At a political event in Wilmington, Delaware, on Thursday, President Obama devoted only 40 seconds to the shooting down of the Malaysian airline, his first statement to the world following the news.

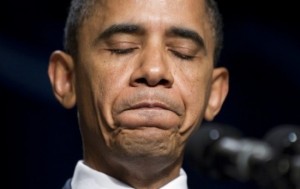

His emotionless reference to the attack as ‘a terrible tragedy’ seemed disconnected from the horrific moment, particularly as he immediately reverted to script to praise his administration and criticise Republicans.

It was a far cry from President Reagan’s 1983 fierce denunciation of the Soviet shooting down of a Korean airliner as a ‘crime against humanity’.

But it only confirmed the chaos into which US foreign policy has descended since the summer of 2012 when reporters at a White House briefing asked Mr Obama about the security of chemical weapons in the Syrian stockpile.

The commander in chief went beyond safety and said: ‘We have been very clear to the Assad regime … that a red line for us is [when] we start seeing a whole bunch of chemical weapons moving around or being utilised.’

The term ‘red line’ is the kind of clear, emphatic language major powers use only when they are prepared to back words with action.

A little over a year later, the Assad regime utilised chemical weapons against its own people.

The number of blunders that the President and his administration committed in the ‘red line’ affair is hard to fathom.

Before the President spoke, no one vetted the term and its consequences in the White House policy process and, once the words came out, no one undertook preparations in case Syrian president Bashar al-Assad called Mr Obama’s bluff.

According to reports, no one made the diplomatic rounds to line up the support of allies just in case, or the congressional rounds to line up the support of Congress. No one developed military plans or sent quiet signals to Assad that the US was not to be trifled with on this matter.

These actions are routine when any White House makes as definitive a commitment as the President made, except, apparently, this White House.

Even bigger blunders came after the Syrian chemical attack. Mr Obama began signalling that, despite his remark, he did not want a response, any response. First there was the verification charade. Multiple eyewitness accounts of rockets rising out of Syrian army installations and falling into the stricken zones at the time of the chemical attacks were not enough to warrant quick action.

Then there was his call for a congressional vote, delivered just when the need to respond was most urgent if air strikes were to deliver an effective message.

Finally, there was the utter failure to attract congressional support, assuming Mr Obama really wanted Congress to endorse the proposed attacks.

That the Parliament of our closest ally, Great Britain, rejected an air campaign first gave Mr Obama an additional reason for inactivity. The flailing seemed to end when Russian President Vladimir Putin opened the door to a negotiated deal with Syria. But it was not the end; it was the beginning.

For as the administration rushed to that door, all over the world those who depended on America when in harrowing circumstances were asking themselves: How reliable is America now? How strong now?

Also asking was Mr Putin. He noted the contrast between Mr Obama’s bold talk and timid response. As the former head of a friendly government said in a small meeting I attended not long ago: ‘Putin is cautious. He will probe. If he encounters resistance, he will pull back.’

The US failure to follow through in Syria gave the Russian president confidence that he could move with impunity.

Soon he was picking a fight with Ukraine. Like the scene in The Godfather – when, at his child’s baptism, Michael Corleone renounces the devil as the camera cuts back and forth to his men eliminating rival gangsters – Putin, before global television cameras, watched the opening ceremonies of the Sochi Olympics as Russian troops began movements preparatory to seizing Crimea.

This week, in the skies over Ukraine, we saw the consequences of the recklessness that the Russian godfather’s probing has unleashed.

Putin was not the only one to detect opportunity in American indecision. China stepped up its probes in the East and South China Seas. In the Middle East, with the US military presence drawn down nearly to zero in Iraq and soon Afghanistan, an army of ruthless fanatics gestating unnoticed in Syria’s east saw the chance to break out of national boundaries and within a few weeks occupied much of western and central Iraq.

Why has so much of the global order come apart so fast?

For the same reason that, as a friend reports, on the streets of San Salvador those who will smuggle your child to the Rio Grande have been securing an unprecedented volume of sign-ups. When asked about the chances of the child staying in America once the border is crossed, they tell parents: ‘It has never been easier.’

Now the word on weakness is everywhere, even the poorest barrios of Central America.

‘The fact that you have a crisis in Ukraine has nothing to do with Gaza,’ a deputy national security adviser to the President told an interviewer recently.

The current White House doesn’t understand how US fecklessness in Syria can reverberate to Ukraine, and from there to the South China Sea, and the Americas, and Gaza and elsewhere in the Middle East.

In all this I have referred to the United States as the primary shaper of world events, which is, in fact, a misleading shorthand. The US is not a superpower so much as the biggest player in a set of super-alliances, the most critical of which is with the UK.

Since the Second World War, when the US and Britain have been of one mind, liberal values have been secure and even advanced. When either has lost its sense of direction, neither has been nearly so effective.

The great danger in being the anchor to the global order is that when we lose our way the general peace itself is threatened.

This is just what we are seeing in theatre after theatre around the world. Perhaps it is time for a key ally like Prime Minister David Cameron to have a friendly talk with the President.

It is not just American interests that a flailing White House threatens. It is that of peoples everywhere.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Clark S. Judge is founder and managing director of the White House Writers Group, Inc. and an opinion journalist. This article was originally published in the London Mail.