In early 2011, the Senate Judiciary Committee held a hearing on the constitutionality of ObamaCare (né the Affordable Care Act of 2009). One would think that the time for such a hearing might be before passage of the act, but that is the way we do things around here, and besides, that is not the point of this column, which (as you can see from the title), is about the minimum wage.

The point derives from an exchange between Utah’s freshman (very fresh at the time, only a day or two old) Senator Mike Lee and Walter Dellinger, heavyweight lawyer, professor of constitutional law at Duke University, Assistant Solicitor General, presidential legal adviser, and then Acting Solicitor General in the Clinton Administration. In the course of the exchange, Lee wondered why, if the Interstate Commerce Clause would support a requirement for everyone to buy insurance, it wouldn’t support a requirement that every citizen buy (if not actually consume) three servings of leafy green vegetables every day. (That was in the heady days when supporters of ObamaCare still thought it was a regulation, before Chief Justice Roberts discovered that it was actually a tax.)

In response, General Dellinger (they do actually call them that) said that such a requirement would be a bridge too far, and therefore unconstitutional. In analogy, he animadverted (I can’t use a word like that in today’s college classroom, so I have to do it here) to the minimum wage. He claimed that, while Congress can constitutionally impose a minimum wage, it has never imposed a $5,000 minimum wage, and so such a minimum wage would be unconstitutional. (Was Dellinger hinting at the level that liberals truly want? I fear we may find out.)

This reasoning is, if I may say so, unreasonable, bereft as it is of any kind of principled rationale by which one might know whether one’s actions were going to be construed under the law as legal or illegal (a point that did not escape Senator Lee, though he did not have sufficient time to develop it). But since this kind of argument is often used (I use it myself) against the minimum wage, I’d like to explore its application in a bit more detail.

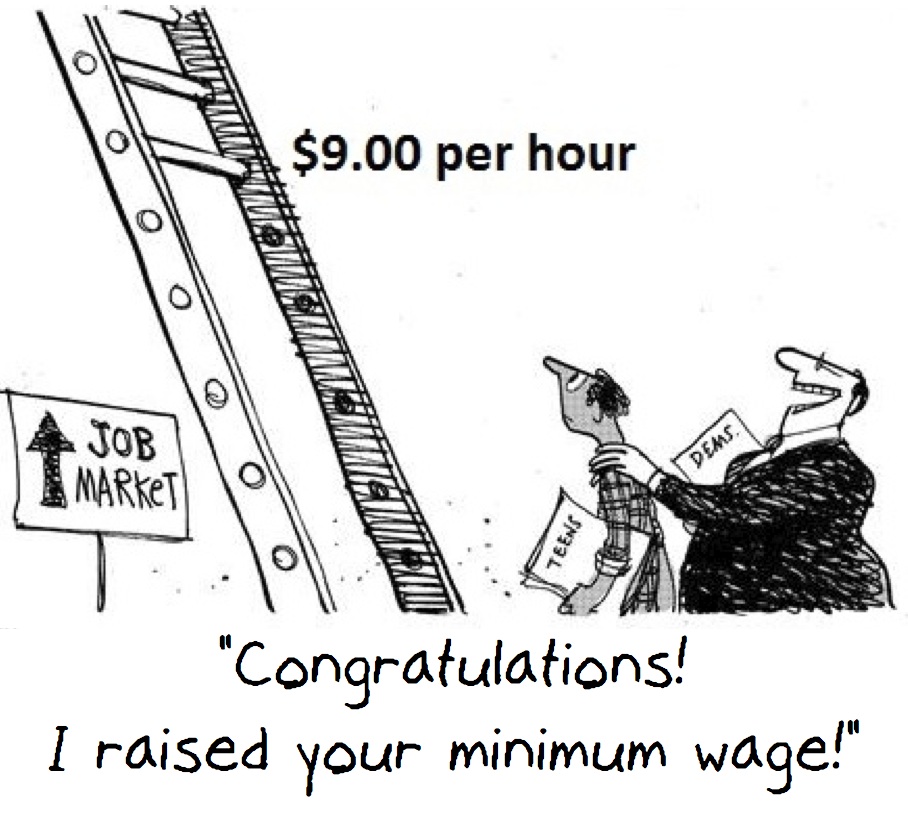

Stripped to its essence, this defense of the minimum wage amounts to the following proposition: everyone knows that a minimum wage of $100 an hour would have harmful effects on entry-level workers, but an increase to $9 from the current $7.25 will not. In other words, there is a “threshold effect” that works in wages.

