There were numerous oddball characters in “M.A.S.H.,” the old TV show about a surgical hospital in the battlefront in Korea. One of them, Major Winchester, considered himself the consummate practitioner. In one episode, he droned continually, “I do one thing. I do it very well…and then I move on.”

That fairly describes how President Obama would have described his approach to foreign policy before Tuesday night’s speech.

He personally handled every serious issue. He decided on his time table. He delivered a prepared address explaining how he had solved each conundrum. And then he moved on.

That was the gist of his address this May at the National Defense University, where he confidently explained how his policies had left Al Qaeda all but eradicated. He made similar speeches on Iraq, Afghanistan, Egypt, and Libya.

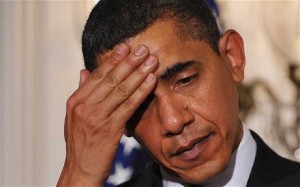

That was not the Barack Obama America saw Tuesday night. This was a foreign policy speech unlike any other from the president.

In the “M.A.S.H.” episode mentioned above, the surgery is suddenly flooded with casualties. Major Winchester is completely overwhelmed. A fellow surgeon leans over and says, “Just deal with it. It’s all meatball surgery.”

For the first time in his presidency, Obama finds himself practicing meatball foreign policy—reacting to events, forced to address issues on a timetable set by others, and made to take steps before he has time to think them through methodically.

Mr. Obama never planned to get dragged into the Syrian civil war. He uttered his “red line” declaration only because it sounded strong and had been advised that, in all likelihood, he would never have to enforce it. But when the line was publicly crossed, suddenly, the White House felt unavoidable pressure to act.

It opted for Libya-lite—an all-air-based assault, without the regime change. The president would strike while Congress was out of town, and then explain his actions to the American people. But Britain bailed, and that plan went south.

Rather than “go it alone,” the president switched to a new plan: try to get a balky Congress to green-light use of force—even though he (rightly) insisted he didn’t need their approval. Tonight’s speech was slated with the intent of winning over Congress and the American public to his intervention plan.

But before that speech could be delivered, Russia unexpectedly stepped in and offered a “diplomatic” solution that made a unilateral strike—no matter how down-sized from the Libyan adventure—appear untenable.

And so Obama found himself making a very different televised address—one that pretty much admitted that he had no choice but to follow Russia’s lead.

The 16-minute speech failed on every level. Mr. Obama didn’t explain why he is now endorsing a “solution” that actually makes Syrian strongman Bashar Assad even stronger. What keeps Assad in power is not his chemical weapons but the support he gets from Russia, Iran and Hezbollah. And Russia’s diplomatic ploy strengthens Moscow’s ability to support the regime.

In addition, it gives Damascus completely unearned respectability. Assad can claim he is cooperating with the international community. In many ways, this may be a worse outcome than a meaningless military strike. An approach that strengthens Assad may lengthen the bloody civil war that has already claimed 100,000 lives and created 2 million refugees.

The speech also failed to give Congress any reason to endorse an attack if diplomacy fails. The president asked Congress to postpone the vote because he doesn’t have the votes. If the Syrian situation deteriorates further, Congress will be even less likely to give the President a formal authorization to use military force.

The speech was, however, historically significant, as it marked the collapse of the Obama Doctrine. As a candidate and as a president, Barack Obama approached foreign relations with one key belief: If he made nice with the world, the world would make nice with him.

That naïve view has now been trampled by harsh reality. America’s enemies have found they can play our president. Moscow may be the first capital to recognize that Mr. Obama is off his game, but it will not be the last.

And so, like Major Winchester, Mr. Obama now finds himself doing what he wanted least to do: meatball surgery. In the case of Syria policy, put a fork in the meatball. Its done.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

James Jay Carafano is vice president of foreign and defense policy studies at The Heritage Foundation. This article was published at FoxNews.com.