First they warned of global warming, and when they needed a new narrative “global warming” became “climate change.” They finally settled on something they could prove because the climate does, in fact, change. First it rains, and then the sun comes out. Then it rains again. Rain, sun, rain, sun, drip, drip and dry. The narrative is ever new.

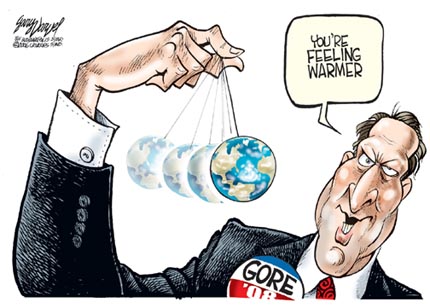

There was always a scarcity of evidence that the globe was on a wild tear, but there was never a scarcity of alarm. We got bedtime stories of ghosts and goblins from the graveyard, wild monsters from Boggy Creek, even a creature from a black lagoon and all kinds of other things that make the night a time of fearsome fun and games. Al Gore, who had a lot of time on his hands after his White House gig was aborted, even made a movie about it. It’s still popular in certain circles on Halloween night.

Only 13 years ago (and 13 is the unluckiest of the numbers, which is pretty scary, too), a scientist at the climate-research unit of Britain’s University of East Anglia predicted that “within a few years’ time” a snowfall would be “a vary rare and exciting event. Children just aren’t going to know what snow is.” Some of the newspapers eagerly cooperated with spreading the “news.” One of them reported that for the first time a well-known toy shop on London’s Regent Street had no sleds on display. Who needs scientific evidence when you have a story like that?

That was then, and this is now, and Britain is huddled against predictions that 2013-14 will be one of the coldest and wettest winters in a very long time. “Worst winter for decades,” cried the Daily Express. “Record-breaking snow predicted for November.” And so it came to pass. By the end of November, British teeth were chattering, and snow, ice and plummeting temperatures were at hand all across “the sceptr’d isle,” and it wasn’t yet winter. The kids were getting lots of lessons in “snow,” the snow they were never going to see.

The global-warming hysteria grew quickly after that early prediction of a scarcity of snow. Certain scientists with more ambition than sense saw opportunity lying close at hand. With the falling snow could come falling grants to pay for learned papers. Learned academics have learned that a feverish alarm, served with a dollop of hysteria, can move the learned nonsense out of the faculty lounge and into the newspapers and onto television screens. And not just in Old Blighty, whence the scam originated.

James Hansen, whose career at NASA gave him the credentials to be taken seriously even when he didn’t sound serious, predicted that in the decade after 2020 the average annual temperature would rise by 9 degrees, with more heat to come. Soon we would be boiling like lobsters. An ambitious young man with his sights on medicine or the law might set his sights higher, and consider a career in fans and air conditioning.

Mr. Hansen, in an op-ed essay in The Washington Post, blames everything on “climate change” — the European heat wave of 2003, the Russian heat wave of 2010, catastrophic droughts in Texas and Oklahoma last year. To discount his view of what’s at stake — a climactic version of hope and change — “would be like quitting your job and playing the lottery every morning to pay the bills.”

The admiration Mr. Hansen and his like-minded colleagues have for themselves is as breathtaking as their contempt for all who disagree with them. The more their scam crumbles, the louder they shout its particulars. Mr. Hansen says he started speaking out about climate change again, after a period of relative reticence, because he did not want his grandchildren to say, “Pa, you understood what was happening, but you never made it clear.” Now that events are making it clear what a scam global warming really is, those grandchildren are more likely to say, “Pa, why did you tell all those fibs and stretchers for so long?”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Wesley Pruden is editor emeritus of The Washington Times.