisis finally change things? There are already positive signs that it has. Last month, US Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos unveiled a new, five-year $85 million scholarship fund that will help students from lower-income families in Washington, DC go to schools of their choice. It is part of her department’s Opportunity Scholarship Program, the only federally funded school-choice initiative in the United States. The average income of families in the program is less than $27,000 per year, and more than 90% of students in it are African-American or Hispanic/Latino.

In another promising sign, US Senators Tim Scott of South Carolina and Lamar Alexander of Tennessee recently introduced a bill to direct some of the educational relief funding in this year’s US Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to school-choice programs. That money would enable lower-income families that are hard-pressed by the pandemic to send their children to alternative schools. Among other things, the legislation would direct 10% of CARES Act educational funds toward scholarships for private-school tuition or reimbursement for homeschooling costs.

But most telling, perhaps, is the fact that many families and individuals are coming up with their own solutions. Consider the sudden blossoming of pandemic learning “pods,” wherein parents get together, find teachers, and form a class for kids in the neighborhood. Learning pods are a natural civil-society response to school closing in many districts in California and elsewhere. When schools suspend services, parents immediately will seek out alternative solutions, especially when they have concerns about their children’s ability to learn remotely.

Of course, learning pods already have enemies of their own, with critics complaining that the practice is unfair, harmful for traditional schools, or available only to those who can afford to hire teachers. But that is all the more reason to make high-quality, effective schools more widely accessible. Quashing new ideas is not the answer.

The struggle over pandemic-era education is quickly moving to statehouses. In June, as part of the new state budget, California lawmakers passed Senate Bill 98, which caps per-student state funding for charter and public schools at last year’s funding levels. The point is to limit charter school enrollments at a time when demand for alternatives to traditional public schools is surging. But with those public schools closing and resorting to remote teaching, students from lower-income households will be the ultimate victims.Sign up for our weekly newsletter, PS on Sunday

There are already at least 13,000 students waiting to enroll in charter schools in California. But owing to SB98, notes State Senator Melissa Melendez, “if you are in a school that is failing that is really too bad. You are just going to have to stay there and deal with it. That is not fair to the student or the parent.”

In his book, Sowell points out that, “Those who want to see quality education remain available to low-income minority neighborhoods must raise the question, again and again, when various policies and practices are proposed: ‘How is this going to affect the education of children?’”

If we all focus squarely on that question, the pandemic’s long-term impact on education could turn out to be highly beneficial.