At the Paris conference, expect an agreement that is sufficiently vague and noncommittal for all countries to claim victory.

By Matt Ridley and Benny Peiser • Wall Street Journal

By Matt Ridley and Benny Peiser • Wall Street Journal

In February President Obama said, a little carelessly, that climate change is a greater threat than terrorism. Next week he will be in Paris, a city terrorized yet again by mass murderers, for a summit with other world leaders on climate change, not terrorism. What precisely makes these world leaders so convinced that climate change is a more urgent and massive threat than the incessant rampages of Islamist violence?

It cannot be what is happening to world temperatures, because they have gone up only very slowly, less than half as fast as the scientific consensus predicted in 1990 when the global-warming scare began in earnest. Even with this year’s El Niño-boosted warmth threatening to break records, the world is barely half a degree Celsius (0.9 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than it was about 35 years ago. Also, it is increasingly clear that the planet was significantly warmer than today several times during the past 10,000 years.

Nor can it be the consequences of this recent slight temperature increase that worries world leaders. On a global scale, as scientists keep confirming, there has been no increase in frequency or intensity of storms, floods or droughts, while deaths attributed to such natural disasters have never been fewer, thanks to modern technology and infrastructure. Arctic sea ice has recently melted more in summer than it used to in the 1980s, but Antarctic sea ice has increased, and Antarctica is gaining land-based ice, according to a new study by NASA scientists published in the Journal of Glaciology. Sea level continues its centuries-long slow rise—about a foot a century—with no sign of recent acceleration.

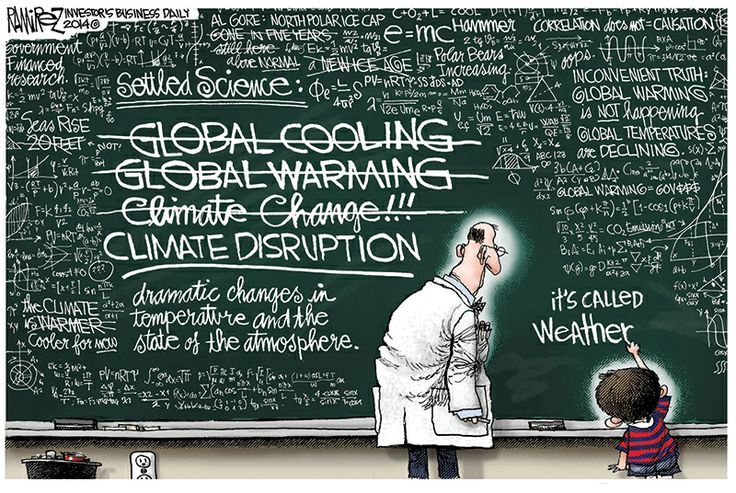

Perhaps it is the predictions that worry the world leaders. Here, we are often told by journalists that the science is “settled” and there is no debate. But scientists disagree: They say there is great uncertainty, and they reflected this uncertainty in their fifth and latest assessment for the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). It projects that temperatures are likely to be anything from 1.5 to 4.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 to 8.1 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer by the latter part of the century—that is, anything from mildly beneficial to significantly harmful.

As for the impact of that future warming, a new study by a leading climate economist, Richard Tol of the University of Sussex, concludes that warming may well bring gains, because carbon dioxide causes crops and wild ecosystems to grow greener and more drought-resistant. In the long run, the negatives may outweigh these benefits, says Mr. Tol, but “the impact of climate change does not significantly deviate from zero until 3.5°C warming.”

Mr. Tol’s study summarizes the effect we are to expect during this century: “The welfare change caused by climate change is equivalent to the welfare change caused by an income change of a few percent. That is, a century of climate change is about as good/bad for welfare as a year of economic growth. Statements that climate change is the biggest problem of humankind are unfounded: We can readily think of bigger problems.” No justification for prioritizing climate change over terrorism there.

The latest science on the “sensitivity” of the world’s temperature to a doubling of carbon-dioxide levels (from 0.03% of the air to 0.06%) is also reassuring. Several recent peer-reviewed studies of climate sensitivity based on actual observations, including one published in 2013 in Nature Geoscience with 14 mainstream IPCC authors, conclude that this key measure is much lower—about 30%-50% lower—than the climate models are generally assuming.

A key study published in the Journal of Climate this year by Bjorn Stevens of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Hamburg, Germany, found that the cooling impact of sulfate emissions has held back global warming less than thought till now, again implying less sensitivity. So the high end of the IPCC range is looking even more implausible in theory and practice. When politicians intone that, despite the slow warming so far, “two degrees” of warming is inevitable and imminent, remember they are using high estimates of climate sensitivity.

Yes, but if there is even a tiny chance of catastrophe, should the world not strain every sinew to head it off? Better to decarbonize the world economy and find it was unnecessary than to continue using fossil fuels and regret it. If decarbonization were easy, then sure, this would make sense. But the experience of the last three decades is that there is no energy technology remotely ready to take over from fossil fuels on the scale needed and at a price the public is willing to pay.

