Poor Syria. Strategically located at the northern edge of the Middle East on the shore of the Mediterranean Sea, with its archeological finds dating back nearly eight thousand years, is perhaps the oldest continually inhabited place of the world. Its two most important cities Aleppo and Damascus had been the capitals of numerous empires dating back at least to the thirtieth century BC. Throughout its history, ancient Syria was blessed with productive agriculture, profitable trade as well as thriving urbanized culture that created religions and philosophies, and invented the very first alphabet. On the other hand, ancient and modern Syria had been also cursed and shaped by never ending cycles of religious and sectarian violence.

The roots of the civil war that started in the beginning of 2011 go back to the mid-9th century when Ibn Nusayr declared himself the “Bab” – the “gateway to truth.” Proclaiming his teachings to be the only true religion, Ibn Nusayr preached the Holy Trinity of Muhammad, his cousin and son in law Husayn ibn Ali, and Salman al-Farisi, a freed Persian slave of Muhammad’s. Ali was also elevated to be the Jesus-like incarnation of divinity. Borrowing further from Christianity, he made the symbolic presentation of bread and wine an integral part of religious services, in which wine represents God himself. Moreover, the Nusayris, also called Alawis or Ansaris, celebrate almost all Christian festivals and holidays, and worship most of the Christian saints. Finally, Ibn Nusayr denied the five pillars of Islam and rejected the Shari’a in its entirety.

Such heretic deviations from Sunni and Shi’a Islam earned the Nusayris/Alawis/Ansaris in the 14th century a fatwa from the Syrian religious and legal scholar Ibn Taymiyyah, in which he branded them “more heretical than the Jews and the Christians, even more so than many polytheists.” Thus historically, the religious community that began to call itself Alawis was not only excluded from Islam by the Sunni as well as the Shi’a communities but hated and persecuted by both with equal brutality. In turn, the Alawis were frightened of the Sunnis and the Shi’a alike and, consequently, hated both. Mutually entrenched in hatred and fear, each appeared to the other as a mortal enemy that must be crushed decisively.

Indeed, throughout their troubled and bloody historical coexistence, lay an ever present fear and sense of existential vulnerability. As a result, Syria became the quintessential battleground not only of religious and sectarian warfare, and zero-sum political conflicts for absolute power, but of terrorism and religion-based ideological fanaticism too. Chronologically, Syria’s history seemed to progress linearly but, in reality regressed circuitously. The Sunni majority ruled and the Alawi minority was ruthlessly repressed. The fortunes of the two opposing religious communities started to change after World War I, when the French enlisted the Alawis to control the majority Sunni population. A brief reversal occurred between 1946 and 1963, when independence from the French mandate restored the Sunnis to power. The situation changed again, when the Ba’ath coup d’etat elevated the army to power. Having disposed of his only rival, Salah Jadid, who led the coup d’etat, the Alawi General Hafez ibn Ali ibn Sulayman al-Assad seized power in 1971. Sunni revolts and uprisings under the leadership of the Muslim Brotherhood against Assad’s usurpation of power followed in fairly regular intervals. Equally, on a regular basis, these attempts at restoring Sunni dominance were brutally crushed by Syria’s Alawi dominated military.

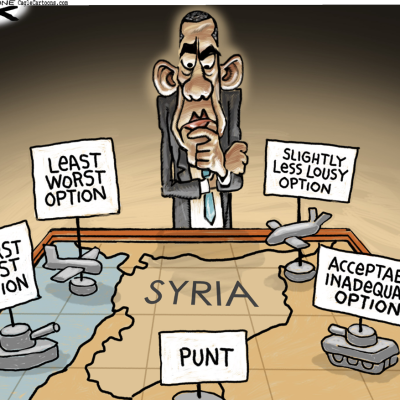

However brutal the Assad regime has been, mere repression can win battles but cannot win the enduring war, in which existential interests are involved. For these reasons, no amount of military might or foreign intervention on behalf of Hafez Assad’s son Bashar would bring peace and stability that could endure under the current political arrangements for Syria. Limitless violence attracts limitless counter-violence. The anti-Assad regime forces have started to wage war which disregarded all the rules. The Assad regime has answered in kind. More recently, Iran, Russia, and to a lesser extent Turkey, have foolishly believed that by intervening and defeating militarily the various opposition militias to the Assad regime they could restore the status quo ante.

The fall of Aleppo will not end the civil war, because at present there are three diametrically opposed parties in Syria. First, there are those who are willing to do what the Iranians and the Russians tell them. This party comprises less than ten percent of the population of Syria. Second, those who desire peace, stability, and freedom. This party encompasses the majority of Syrians who are overwhelmingly pro-Western and pro-democracy. Third, those who are enemies of Shi’a Iran, Russia, and Turkey. This third party contains also the majority of the Syrians. The Assad regime and its Iranian and Russian overlords support the first, offer empty promises to the second, and represses the third.

The ninety percent that are in passive or active opposition to the regime are also divided into three parties. To the first belong those who desire to restore the pre-Assad era. The second party want to see the Assad regime, its supporters, and the various militias to disappear, and establish a constitutional republic. Finally, the third party strives to build a Salafist Sunni state, closely allied with the monarchies of the Gulf and the Arabian Peninsula.

The Assad regime has been put in chains by Iran and Russia. Iran and Russia exist in a quagmire, because occupation does not amount to conquest. Syria will continue to face bloody chaos and hopeless instability. Meanwhile, innocent people will continue to die and the rest of the world will profess meaningless solidarity amidst the cavalcade of genocide, and regional jockeying.