It is true that this insight provides no guidance as to where the line lies between a harmless “little” increase and harmful “large” one. It is also true that liberals will not allow use of a “threshold effect” in other areas, say water pollution. Dioxins are bad, they tell us, and they are bad at any level. There is no “safe” (and therefore tolerable) level of dioxin contamination that can be allowed.

But apparently there is a threshold effect for wage increases; a little increase will do only good; a huge increase would do harm.

If we follow the enviros, and reject the threshold, who will suffer the harm?

Inevitably, it will be those least prepared to compete for the higher wage, those just entering the workforce, and, inevitably, those effects will fall most severely on black teenagers, who already suffer unemployment rates approaching 40%.

This effect was intentional for some of those proposing the first minimum wage (and its functional equivalent, the Davis-Bacon Act) back in the 1930s. Numerous commentators have noted the irony of a black president proposing to increase black unemployment. Unfortunately, one of them was not Marco Rubio (or Rand Paul for that matter). Well before delivery of the State of the Union message, it was widely reported that President Obama was going to call for an increase in the minimum wage. Rubio had to have known. That he did not forcefully point out the consequences of this proposal may be an early signal that he will be as inept a communicator in 2016 of the real world effects of Obamanomics as Mitt Romney was in 2012.

How hard would it have been to cite Representative John Cochran (D-Mo.) in 1931, to the effect that he had “received numerous complaints in recent months about Southern contractors employing low-paid colored mechanics”? Or Rep. Clayton Allgood (D-Ala.) worried about his contractor constituents having to cope with “cheap colored labor . . . of the sort that is in competition with white labor throughout the country”?

Big Labor was complicit then as it is now. The AFL’s president William Green complained that “[C]olored labor is being sought to demoralize [lower] wage rates.” A mandated minimum above the market level would, he noted, prevent competition by black workers. It was at that moment that unemployment rates for blacks and whites begin to diverge. Until then there had been little difference.

These days, unions support increases in the minimum wage because many of them, particularly in the retail, service and hospitality industries tie their base wage rates to the minimum wage, so that they increase whenever the minimum is increased, either by a direct differential or by a re-opening of labor agreements.

It would be unfair to ascribe racist motives to all supporters of David-Bacon, “prevailing-wage” legislation, and the minimum wage. No doubt some of those voting for it genuinely believed, against all logic, and despite the explicit arguments made by the sponsors, that it would provide economic benefits for those at the lowest levels of the economic ladder. We shouldn’t expect our elected representatives to be especially clear thinkers, and they did not have the benefit of years of experience with a minimum wage, as we do.

But even when they did, the insensitivity of many northern “liberals” to the real-world effect is startling. Thus such a quintessentially bleeding heart as Sen. Jacob Javits (R-NY), in a hearing as late as 1957, could defend the northern-state industrial white worker from “unfair” competition from the cheaper “colored worker” from the south by supporting minimum wage increases.

At that hearing, Clarence Mitchell of the NAACP showed his understanding of what was going on, but I don’t recall that it ever cost Javits the endorsement of that organization.

But Javits’ blindness (or callousness) is as nothing compared with the cynicism of former Democratic presidential candidate Michael Dukakis, who (along with Daniel Mitchell of UCLA) argued in the New York Times in 2006 that a high minimum wage would destroy the jobs being filled by illegal immigrants. “[I]t makes sense” they wrote “to reduce the abundance of extremely low-paying jobs that fuels [illegal immigration]. If we raise the minimum wage, it’s possible some low-end jobs may be lost; but more Americans would also be willing to work in such jobs, thereby denying them to people who aren’t supposed to be here in the first place…. If Congress would only remove its blinders about the minimum wage, it may see a plan to deal effectively with illegal immigration, too.”

How those jobs could be destroyed without increasing low-income (and especially black) unemployment is a little hard to see.

Finally, the president’s proposal to index the minimum wage permanently to counter the effects of inflation is one more bone-headed idea. Government hardly needs more incentives to inflate the currency. This idea would not only penalize those just starting out in the job market, by removing the jobs they are economically qualified to fill. It would also penalize those at the other end of the career arc, the retired living on fixed incomes. They would see the value of their pensions and investments eroded by the hidden tax of inflation.

Apparently we dodged a bullet when Candidate Dukakis went down in flames; Barack Obama’s economic ignorance seems to exceed that of Dukakis, and the target is now squarely on our chests.

– – – – – – – – – –

Gordon S. Jones is a senior fellow at Frontiers of Freedom. Jones is also an adjunct professor at Utah Valley University and Salt Lake Community College. Jones has extensive experience in Congress, in public policy, and elective politics.