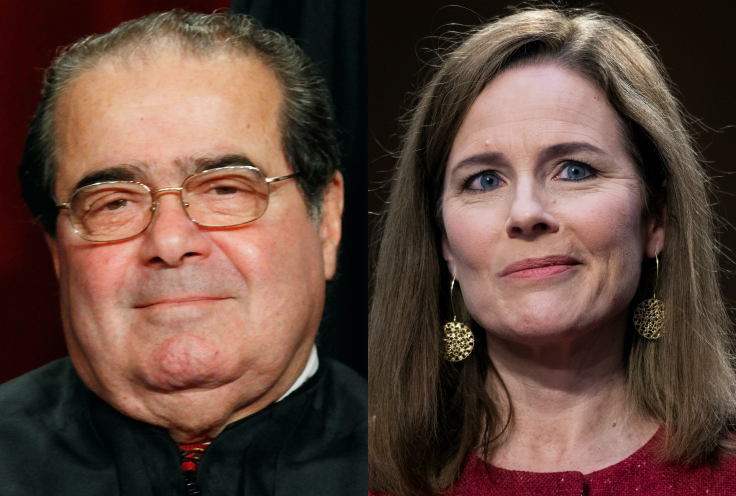

“Enough to field a baseball team.” That was the late Justice Antonin Scalia’s response when asked how many children he had. And he and his wife Maureen’s nine children have themselves parented, as of this week, 40 grandchildren. How big is the Scalia family? So big that, at the moment, it would not be allowed to hold an in-person gathering in the justice’s home state of New Jersey.

Even that count might not be accurate. Watching Judge Amy Coney Barrett testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee this week, I couldn’t help thinking that the Scalia family is larger than the individuals directly related to him. In both her September 26 remarks at the White House and her October 12 opening statement to the committee, Barrett spoke of the influence Scalia had on her life and identified herself with his approach to the law. “His judicial philosophy was straightforward: A judge must apply the law as written, not as the judge wishes it were,” Barrett told the senators. “Sometimes that approach meant reaching results that he did not like. But as he put it in one of his best-known opinions, that is what it means to say we have a government of laws, not men.”

Whether it was for the students he taught, or the clerks he hired, or the lawyers he mentored, or the readers of his work, Scalia modeled a form of jurisprudence rooted in the text of the Constitution and in the American political tradition. His approach came to be called originalism (in matters of constitutional interpretation) and textualism (in matters of statutory interpretation). But his legacy is far greater than these contributions to legal terminology and methodology. What this son of an Italian immigrant accomplished was nothing less than a revolution in the law—and the promulgation of a distinctly American conservatism that is needed now more than ever.

It was Scalia who was among the first faculty advisers of the Federalist Society, and who addressed the society’s first national gathering in 1982. Along with his colleagues Robert Bork and Laurence Silberman, Scalia stood for the idea that judges should interpret the Constitution and statutes based on their original public meaning. The clarity of his argument, the force of his intellect, and the charm of his conversation enlarged the audience for his views. That audience exploded in size after President Reagan elevated him to the Supreme Court in 1986. Over time, the strength of originalism’s reputation in legal circles became so overpowering that some liberal judges, such as Justice Elena Kagan, felt it necessary to describe themselves, however ironically, as “originalists.”

Scalia pointed to his decision upholding the constitutionality of flag-burning as proof that originalism is not a mask for conservative politics. And there have been plenty of decisions—most recently Justice Neil Gorsuch’s opinion in Bostock—where self-described originalists and textualists arrived at places conservatives did not expect. But there is nonetheless an integral relationship between originalism and conservatism. What American conservatism seeks to preserve is the institutional and philosophical inheritance of the American Founding. This inheritance is codified in our enabling documents: the Constitution (as amended), the organic laws of the United States (which include the Declaration of Independence and the Northwest Ordinance), and the Federalist Papers. It is through fidelity to these words, as the Founders understood them at the time, that conservatives defend the constitutional structure and the individual freedom it secures.

Originalism has turned out to be more than a legal doctrine. It is the common ground of American conservatism. For years, the right has tried to define a “constitutional conservatism” that would serve as the political analogue to originalism. That project has been overshadowed by the rise of national populism. But it is worth noting that the current president won his office in no small part because he pledged to nominate judges in the mold of Scalia and approved by the Federalist Society. And his most enduring legacy will be his appointments to the federal courts.

It would be difficult to name other Supreme Court justices who have had such a galvanizing effect on American politics—and who continued to play such important roles after their deaths. What accounts for Scalia’s iconic stature? The latest collection of his writings, The Essential Scalia, edited by Judge Jeffrey S. Sutton and Edward Whelan, offers some clues. “Nino loved ideas—thinking about them, talking about them, arguing about them, as well as writing about them,” Justice Kagan writes in her introduction. “That love may explain why he found it so natural to befriend colleagues with whom he often disagreed (yes, like me).” Scalia’s ability to depersonalize intellectual debate was a function of his self-confidence and sense of humor. His convictions were the result of deep reflection. But he was more than happy to defend them, and to explain why you were wrong.

What comes across most, though, is the quality of Scalia’s writing. It is clear, direct, witty, lapidary, memorable. Scalia’s opinions and dissents are famous for certain lines—”this wolf comes as a wolf”; “What Is Golf?”—but on second reading it is the way he develops his argument that most impresses. And he always makes a perfect landing. “Undoubtedly some think that the Second Amendment is outmoded in a society where our standing army is the pride of our Nation, where well-trained police forces provide personal security, and where gun violence is a serious problem,” he wrote in Heller (2008). “That is perhaps debatable, but what is not debatable is that it is not the role of this Court to pronounce the Second Amendment extinct.”

These aren’t judicial decisions. They are essays. And like great literature they will reverberate far into the future. As Antonin Scalia’s extended family, biological and philosophical, continues to grow.