Solar power is cheaper than it was, but even if solar panels were free, the land, infrastructure, maintenance and backup power (for nighttime and cloudy days) would still make it more expensive than gas-fired electricity. Solar provides about 0.5% of the energy generated world-wide. Wind has expanded hugely, but at massive cost, yet still supplies a little more than 1% of all energy generated globally. Nuclear is in slow retreat, and its cost stubbornly refuses to fall. Technological breakthroughs in the production of gas and oil from shale have outpaced the development of low-carbon energy and made it even less competitive.

Meanwhile, there are a billion people with no grid electricity whose lives could be radically improved—and whose ability to cope with the effects of weather and climate change could be greatly enhanced—with the access to the concentrated power of coal, gas or oil that the rich world enjoys. Aid for such projects has already been constrained by Western institutions in the interest of not putting the climate at risk. So climate policy is hurting the poor.

To put it bluntly, climate change and its likely impact are proving slower and less harmful than we feared, while decarbonization of the economy is proving more painful and costly than we hoped. The mood in Paris will be one of furious pessimism among the well-funded NGOs that will attend the summit in large numbers: Decarbonization, on which they have set their hearts, is not happening, and they dare not mention the reassuring news from science lest it threaten their budgets.

Casting around for somebody to blame, they have fastened on foot-dragging fossil-fuel companies and those who make skeptical observations, however well-founded, about the likelihood of dangerous climate change. Scientific skeptics are now routinely censored, or threatened with prosecution. One recent survey by Rasmussen Reports shows that 27% of Democrats in the U.S. are in favor of prosecuting climate skeptics. This is the mentality of religious fanaticism, not scientific debate.

So what will emerge from Paris, when thousands of government officials gather from Nov. 30 to Dec. 11 to agree on a new U.N. climate deal to replace the Kyoto Protocol, which expires in 2020? Expect an agreement that is sufficiently vague and noncommittal for all countries to sign and claim victory. Such an agreement will also have to camouflage deep and unbridgeable divisions while ensuring that all countries are liberated from legally binding targets a la Kyoto.

The political climate is conducive to such an ineffectual agreement. Concerns about the economy, terrorism and international security have been overshadowing the climate agenda for years. The fact that global warming has slowed significantly over the past two decades has reduced public concern and political pressure in most countries. It has also given governments valuable time to kick painful decisions down the road.

The next 10-15 years will show whether the global-warming slowdown continues or whether a strong warming trend terminates the current pause for good. The Paris summit is likely to agree to a review process that reassesses global temperatures and carbon-dioxide emissions every five years. If the climate is less sensitive to carbon-dioxide emissions than climate models assume, the new accord should allow for the possibility of carbon-dioxide pledges to be relaxed in line with empirical observations and better scientific understanding.

Concerned about the loss of industrial competitiveness, the Obama administration is demanding an international transparency-and-review mechanism that can verify whether voluntary pledges are met by all countries. Developing countries, however, oppose any outside body reviewing their energy and industrial activities and carbon-dioxide emissions on the grounds that such efforts would violate their sovereignty.

They are also resisting attempts by the U.S. and the European Union to end the legal distinction (the so-called firewall) between developing and developed nations. China, India and the “Like-Minded Developing Countries” group are countering Western pressure by demanding a legally binding compensation package of $100 billion a year of dedicated climate funds, as promised by President Obama at the U.N. climate conference in Copenhagen in 2009.

However, developing nations are only too aware that the $100 billion per annum funding pledge is never going to materialize, not least because the U.S. Congress would never agree to such an astronomical wealth transfer. This failure to deliver is inevitable, but it will give developing nations the perfect excuse not to comply with their own national pledges.

Both India and China continue to build new coal-fired power stations. China’s coal consumption is growing at 2.6% a year, India’s at 5%, which is why coal was the fastest-growing fossil fuel last year. China has pledged to reduce energy and carbon intensity, but that is another way of saying it will increase energy efficiency—it doesn’t mean reducing use.

For the EU, on the other hand, a voluntary climate agreement would finally allow member states to abandon unilateral decarbonization policies that have seriously undermined Europe’s competitiveness. The EU has offered to cut carbon-dioxide emissions by 40% below the 1990 level by 2030. However, this pledge is conditional on all nations represented at the Paris summit adopting legally binding carbon-emissions targets similar to and as a carry-over of the Kyoto Protocol.

According to the EU’s key demand, the Paris Protocol must deliver “legally binding mitigation commitments that put the world on track toward achieving the below 2°C objective. . . . Mitigation commitments under the Protocol should be equally legally binding on all Parties.” The chances of such an agreement are close to zero. If there are no legally binding carbon targets agreed to in Paris, the EU will be unlikely to make its own conditional pledges legally binding.

Any climate agreement should be flexible enough so that voluntary pledges can be adjusted over the next couple of decades depending on what global temperatures do. The best we can hope for is a toothless agreement that will satisfy most governments yet allow them to pay lip-service to action. In all likelihood, that’s exactly what we can expect to get in Paris.

Mr. Ridley is a columnist for the Times (U.K.) and a member of the House of Lords; he has an interest in coal mining on his family’s land. Mr. Peiser is the director of the Global Warming Policy Forum.